Franco’s performance gives film a powerful edge

Dear James Franco,

Look at how far you’ve come. First it was that stint on Judd Apatow’s short-lived Freaks and Geeks. Then you surprised us with some commendable method acting in James Dean. And you did some decent work in your role as Harry Osborn in the Spider-Man trilogy — well, maybe not the third movie.

But with all that success, we thought you might have lost your way: Tristan and Isolde, James? Annapolis? Perhaps James Dean was a bit of a flash in the pan, some said. We can’t lie; sometimes it seemed that you had grown content walking the path of the pretty-boy lead man. No one would have blamed you.

It was with a slight surprise that we noticed you in Judd Apatow’s film Pineapple Express. You, as a happy-go-lucky weed dealer, prone to bumbling moments and silliness involving innovations in joint technology? It was new. And we liked it.

Milk was another surprise. We didn’t necessarily pin you as being perfect for the role of politician Harvey Milk’s gay lover, but it happened. And you pulled it off.

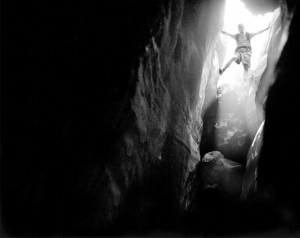

But nothing could have prepared us for your role as Aron Ralston in Danny Boyle’s new film 127 Hours. Ralston’s true-life story of being trapped in the Utah desert — arm pinned by a boulder — needed a powerhouse performance to work on screen.

As the only major character in the film, whoever played Ralston needed a fearless performance to captivate audiences for the entire ride. We needed to love the character. And you, James, you stepped up to the plate and delivered the performance of a lifetime.

Congrats.

Let’s face it. This movie could have fallen flat on its face. Being a true story, everyone already knew the ending: Ralston went hiking, fell into a crevice and got his arm pinned forcing him to take drastic action. 127 Hours really wasn’t going to be about what happened; it was going to be about Ralston’s experience.

This is where you stepped in. From the minute you arrived on screen, it just felt right. Ralston’s life-on-the-edge, no-strings-attached attitude was perfectly played, all bright eyes and smiles.

But you also communicated Ralston’s desperation, his anxiety and his wild-eyed paranoia. You somehow effortlessly managed to pair your own agony with chuckle-inducing, cornball laughs. And that bloodied, spittle-laced finale was the stuff of legend. We all knew what was coming, but the triumph still lifted our hearts into the stratosphere.

And how was working with director Danny Boyle? Not to take anything away from you, but Boyle’s filmmaking was simply astonishing, which in turn let your performance shine as bright as it could. Not just any director can be so courageous with his stylistic decisions, after all. The editing, effects and cinematography could have teetered over into the abyss of the pretentious. But it didn’t.

Instead, Boyle’s directing expertly framed Ralston’s subjective affair, pulling depths of emotion and history seemingly out of nowhere. The little details — an imaginary laugh track as Ralston pretends to be on a talk show, or the intricate, seamless cross-cutting of past and present — made it possible for us to sympathize with Ralston’s perspective.

And so when his mind stumbles into the schizophrenic, we are right there, gasping, cringing and laughing with you on screen. The suspense could have been suffocating but instead was managed by slivers of comedy. And piece by piece, Boyle reveals your character to us, simultaneously mirroring Ralston’s own self-discovery.

So many directors these days can’t seem to understand that style and form alone is meaningless. We are thankful that Boyle displayed that he is not one of these clueless filmmakers, poring over jump cuts and filters without finding a purpose for such effort. It felt good watching a movie that worked on both levels: as a piece of entertainment and as a piece of critical art. It’s not something that should be taken for granted.

Consider, for instance, all those clever metaphors. The Nalgene bottle sitting in the sink, overflowing with water. That eternally present camcorder, a self-reflexive nod to the art of filmmaking. The montages of crowds in motion that bookended the film. The crow that regularly flew over Ralston’s head.

Did Boyle ever mention all these little clues to you, James? Don’t worry, you don’t have to tell us what they mean. It’s not a bad thing for the audience to have to think once in a while.

By the time the credits rolled, it felt like this movie came together exactly how it was supposed to. It’s a rare thing when real-life stories can be told so honestly without overreaching their realistic boundaries, as some Hollywood films do.

We have you, Boyle, and all parties involved to thank for bringing Ralston’s astounding story to the big screen.

But best of all, 127 Hours wasn’t just about Ralston. It taught us a little about our own intricate moments of brilliance, along with our failures as human beings. Selfishness alongside determination alongside stubbornness alongside revelation.

It probably wasn’t an easy film to make, and it certainly wasn’t an effortless film to watch. At the end of the day, however, you were the key to the execution of it all. And you made it happen, James. Thanks.

Sincerely,

The audience