The Counseling Center’s mission for more resources

On a campus where students are increasingly utilizing mental health resources, USC students are calling for additional support. In 2014, 24 Engemann Student Health Center clinicians saw 4,200 students at the counseling center. For a student body of USC’s size, this creates a counselor-to-student ratio of about 1 to 1,700. Comparatively, Ivy League schools have an average ratio of 1 to 900.

“I know from my experience and those I talk to on campus there’s been frustration with allocation of resources for mental health,” said Hannah Nguyen, director of the Academic Culture Assembly.

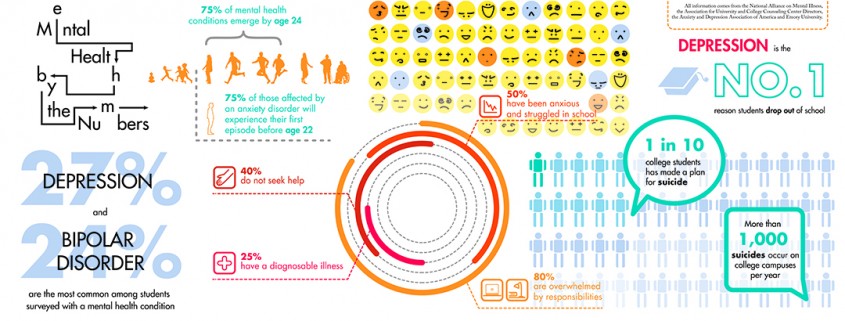

The call for mental health resources rings loud and clear at USC and across the nation due to the sheer number of students affected by mental illness. Since last year, the Engemann counseling center has seen a 25 percent increase in initial assessments and a 20 percent increase in crisis appointments. The National College Health Assessment, which surveys more than 100,000 college students, reported that 25 percent are diagnosed with a mental illness.

“I think it’s taking fire here because people are being able to talk about [mental health] more, and there’s opportunities for people to say, ‘This really does matter, this does affect my day to day,’” said Dr. Ilene Rosenstein, director of the counseling center at the Engemann Center.

Staffing and Space

A primary concern among students is the wait time necessary to schedule an appointment at the counseling center. Lianne Moreno, a junior majoring in mathematics and economics, waited a month to see a therapist during the Fall 2014 semester when she was experiencing symptoms of depression.

“It obviously didn’t make it any better,” she said.

The University’s most recent plan to hire six new counselors, announced this semester, aims to alleviate wait times. Four of the positions have already been filled, and Rosenstein hopes the remaining two counselors will be hired by Jan. 1. Already, the increase in counselors has allowed the center to reduce wait times for initial assessments from seven business days to 72 hours.

The University also plans to evaluate the appropriate number of counselors annually, said Vice President for Student Affairs Ainsley Carry. The ideal number of counselors, however, is something that is difficult to determine.

“That is one of our biggest conversations right now — what is the scope of practice and what is the ideal number of counselors to service our community?” Carry said. “We’re constantly balancing people and resources and space to meet the needs of the community as the number of people in that community continues to expand.”

One way Rosenstein hopes to decrease wait time is to continue Engemann’s preventative strategies, including stress-relief clinics, bystander workshops and group therapy. These programs aim to help students before they need individual therapy.

Additionally, students can take preventative measures to protect their mental health outside the counseling center. Mindful USC, which launched last fall, provides programming to promote stress reduction and workplace happiness. Additionally, the Office of Wellness and Health Promotion offers peer-to-peer counseling.

Additionally, students can take preventative measures to protect their mental health outside the counseling center. Mindful USC, which launched last fall, provides programming to promote stress reduction and workplace happiness. Additionally, the Office of Wellness and Health Promotion offers peer-to-peer counseling.

“We encourage students to really do their research and see what USC has to offer because a lot of resources are underutilized,” said Christine Hasrouni, director of Wellness Affairs for Undergraduate Student Government. “Whenever someone thinks mental health they think of the counseling center, but there are other things available.”

Space available for mental health resources, however, is becoming a concern. The new Engemann Center, which opened in January 2013, devotes an entire floor to counseling services, but the addition of new counselors begs the question of where they will work. Counselors who currently staff the center fill the available space, Carry said.

“Counseling is a very private and confidential relationship so we can’t just pop them anywhere. We can’t just say, ‘let’s build counseling rooms in the Student Union or in the residence halls or classrooms,’” Carry said. “Our hope is to fit them in Engemann Student Health so they’re in the same place where all our counseling services are available.”

Outsourcing: Seeking best care

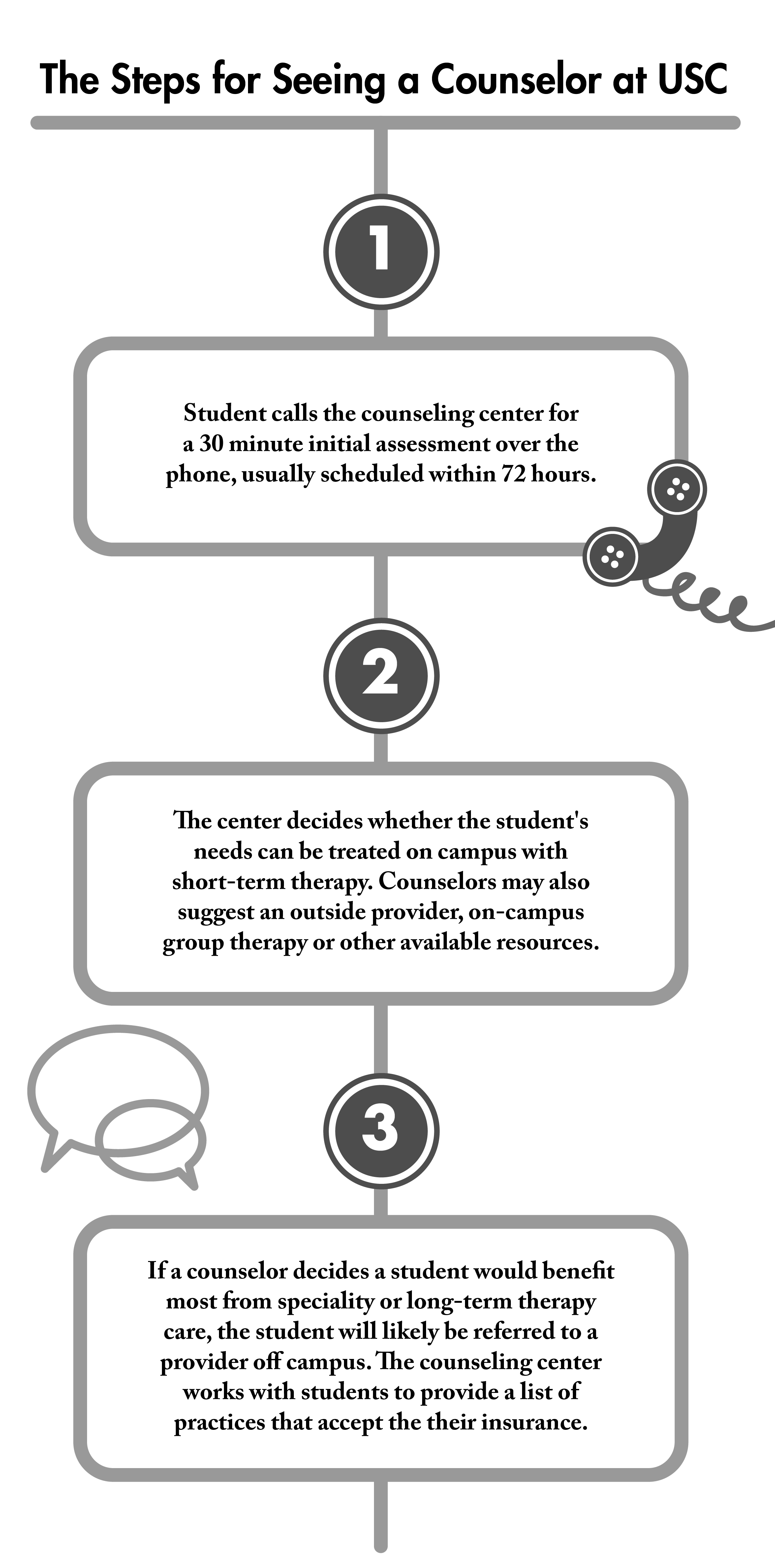

To accommodate the number of students in need of counseling services, the Engemann Center, as well other collegiate counseling centers, including the University of California system and New York University, focus on preventive and short-term care.

Following an initial assessment, if it is identified that the student needs more than short-term therapy (typically 8-12 sessions), the student is often referred to an off-campus clinician. This approach is about finding the best care, including speciality care, Rosenstein said.

“It’s not like you got rejected from counseling service — it’s because this is really good care,” she said. “We’re hoping that students and families will understand that.”

Though outsourcing can be the most efficient way for to students to receive the care they need, for some, being referred off campus can be overwhelming.

Emma Hall, a freshman majoring in biological sciences, had been seeing a psychiatrist for depression and anxiety at home when she visited the counseling center to find an available therapist. After explaining her diagnosis, Hall was referred to a clinician off campus.

Hall said her counselor was helpful in finding a provider who accepted her insurance, but taking public transportation or Uber within the first month of freshman year felt too time consuming and overwhelming, so she stopped seeking treatment. For Hall, who had always dreamed of attending USC, learning that the school could not meet her needs was jarring.

“It was my first realization that this school isn’t perfect,” she said. “Obviously this school can’t be perfect, but I was brand new and this school was my dream, so I was pretty upset.”

While referral locations vary depending on student insurance plans, two practices that the Engemann Center refers students to are within walking distance of campus, and five are Downtown. Yet 13 percent of students referred off campus for counseling stop pursuing services, according to an Engemann Center survey.

“We’re trying to figure out for those who don’t go [and] who stop, what is that about?” Rosenstein said.

The Engemann Center’s student surveys show that the top cause for outsourced students to stop seeking treatment is because they report they are feeling better or are not at a place where they needed services.

Ultimately, students are responsible for their own care, Rosenstein said, and she urges students to follow up with the counseling center if they feel their treatment plan is not working

Going Forward

The sentiments of Hall and others confused about why they cannot be seen on campus, reveal a disconnect between the counseling center and students. Hasrouni called for increased communication between the groups.

“I think one thing they can improve on is making sure that when a student is outsourced, that they are clearly communicating why the student is being outsourced,” Hasrouni said. “I think there should be more hand-holding, so if they’re not seen at the counseling center, at least they know that person is getting in with another clinic.”

To facilitate this process, the counseling center and its student advocacy team will post YouTube videos to their website that explain the process of being referred to an outside clinician. Engemann hopes to launch the updated website in the spring. The site will also feature tools to help students determine whether to seek treatment.

Hasrouni hopes that these services will be clearly outlined in new orientation programming that USG will implement next year. Additionally, Rosenstein said she plans to encourage increased communication with the student body by starting a monthly newsletter to highlight programming, continuing to meet biweekly with the student mental health advocacy group and find new ways to advertise Engemann’s events and resources.

“One of the things that was striking to us is there are all these things that so few students know we’re doing,” Rosenstein said.

As the University strives to promote its available resources, Carry is looking toward the USC Village as an opportunity to further expand mental health resources. When the Village is completed in 2017, the University will add six new residential colleges to its existing seven. This gives Student Affairs the space to explore the possibility of counselor-in-residence programs, which would aim to ease the transition of making an appointment at the counseling center by familiarizing students with counselors in the residence hall.

The University does not have a comprehensive counselor-in-residence plan just yet, Carry said, but administration is working to define what the program would look like, whether it is a counselor who holds office hours, appointments or group therapy sessions in residence halls.

Though the task of satisfying the mental health needs of thousands of students may sound daunting, Rosenstein said she believes a solution is possible once the correct number of counselors and resources is attained.

“We want our students to live up to their potential, and absolutely thrive — not just get by, but thrive,” she said.