22 Jump Street and the problem with comedy sequels

Based on a painfully dated police procedural remembered for launching Johnny Depp’s acting career and not much else, the first 21 Jump Street movie should have been a spectacular misfire, another cautionary tale about the dangers of exhuming a once-popular television series and hastily retooling it to attract modern audiences. Instead co-directors Phil Lord and Chris Miller delivered an inspired shot of lunacy that kick-started the pair’s reputation for salvaging projects other filmmakers would dismiss as long shots or lost causes, a reputation that was cemented in box office gold earlier this year with the spectacular success of The Lego Movie, which turned what could have been a soulless corporate cash-grab into a joyous, self-aware ode to playtime.

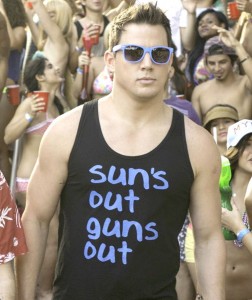

Undercover bros · Channing Tatum will return with Jonah Hill for 22 Jump Street, which finds the duo going undercover as college students. – Photo courtesy of Columbia Pictures

Thanks in large part to the almost vaudevillian chemistry between Jonah Hill and the unexpectedly hilarious Channing Tatum as Schmidt and Jenko, two undercover detectives frantically attempting to pass as jaded, ultra-hip high school students, 21 Jump Street was one of the biggest hits of spring 2012, ultimately grossing more than $200 million worldwide on a relatively conservative budget of $42 million. Given the critical and commercial reception of the film, a follow-up was inevitable. But can lightning be bottled twice?

Sequels, with their penchant for needlessly inflated budgets and paint-by-numbers plot repetition, are always a tricky business, but comedy sequels in particular tend to fare the worst in terms of being enjoyable, or even marginally tolerable. Will 22 Jump Street, scheduled for release this Friday, become one of the few to justify its own existence, or will it follow the path of mediocrity laid out by such forgettable flops as Caddyshack II, Blues Brothers 2000 and Airplane II: The Sequel?

So why is it so difficult to make a decent comedy sequel? For one thing, comedians are like sharks: they can’t stop moving forward or they’ll suffocate, and any attempt to play off old jokes and gags is bound to feel hackneyed in comparison to what’s come before. The Central Park brawl in last year’s Anchorman 2: The Legend Continues was packed to the rafters with clever imagery, instantly quotable dialogue and enough shameless celebrity cameos to make Jimmy Kimmel blush, but no amount of minotaur decapitations and soul-sucking Confederate generals could recapture the absurdist charm of the original Anchorman’s news team rumble.

Good comedy revels in the heady rush that comes from the discovery and exaltation of the new. After that all-important element of surprise is lost, it’s disturbingly easy to slide into stagnation. Bud Abbott and Lou Costello, arguably the funniest comedic duo of all time, were famously hesitant to add new routines to their repertoire, choosing instead to lean on well-worn classics such as “Who’s On First?” and this reluctance, coupled with the pair’s general overexposure and the rapid ascendance of Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis, hastened their decline in the early 1950s.

Nostalgia literally means “the pain from an old wound,” and comedies that rely on it too much run the risk of making their audiences suffer as well. With the exception of Michael Caine’s amorous, Dutch-hating gentleman spy, Austin Powers in Goldmember was just an extended reminder of how funny Mike Myers used to be, rehashing old running gags from International Man of Mystery and The Spy Who Shagged Me instead of inventing new ones.

In some cases, this misguided sense of nostalgia is transplanted from a completely unrelated movie. Be Cool, the belated but mostly bearable sequel to the showbiz send-up Get Shorty, caused quite a stir by promising to reunite John Travolta and Uma Thurman on the dance floor for the first time since the immortal twist contest scene in Pulp Fiction. The new dance, however, ended up being little more than a tepid, overproduced afterthought — the Black Eyed Peas are a piss-poor substitute for Chuck Berry — that contained none of the reckless abandon or sex-and-death ecstasy of the couple’s first onscreen encounter.

There’s a fine line between paying homage to previous films in a series and ripping them off wholesale. Some films — Todd Phillips’ The Hangover Part II and Jay Roach’s pointless threequel Little Fockers are particularly egregious examples — copy their predecessors beat-for-beat in ways so lazy and condescending that they could easily qualify as acts of self-plagiarism, offering up grotesque facsimiles of the original films where all the laughs have been replaced with cynical winks and sneers.

Not all comedy sequels have to be terrible. In fact, a chosen few — the second and third Toy Story films, National Lampoon’s Christmas Vacation — are rightfully regarded as genuine classics. They all have one thing in common: a willingness to push boundaries and expand their visions, even to the point of conceptual insanity. Back to the Future Part II, for example, embraced the first film’s time travel conceit with madcap zeal, resulting in a movie that darted in and out of the original’s timeline while taking the story and the characters — specifically the villainous Biff, who went from schoolyard bully to dystopian overlord thanks to an all-powerful sports almanac -— in bold new directions. The underrated Gremlins 2: The New Batch, meanwhile, took the first film’s monster movieformula and ran it through a paper shredder, evolving into what can only be described as an acid-soaked Chuck Jones cartoon, complete with an appearance from horror legend Christopher Lee as a resourceful mad scientist.

22 Jump Street, which finds Hill and Tatum posing as college freshmen in order to infiltrate a campus drug ring, appears to have a healthy amount of post-modern awareness about the low expectations associated with comedy sequels. Even its deliberately unimaginative title speaks to Lord and Miller’s amusement with the idea of unnecessary, studio-mandated follow-ups. The trailers, especially the profanity-laden red-band versions, are rife with jokes about formulaic storytelling, starting with the perpetually furious Captain Dickson (Ice Cube) and his oft-repeated catchphrase, “Do the same thing and everyone’s happy!” It’s that kind of insolent meta-commentary that makes Lord and Miller two of the most exciting, discreetly subversive filmmakers to hit the mainstream in quite some time. And just like the Jump Street boys, they’re used to working undercover.

Landon McDonald is a graduate student studying public relations. His column “The Reel Deal” runs Wednesdays.