Obama’s contribution to youth vote exaggerated

Conjuring up in the collective mind of America’s citizenry nasty images of fist-slamming old men frothing at the mouth over matters of precious little consequence, politics is so unsexy it’s criminal. It’s a crying shame, really, that this is so, because it means that politics fares most badly among the looks-obsessed — which is to say, among the young.

Until now, right? Obama is largely credited with giving politics its sexy back; young people rallied behind him in record numbers, elected him president and won back their political voice. Right?

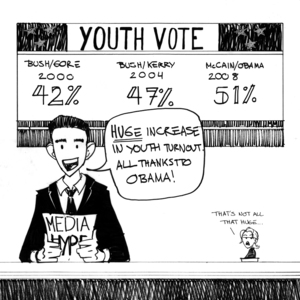

Well, not exactly. Obama merely added a few drops of fuel to the fire, happily taking the credit given him by his loyal band of media followers for single-handedly igniting youth involvement in politics. Actually, that fire started in 2004, with sparks beginning to fly in 2000 — nearly a decade before the age of Obama.

Young people — by polling standards, 18- to 29-year-olds — have always had a curiously on-again, off-again relationship with politics, and are notoriously fickle in their voting trends: up in arms one minute, down for the count the next. In 1972, when the voting age was lowered to 18, they made a particularly grand showing at the ballot box: 55 percent of 18- to 29-year-olds voted in that year’s presidential election, according to the Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement.

There hasn’t been that high a turnout since.

After a particularly dismal showing among young voters at the 1996 presidential election — some 39.6 percent — something changed in 2000, a small uptick. Then in 2004, the fire came (back) to life: Nearly 50 percent of 18- to 29-year-olds voted in that year’s presidential election, which CIRCLE estimates was an 11-point increase from 2000. The controversial Bush-Kerry race — hilariously lampooned by a brilliant JibJab video, which quickly went viral and got kids everywhere talking politics — coupled with inventive new outreach programs and shifts in attitudes essentially re-enfranchised a new generation of young people.

That was 2004.

We have since forgotten this original surge and focused solely on the one which came next, in 2008, which was actually considerably smaller — a fact largely ignored by the media.

Time Magazine called 2008 the “year of the youth vote,” saying of Obama, “His campaign has become the first in decades — maybe in history — to be carried so far on the backs of the young.” The media lavished on the praise, raising its collective hands in exultation and praising Obama for doing the seemingly impossible: getting us to care.

Undoubtedly, Barack Obama’s early victories in the Democratic state primaries last year, especially in Iowa, were due in large part to the youth vote, and no one can say otherwise. But given the exorbitant fuss made over the so-called “youthquake” his campaign supposedly engendered — a breezy term the media couldn’t get enough of — one might have expected a record turnout during the actual election among young voters. Alas, no: Gallup polling found “little evidence of a surge in young voter turnout beyond what it was in 2004.”

Why, then, does Obama get all the credit for galvanizing the youth of America? Part of it is that the surge in 2004 was underreported while the “surge” in 2008 — which in reality was but a couple more percentage points, if that — was vastly overreported. The media wasn’t exactly enraptured by Bush or Kerry, but Obama was another story, a new breed of politician, so fresh (and fresh-faced) with his message of change and audacity of hope that if anything good happened in American politics, there was really only one man to whom credit was indubitably due.

There were other reasons for Obama’s (perhaps undue) lionization among the young, chief being that he was running as a Democrat, and — for better or worse — most newly politicized young people are also often Democrats. Democrats have an easier time gaining young converts. It’s no secret that the young tend to be more idealistic; not surprisingly, the increase in the youth vote from 2004 to 2008 mostly favored the Democrats — though John McCain’s stodginess might be partly to blame for that.

And so it goes: Obama wins.

But really, should we care who gets the credit? Honestly, probably not, and Obama would be the first to say that it matters less what caused the surge in youth voting than the surge in youth voting itself. Time will tell if this trend continues. Hopefully it will. In the meantime, we can rejoice in our newfound civic-mindedness (or more than half of us can), thank a decade of politicians who decided we mattered and hope the flame continues to burn a while longer.

Politics might just be sexy yet.

Jason Kehe is a sophomore majoring in print journalism.