Living the Dream: How Sam Darnold went from USC fan to Trojan hero

The home where USC quarterback Sam Darnold grew up is quiet and peaceful on a Monday night.

Signs of his success fill every corner of the room — the unwashed Rose Bowl jersey hung on the wall, the team MVP trophy on the coffee table, the Army Bowl helmet on the counter in the kitchen.

“Coach [Clay] Helton sat on that couch and we talked about winning a national championship,” Chris Darnold says, patting the cushion next to her.

She laughs, shaking her head. In two years, a dream that once seemed far off is becoming an expectation.

Chris and her husband, Mike, know that their son is special. In the last year, he’s become the starting quarterback for one of the best college football teams in the country, a Rose Bowl champion, the top contender for the Heisman Trophy and a potential No. 1 NFL Draft pick.

Yet in many ways, he’s still the same kid who first picked up a ball in San Clemente. And in his slingshotting arc to fame, Darnold has become an enigma to anyone outside of his select group of family and friends.

He’s a competitor who doesn’t raise his voice outside the huddle. In a world of NFL and college celebrities who pick fights on Twitter, Darnold is a star who hardly messes with his phone. He describes himself as reserved, soft-spoken, hard to read on and off the field.

“I think I’ve always been a shy guy,” Darnold said. “I’m not someone to go out of my way to meet somebody or make a fool out of myself, and I don’t think I have to change. I think I can definitely just remain myself.”

He’s not one to boast or to talk trash. But for anyone wondering, Darnold’s next plans involve two simple steps.

Step one: Win.

Step two: Don’t stop.

How did he do that?

As a kid, Darnold was easy to please. If his parents wanted to take him somewhere, they only needed one thing — a ball. It didn’t matter if it was just a half-hour drive to his grandparents’ house. Darnold was happiest with a ball in his hands, shooting hoops or playing catch.

His family jokes that they could never convince him to watch “normal” TV shows. He’d beg to turn the channel from Spongebob to ESPN, happy to watch a tennis ball going back and forth, rather than the typical cartoons that amused 4-year-olds.

The Darnolds are, above all else, a sports family. Sam’s grandfather played basketball for the Trojans. His family held USC season tickets for his entire life. His older sister, Franki, played volleyball at Rhode Island.

For those who know Darnold, none of his current success is a surprise. It’s just the next step in the path that he’s been walking since he first tossed a ball.

At first, his parents thought it was just the overconfident support that every parent holds for their kids. But it quickly became clear that no matter what field or court Darnold was on, he was always the best. He made parents do double-takes with his casual displays of intuition and athleticism.

The first time it happened, Darnold was playing first base for his T-ball team. He snagged a pop fly, tagged the base and then threw another runner out to turn a triple play. He was five.

From the stands, his parents thought the same thing — how did he do that? It’s a question that’s followed Darnold ever since.

As Darnold grew up, his athleticism evoked that same question over and over. At times when he appeared outmatched or completely beaten, he adapted his play or strategy to find a way to win. Family, teammates and friends were consistently left shaking their heads, bemused because Darnold, somehow, had done it again.

It was simple. He just had to win.

In the eighth grade, he entered his school high jump competition. His competition stood inches taller than him and jumped with proper form. Sam didn’t know a Fosbury flop from a belly flop, but he tossed his body into the air with enough passion to earn a spot in the final.

Mike came to the event to offer his support, expecting Sam to take a participation trophy. Instead, he watched his son leap 5-feet-3-inches into the air to take home first place. He was surprised, and yet, it was typical. Sam was never one to lose.

It was a reaction that even shook Helton when he watched Darnold play as a high school senior.

It was Helton’s first time seeing Darnold in action. His high school coach, Jaime Ortiz, knew that staying calm was the key to the night — most high school players tense up when a coach or scout comes to their game, taking at least a few snaps to loosen up into their regular style of play.

Not Sam.

He threw 12-for-12, notching 180 yards and five touchdowns. After each score, he celebrated in his customary fashion — a quick jog to high five his receiver, then to the sidelines, occasionally pointing skywards as the student section roared.

At the half, the two coaches met before Ortiz headed into the locker room.

“Coach, I’ve been recruiting a long time,” Helton said. “I’ve never seen a player do that.”

As a quarterback, it’s this quality — the “it” factor, Ortiz calls it — that sets Darnold apart. Trojan fans enjoyed a boon of that, from his scrambling fumble-turned-touchdown-pass against Colorado to his half-field bullets that hit receivers right in their palms.

His “it” factor reached a peak in the Rose Bowl, when even the commentators abandoned their unbiased composure to ask, yet again, how Darnold managed each of his rocketing passes to tie the game.

“Some people are born to do things, right?” ESPN announcer Chris Fowler marveled as a touchdown pass replayed in slow motion. “Some people are put on this earth to do one thing. He is a born quarterback.”

For the love of the game

The funny thing is, Darnold didn’t want to be the football star.

His love for football was undeniable. But until his sophomore year of high school at San Clemente, Darnold saw himself as a basketball player, idolizing the likes of Duke’s J. J. Redick. He played anything from guard to forward, making his school’s varsity team as a freshman and winning League MVP as a sophomore and a senior. Even though he split his time evenly between the field and the court, basketball had always been the sport that fit him best.

It took a few things for that to change.

He’d played quarterback since the third grade and been a USC fan since long before that. Most of his idols as a little boy were football players — Trojan football players.

“Reggie Bush, Matt Leinart.” Darnold named them one by one, keeping track on his fingers. “Carson Palmer, Mike Williams. I can keep rattling them off but it would probably take me an hour.”

In the third-to-last game of his sophomore football season, Darnold was tossed into the quarterback role after the starter suffered a season-ending injury. The next week, he took the helm against Tesoro High School, the

fifth-ranked team in the county. The end of San Clemente’s season rested on trusting Darnold, a sophomore who hadn’t thrown in a game since middle school.

Darnold should’ve been nervous, made rookie mistakes. Instead, he kept his team neck-and-neck with Tesoro until the final quarter. With 15 seconds left on the clock, he launched a 45-yard pass to tie up the game. With time expired, he rolled out on a bootleg and threw a game-winning touchdown to his tight end.

From the sidelines, Ortiz knew something special had just happened: Darnold had arrived.

The next week, former Utah offensive coordinator Aaron Roderick watched Darnold in his second game as a quarterback. He offered him a scholarship on sight.

“Remember that we were first, OK?” Darnold remembers Roderick saying as they shook hands. The words held a hidden truth — Utah certainly wouldn’t be the last.

The road that followed was rocky. Darnold became a starter for both the football and the basketball teams, splitting his time between his two favorite sports.

He went 2-0 in his first season as starting quarterback, until a rough tackle left him limping. In typical Darnold style, he finished the drive and threw a touchdown pass before he walked to the sideline and dropped to the ground.

X-rays showed a foot fracture, and the rest of the season was spent gritting his teeth and riding the bench. Darnold’s football team didn’t win another game. He tried to force his way back onto the field, but his coaches, parents and doctors forced him to be patient.

Darnold waited, healed, labored through physical therapy. Then his team lost his first basketball game back on the court, and Darnold made one of the few rash decisions of his life: He slammed his fist into a locker in disgust. The split second of anger cost him a broken finger and the rest of his junior season.

At that point, Ortiz stepped in.

The kid was undeniably talented. With only four games worth of film footage, he’d earned an offer from Utah and interest from a handful of other universities. But Sam’s lost junior season left him far behind the typical recruiting curve. In a sea of talented quarterbacks who were happy to hype their success on every social media platform, Darnold needed to stand out.

“I looked up to everyone who played USC football honestly,” Darnold said. “That’s not a cliche because I’m the USC quarterback. I honestly loved USC football. I want to leave a legacy like they did. Hopefully I can be that role model for a kid out there who loves watching football.”

But Darnold, for his part, didn’t like being recruited.

He didn’t want to play on a 7-v-7 team or attend sponsored camps. That wasn’t football. Not to him. But Ortiz forced him to get on social media, to travel to Nike camps, to sell himself as a college prospect.

From there, his recruitment process was simple. Once a program saw him throw, a scholarship offer quickly followed. And like anything, the accolades came as well — Elite 11 rankings, top placements at quarterback camps and attention from across the country.

Coaches took three-hour flights to check him out. Chris spent weekend mornings making breakfast burritos for Sam’s teammates as they caught passes for hours with scouts from everywhere from Tennessee to Oregon. It seemed that at least half of the top programs in the country wanted Darnold except for the one that mattered — USC.

That offer almost came too late. Darnold was planning a trip to visit his final schools when former head coach Steve Sarkisian called. There was barely a week left before the dead period of recruitment began, and the Darnolds honestly didn’t know if there was time to fit the Trojans in.

So Sarkisian and Helton — then the offensive coordinator — adjusted their schedules, letting Darnold come up that weekend to throw. An assistant coach chased after his passes for hours as the two coaches watched. The offer came that day: If he wanted it, Darnold had a home at USC.

For Darnold, it was a dream come true.

“I looked up to everyone who played USC football honestly,” Darnold said. “That’s not a cliche because I’m the USC quarterback. I honestly loved USC football. I want to leave a legacy like they did. Hopefully I can be that role model for a kid out there who loves watching football.”

Drive it like you stole it

“I just do my thing.”

It’s the best way that Darnold can describe his mental process in the pocket.

He’s not being glib. He’s not avoiding the question. He’s certainly not playing dumb. But for Darnold, a lot of the confusion of playing quarterback — reading routes, converting botched plays, avoiding blitzes — comes naturally.

“I go back to Pop Warner games and just have fun playing the game,” Darnold said. “I think there’s something to be said for that. It’s fun for me and I think it’s fun for the crowd as well.”

The game slows down for him. He doesn’t think too hard, doesn’t overanalyze. When he plays, he stays comfortable, rolling with whatever feels right in the moment. His approach is almost casual. It’s different, unstructured, and when it works it’s a thing of beauty.

Sometimes, however, it’s a weakness. Sam coughed up four fumbles in his first six games alone, and tossed nine interceptions over the course of the season. His tendency to scramble sometimes left him vulnerable in the backfield, and hard hits often led to turnovers.

“I told Helton from the very beginning that Darnold would run through walls for him,” Chris said. “If you let him. You give him the shot and he’ll run through walls for you.”

But those mistakes didn’t keep Sam from generating over 3,300 total yards of offense in 13 games. In fact, Ortiz believes that his gutsy decision making is the key to Sam’s success.

It all plays into Helton’s mentality on running the offense — drive it like you stole it. He pushes Sam to create an up-tempo style of play that challenges defenses on all fronts, gambling at times and trusting that the reward outweighs the risk. That style of play fits Sam like a glove.

“You give him the keys to your car, he may dent it, he may scratch the paint,” Ortiz said. “But when you let him go and you let him drive that car, good things are gonna happen.”

That doesn’t mean that Darnold is satisfied, however. Far from it. He wants to scramble less, stay in the pocket to read the defense and protect the ball. He self-identifies as his own worst critic, eager to point out room for improvement in every aspect of his game.

And that’s why, for the Trojans, Darnold has become the man. He’s never satisfied, never finished, and he refuses to settle for second-best when he believes he can give his team more.

“I told Helton from the very beginning that Darnold would run through walls for him,” Chris said. “If you let him. You give him the shot and he’ll run through walls for you.”

Save me a seat

Two years ago, when Darnold was just a redshirt freshman, Ortiz shot him a text as Derrick Henry accepted the Heisman award.

“Before your career is done, you’re gonna be on that stage one day,” Ortiz wrote. “Save me a seat.”

Darnold waved it off. He wasn’t even a starter yet, and besides, that wasn’t why he was playing. Even now, as expectations for his success grow, he refuses to pay attention to the hype.

Fame hasn’t changed Darnold, and that’s mainly because fame is the last thing he cares about.

Darnold wants to win. He needs to win. He is persistent, ambitious, tenacious. But none of that competitive fire is focused on trophies or awards or even draft picks. Darnold wants to win in the same basic, natural way that little kids want to win backyard basketball games and impromptu foot races.

“He plays just like when he was little,” Mike Darnold said. “He plays exactly the same. He just keeps getting smarter and better. I think he likes who he is because he’s remained the same.”

It’s hard for Darnold to stay incognito on campus anymore. He’s grown used to it — the double takes, the questions, the requests for selfies. Even high school friends shyly ask for autographs when he comes home to San Clemente over breaks. And that will only grow next season, when the student store will sell his jersey number and his picture will headline every game program and poster.

Yet despite his rising status as a star, Darnold remains the same. Levelheaded yet competitive. Calm yet relentless. Ortiz calls him a poker player, even keel, soft spoken. His parents described him in one word — flatline.

“Unless he’s hungry,” Chris jokes. But besides that, her son still seems the same, flashing that same little grin from behind his helmet after tossing a touchdown as he did when he played Pop Warner.

He doesn’t dance midfield during timeouts or celebrate in the end zone. In post-game interviews, he’s

stone- faced, calmly diverting attention from himself by praising his teammates and coaches. Even in the Rose Bowl, in the game of his life, Darnold only showed emotion once, holding his helmet aloft and shouting as the winning kick sailed through the uprights.

“If I get whatever records, you know that doesn’t mean much to me,” Darnold said. “I just want to win games. I want to win a national championship before I leave here, but I don’t look too far forward. I focus on today. Every single day I just try my best in every single thing I do.”

That’s just Sam. He’s the star who still comes home on weekends and breaks, hanging out on the couch in Ortiz’s office at the high school, lifting weights at the middle school where Chris works. He’s close to his family, the type who buys personalized necklaces for his mom and sister for Christmas, who still makes it to cousins’ volleyball games and catches basketball games with his dad.

Yes, he might win the Heisman, and he might go No. 1 overall. But for Darnold, all that will actually make a difference is making sure that his team wins every game. The legacy he wants to leave is simple — a legacy of winning games and championships, of returning USC to its former glory.

“If I get whatever records, you know that doesn’t mean much to me,” Darnold said. “I just want to win games. I want to win a national championship before I leave here, but I don’t look too far forward. I focus on today. Every single day I just try my best in every single thing I do.”

Darnold’s life has been cemented by football, by stories of a little redheaded boy in Matt Leinart’s No. 11 and Bush’s No. 5. For him, it wasn’t just playing dress-up or make believe. When he wore those jerseys, he saw himself as one of those players — Leinart lining up his offense, Bush diving into the end zone.

Even now, as he trains to take his team to a national championship, Darnold remains the same little boy who dreamed of throwing passes in the NFL. He’s a little bit taller, a little bit better, but he’s still a kid living his dream.

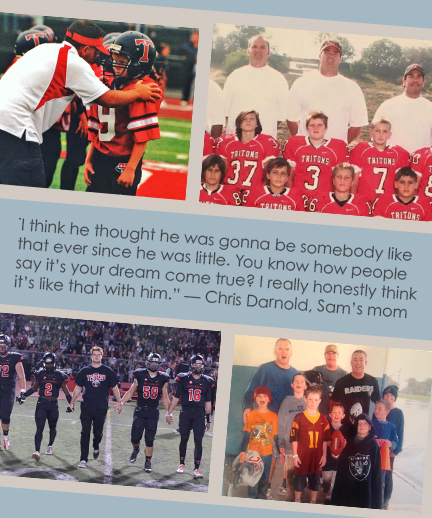

“I think he thought he was gonna be somebody ever since he was little,” Chris said. “You know how people say it’s your dream come true? I really honestly think it’s like that with him.”

And for Darnold, that dream is only getting started.