Civil rights advocate to serve on ethics commission

Ralph Fertig, a clinical professor of social work, has a history of working for civil rights. As a new member of the City of Los Angeles’ Ethics Commission, he will now use his moral compass to guide elections.

“This very much integrates with what I’m teaching and studying, which is public policy,” Fertig said. “It’s very fundamental that both local and national concerns are only addressed in adherence to a code of ethics.”

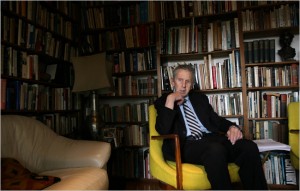

Equality · Ralph Fertig, a professor of social work, was unanimously confirmed to the City of Los Angeles’ Ethics Commission last week. - Photo Courtesy of Ralph Fertig

He was unanimously confirmed last week to the commission, which oversees campaign finance and lobbying laws for city officials. He said his belief in transparency and equality in democratic elections will guide his decisions.

“The funding of campaigns and the relationship between vested interests and the record of [a] candidate or incumbent need to be in the light of day,” Fertig said.

Fertig was instilled with a sense of ethics from a young age. After his parents fled European fascism, refugees from World War II would stay in his family’s apartment in Chicago.

“I grew up with stories of atrocities from people who had experienced them and I dedicated my life to guaranteeing democratic and ethical principals,” Fertig said. “They assured me of the rights to the people. I was raised on the concept of unalienable rights.”

Fertig has dedicated his life to extending rights to oppressed peoples through nonviolence.

“Along the way we’ve had massive resistance of that extension, calling on people to accept the notion that equality means giving up the monopoly on power. There’s naturally resistance and fear and resentment,” Fertig said. “It’s not a steady outpouring of what’s right, but a battle to get people to give up monopolies on power so it can be shared with the full community.”

While working for Chicago Freedom Action, a civil rights group that worked to overcome racism and discrimination for African Americans, Fertig participated in the Freedom Rides, which tested a Supreme Court decision that made it illegal for cities to enforce local Jim Crow laws for bus riders. This ride was initially set to be called off because of violence from white supremacists who attacked people riding the buses.

“We went to Jackson, Miss. … After many efforts … we found a bus driver to take us,” Fertig said.

[Correction: A previous version of this story said that the bus driver abandoned the bus riders in Selma, Ala. When the bus arrived in Selma, a sheriff arrested Fertig, but the other freedom riders proceeded to Jackson.]

Four years later, a series of marches shifted public opinion toward the civil rights movement but, in 1961, Fertig was arrested [in Selma].”

“The Klu Klux Klan was along the outside and egged on white prisoners to beat me so their white supremacy was espoused,” Fertig said. “They broke every rib in my body and I was rescued from the courthouse by [three] very brave black lawyers.”

[Correction: A previous version of this story stated that two lawyers aided Ralph Fertig. It was three lawyers: Fred Grey, Solomon Seay Jr., and Charles Conelley.]

Now, Fertig is one of four members on an executive committee that supports efforts to investigate murders of civil rights activists in Mississippi.

Fertig said the group continues to meet every Wednesday.

Fertig’s firm commitment to civil rights landed him in front of the Supreme Court two years ago when he challenged the 1996 Patriot Act, which makes it a crime to provide “material support” to a terrorist organization.

[Correction: A previous version of this article stated that Fertig advised the Kurdistan Workers Party. He has advised Kurdish groups and people, but not the Kurdistan Workers Party, which is considered a terrorist organization by the United States.]

“I am seeking a peaceful alternative to the violence that is being dealt upon the Kurds by the Turkish government,” Fertig said. “The Supreme Court said I was doing the exact opposite.”

In a 6-3 decision, the court ruled that Fertig could not advise the Kurdistan Workers Party because national security was threatened.

He said this doesn’t discourage him, but encourages him to find other ways to help the Kurds.

“That’s all the more reason to become engaged in political alternatives,” Fertig said.

In addition to his teaching and activism, Fertig wrote a Los Angeles Times bestseller in 2001 about Jewish liberation from ghettos during Napoleonic era.

“My novel incorporates the details of racism and confinement, seen through the eyes of people,” Fertig said. “It is largely fictionalized — the historical details are accurate and the historical figures are accurate and saying things they said — but the point is that you can never be liberated without love and you cannot love without liberation.”

He said that the civil rights of nonviolence and love are the keystones to all of his work.

“I don’t think that one can be a professor of social work without being an humanitarian. Social work is the humanitarian profession,” Fertig said. “It is the one profession that exists for the purpose of securing rights and respect and equal opportunities for all peoples.”

He is a national treasure.