Power and Privilege

Bridging the first-generation gap

USC welcomed over 3,000 first-generation students this year. Through both University- and student-run services, these students have redefined what it means to be a Trojan.

by tomás mier

It took her three tries to get admitted to USC.

She applied after high school. And again, as a sophomore in community college. Both times — rejected.

Every “no” pushed Roxanna Barboza closer to living her life in Lost Hills, a rural town in California, where she said the majority of people her age either work in the fields or in the oil industry. Her parents were not able to attend college. She had nothing to rely on but her education.

For children in her rural community, college did not seem like much of an option — so she created the “Colleges Out There” program for students like her to reach a college education.

Now, Barboza is studying to receive her master’s degree in public policy at USC, a school she only thought was possible to reach in her dreams.

“Having three younger siblings looking up to me, I realized that the best goal at that moment was for me to strive to go to university,” Barboza said.

Robert Feffer | DAILY TROJAN

Barboza is one of the nearly 3,000 first-generation students at USC. While many of these students share similar struggles — namely, being the first in their family to go to college — their needs differ as their identities intersect, according to Mary Ho, the assistant dean of diversity and strategic initiatives at the Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences.

“It can be overwhelming to try to navigate the university system for first-gen [students] because this is very new to them,” Ho said. “They don’t have the foundational knowledge to know what it means to be a student at a university.”

Roughly 17 percent of this year’s incoming freshmen were the first in their families to attend college, a 5 percent increase from 2010, according to USC statistics.

While the number of of admitted students from this population has grown, first-generation students like Tiaira Muhammad, a senior majoring in journalism, think that not enough is being done to address the issues of these students.

“I knew coming into USC that it was definitely going to be a culture shock,” said Muhammad, undergraduate student leader of the First Generation Student Union. “I’m from Inglewood, which is a predominantly black community. I realized my high school experience definitely didn’t prepare me enough like other students.”

She said her experience resonates with many of the other students who come from low-income backgrounds like her own. That’s why she and several other students started FGSU last year.

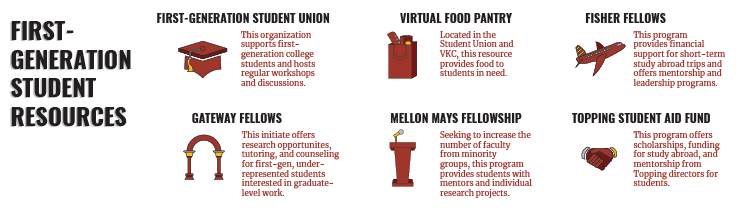

Dozens of students attend club meetings where Muhammad helps lead workshops, socials and community-related events. The FGSU is student-led and was “founded in the hopes that first-gen students would be able to find each other and raise the visibility of that population,” said Trista Beard, the group’s adviser.

“FGSU is a way to make a sort of unofficial first-gen student services,” Beard said. “But it’s students helping students and providing workshops and spaces to network. It’s not an official University entity.”

Both Muhammad and Beard wish the University would create a resource center, similar to the cultural centers already offered at USC, where first-generation students can directly receive the resources they need to succeed.

Currently, low-income and first-generation students have access to resources like the Virtual Food Pantry, where students with unstable economic situations can receive help to pay for basic expenses, Ho said.

Students are allowed to receive up to four $25 gift cards to Trader Joe’s per semester to help cover food expenses, Ho said. In addition, pantries with snacks and food are available at the Norman Topping Student Aid Fund office in the Student Union building and at the Office for Diversity and Strategic Initiatives in the Von KleinSmid Center.

There, food insecure students can grab snacks and non-perishable items.

Along with the food pantry, which may help with the day-to-day college survival, first-generation students can also apply to fellowship programs like the Fisher, Mellon Mays and Research Gateway Fellowships, which push their college careers past the undergraduate level.

Fisher Fellows receive financial support to attend Maymester and Problems Without Passports programs along with a retreat at Catalina Island. They also take part in mentorship and leadership seminars hosted by faculty and alumni.

Gateway Fellows are offered research opportunities that “aim to diversify the student bodies at the graduate-level and the professoriate ranks,” according to the program’s website. The program offers academic tutoring and counseling, as well as seminars to help scholars take part in graduate-level work.

Similarly, the Mellon Mays program is made for the advancement of minority students in higher education and is specific to students who want to become professors and pursue doctoral education, according to the program’s website. Students receive stipends each semester and are given the opportunity to do research while at USC.

Natalie Solis, a senior majoring in religious studies, is both a Gateway Fellow and a Mellon Mays Fellow. She transferred from Barnard College in New York City to take advantage of these opportunities, which enabled her to work on three independent research projects.

Her most recent research project delved into how murals of the Virgin of Guadalupe help create sacred spaces for the Latinx community in Boyle Heights.

“I wouldn’t be applying for graduate school if it weren’t for those programs,” Solis said. “Increasing diversity within higher education is done by supporting students of color while they’re undergraduates.”

While these resources are available, accessing and finding them can be tough for students new to USC, Ho said.

“[First-generation students] don’t know what they don’t know, but if we’re able to centralize information and resources, and also educate our faculty and staff about what’s available, then they can share that with a student they’re meeting with [and help guide them through that process],” Ho said.

Muhammad said she wants FGSU to emulate what is currently done with the Norman Topping Student Aid Fund, a scholarship and retention program that helps nearly 200 low-income, first-generation students.

With NTSAF, not only do students receive economic help with their yearly and study abroad expenses, but they also have access to an office where students can come in and take advantage of the open-door policy offered by program directors Beard and Christina Yokoyama.

“If we could be bridges to campus resources, scholarship offices, financial aid, multicultural resources, that’s the best work we can do,” Beard said. “It’s to open the door comfortably and get the student the ‘warm hand-off.’”

Topping Scholars, as recipients of the NTSAF are called, are invited to a retreat prior to the school year where they can meet each other and learn about the resources available to them.

Throughout the year, Topping Scholars are invited to mentorship programs and events to aid them throughout the college process.

That’s where, for Muhammad, the Topping Scholars become a family.

“These are people that are genuine family to me,” Muhammad said. “And that’s what First Generation Student Union is trying to create as well.”