Exploring identity: The value of representation within the Latinx label

A wide-eyed transfer student, Cherise Cayetano attended her first Latinx Student Assembly meeting at the Ronald Tutor Campus Center back in her sophomore year. The meeting started off with an icebreaker question: “Where are you from?”

“Just hearing that [question] I was like, ‘Oh, that’s because I’m here,’” said Cayetano, now a senior majoring in law, history and culture. “And then I remember we were doing the exercise and this guy looked at me. He was like, ‘Yeah, where are you from?’ like ‘Why are you here right now?’ And I was like, ‘Sir, my family is from Central America, please.’”

Cayetano is Garífuna, but if someone were to ask her what she identifies as, she’d say Black or Afro-Latina to appease the masses. For Cayetano, checking off the race and ethnicity boxes has not been an easy decision but rather one rooted in confusion and doubt. There has never been a box that has perfectly encompassed what it means to be Garífuna — the Afro-Indigenous people, culture and language of Central America.

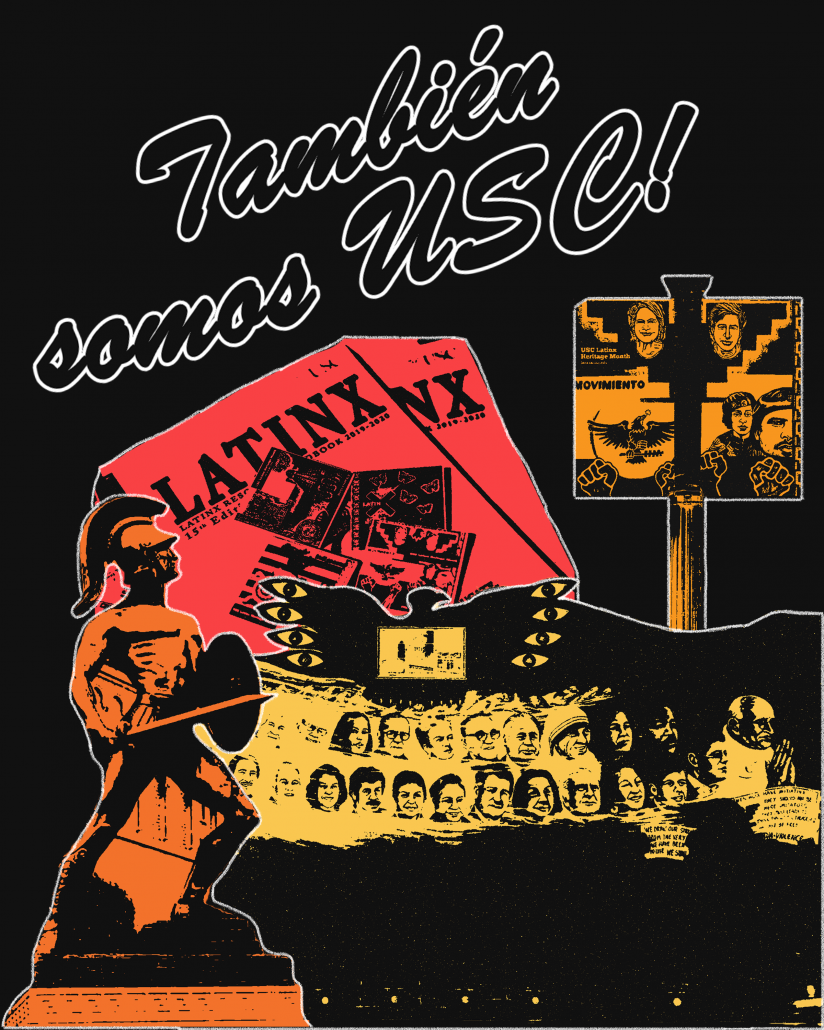

Racial identifiers used in these text boxes are ever-changing, and throughout decades, the search for a comprehensive, pan-ethnic term has evolved to meet global movements surrounding gender-inclusivity. While the terms Hispanic and Latino have been commonly used to describe those with Latin American or Spanish roots, resistance against these terms has resulted in the emergence of new identity markers, such as Latinx in the early 2000s, which has been adopted by USC organizations and in programming.

As discussions surrounding terminology continue to grow, so does the continuous transformation of these terms. It was in these social circles that Miguel Moran, the Latinx Student Assembly director of external affairs, was recently introduced to the term “Latine” — what Moran called the non-anglicized version of “Latinx.”

Latine evolved out of criticism of Latinx for its difficulty in pronunciation, according to a thesis by Kate Slemp of Western University. The “e” has appeared as a way to bypass gendered language and mimics Spanish’s already existing gender-neutral words such as estudiante and pariente.

Although the term “Latine” is gaining traction among the USC community informally through student conversations, the LSA executive board has not discussed using the term in a more official capacity, Moran said.

As more discussions are raised about the future of these terms, Natalia Molina, a professor of American studies and ethnicity at Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences, said that none of the terms used to describe Latinx individuals are perfect and all-encompassing. Nonetheless, they were constructed throughout time to meet a certain political moment. These terms originated as a way to be reflective of racial groups and to distinguish who was or wasn’t white, and as a result, deemed a U.S. citizen, she said.

The term “Mexican” appeared on the U.S. Census for the first time during the 1930s, and after the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 led individuals from different countries in Latin America to arrive in the United States, the labels were once again expanded to acknowledge larger pan-ethnic groups. Thus, the term Latino came into existence as a way to encompass a diverse group of people, such as Mexicans, Puerto Ricans, Cubans and Central Americans.

However, the term Latino does not fully encompass the Latinx diaspora, spotlighting certain groups over others based on name recognition, Cayetano said. Cayetano applied to the LSA executive board to expand representation for Garífuna folk, and the assembly is continuing to strive toward more inclusivity, according to Moran.

“People think that [Mexican] culture is the only Latinx culture here that exists, but not really. It’s not,” said Moran, a junior majoring in urban planning. “That’s the first step I would say that [LSA] takes in recognizing that Mexican hegemony, and not ignoring it or going against it, but kind of fighting it, fighting that stigma.”

In the past, the assembly has made active strides to redefine itself to be inclusive of all people. It changed its name to Latinx Student Assembly from Latino/a Student Assembly in Fall 2017. The change was passed by a unanimous vote in the Undergraduate Student Government Senate and marked LSA’s commitment to becoming more progressive, then-LSA co-Assistant Director Courtney Cox told the Daily Trojan in 2017.

“I think in the previous years, LSA has been very passive about a lot of issues that affect our community,” Cox said in 2017. “I think we have really tried to step forward and advocate more for our community, whether it takes place in a protest or something else.”

Student organizations on campus such as the Central American Network have also pushed for more inclusive terms at USC. That’s how El Centro Chicano became the Latinx Chicanx for Advocacy and Student Affairs in Spring 2019. The name change was controversial, however, because of its ties to activism and empowerment that many did not want erased.

Cayetano, then a member of CAN, remembers the pushback members experienced when advocating for the name change. She received texts from people questioning her advocacy on the change, claiming that she was trying to erase them from the center. Cayetano, nevertheless, remained determined.

“Why do y’all get to have your name on a plaque, but we literally don’t? And this is supposed to be a space for everyone,” Cayetano said.

A majority of these discussions surrounding the name change occurred in town halls, where some Latinx students felt it was important to keep Chicano in the name to acknowledge the historical roots of the term, which rose to prominence during the Chicano movement of the 1960s. For Consuelo Sigüenza-Ortiz, a Dornsife associate professor of Spanish, the inclusion of the term “Chicano” meant recognizing the historical impact and the continued struggles of the Latinx community.

As someone who grew up in that era, Sigüenza-Ortiz credited the Chicano movement as an opportunity for her to understand and connect with her bicultural identity. Sigüenza-Ortiz was raised in a Mexican household in Los Angeles where she struggled to navigate both Mexican and American cultures.

“I felt kind of [like] an outsider because I wasn’t fully accepted for who I was, which was a daughter of immigrant parents from Mexico,” she said. “I had to forge the identity that I wanted to identify with, not that people try to impose on me.”

Sigüenza-Ortiz, whose sister was involved in the Chicano movement, embraced her newfound Chicana identity, turning it into a learning experience and a moment for self-empowerment that helped her navigate the anti-Chicanx sentiment of the 1960s. Though the term refers directly to Mexican Americans, Sigüenza-Ortiz said she believed its impact and importance should not be erased.

“We were kind of second-class citizens and not encouraged to speak Spanish,” Sigüenza-Ortiz said. “But then the Chicano movement happened, and suddenly, there was a pride, and the arts flourished. And so it was a great time to grow up in terms of social consciousness and establishing an identity.”

According to Molina, the politicization of identity labels, much like Chicano, has risen out of a need for large groups of people to have their dignity as human beings recognized. When it came to disparities in access to resources, such as education, political representation, unions and health care, identity labels allowed for people to come together and form social movements to advocate for their civil rights.

“The idea of people being discriminated against or that they were shut out of certain resources because of their racial identity is something that people can relate to,” Molina said. “And that’s the reason that people can still come together under a broad term like Latino and say that wasn’t exactly my experience, but I see overlaps with my experience.”