Activist doc raises questions of truth and media

“Knowledge can help to transform the world. Knowledge does not exist in a dimension of its own, but rather it can be active. It can be practical.”

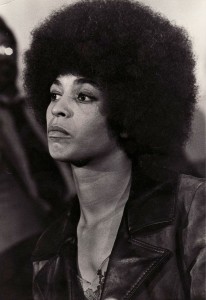

Powerful woman · Free Angela Davis and All Political Prisoners focuses on a narrow portion of Angela Davis’ life in the ’60s and ’70s as the social activist worked to navigate the post-civil rights movement landscape. – Courtesy of Angela and Fania Davis

So says Angela Davis in Shola Lynch’s new documentary, Free Angela Davis and All Political Prisoners.

Yes, that Angela Davis. Though modern audiences will remember the controversial 1970 trial in which Davis was accused and then subsequently acquitted of murder and conspiracy against the government, the real story, one told from Davis’ own perspective, hasn’t reached the mainstream — until now.

Lynch’s film follows Davis’ triumphant story as she describes her days teaching philosophy at UCLA, dealing with the hostile anti-activist atmosphere of the late 1960s and early 1970s and, ultimately, facing imprisonment after she appeared on the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted Fugitives list. Produced by the likes of Jada Pinkett Smith and Shawn “Jay-Z” Carter, the documentary has caught the attention of notable stars of the industry, making a name for itself as perhaps one of the most honest depictions of a time period tainted by biased media coverage.

“Her story is so much more extensive in this particular documentary than in other pieces that I’ve seen about her,” Pinkett Smith said in an interview with the Daily Trojan. “That was one of the reasons why I decided to support this particular documentary.”

Free Angela Davis and All Political Prisoners focuses on a narrow portion of Davis’ life, namely her time with the black-communist Che Lumumba Club and her struggles to clear her name in the Marin County courthouse case. When a 17-year-old Jonathan Jackson used a gun registered in Davis’ name in a failed courtroom kidnapping attempt, Davis was quickly accused of conspiracy and shuttled into a life of outrunning the FBI and prove her innocence.

“Because that particular aspect [of Davis’ story] was so complicated and so layered, [Lynch] wanted to leave a lot of room to tell that story,” Pinkett Smith said. “If she had added her childhood and even all the things that happened after that particular trial, we probably would’ve had a 10-hour documentary.”

But even with this focus, the film makes it perfectly clear that the FBI wasn’t the sole source of Davis’ troubles. Lynch thrusts viewers into the unsettled landscape after the civil rights movement, a landscape that contributed to an extremely troubled America where social activism was often met with deadly consequences.

“It was as if we were living in a state of war, in a state of seize,” Davis says in the film. “For us, during that period, the revolution was right around the corner, and we had to do everything we could to usher it in.”

Lynch includes a series of figures from Davis’ life to round out her fresh depiction of the political icon. Davis’ friends Bettina Aptheker, Margaret Burnham and her sister Fania Davis Jordan all discuss their international campaign to free Davis from prison and advocate for political freedom. Davis herself talks at length about her thirst for change, her disapproval of the Black Panther Party’s male-supremacist ideologies and her unwavering sentiment that silence and freedom don’t go hand in hand.

Using a remarkable series of historic photographs, video footage and media coverage, Free Angela Davis and All Political Prisoners quickly ushers viewers into Davis’ world. We see Davis throw up the black power fist on the morning of her trial, give charismatic speeches to her UCLA students and express her love and admiration for fellow activist George Jackson. Gone is the impersonal, stereotyped image of a dangerous Davis who advocated violence and conspiracy.

Instead, Lynch brings viewers into an intimate conversation with a woman who defied America’s notions of radicalism and showed what it meant to be revolutionary.

“[I realized] how serious they were,” said Davis, reflecting on the grim attitudes of the judge and jury of her courtroom trial. “[And it made me realize] that it wasn’t about me. It was about the construction of this imaginary enemy. And I was the embodiment of that enemy.”

Through Davis’ experiences, however, the documentary asks larger questions about the criminal justice system and the role of the media in historical events. In a particularly stunning sequence, Lynch splices together snippets of former President Ronald Reagan referring to Davis’ hiring at UCLA as “a deliberate provocation” and clips of her colleagues applauding her ability to draw 2,000 students to her first lecture. Other parts of the film involve journalistic outlets denouncing Davis as a radical communist while Davis herself calmly rallies with her intellectual followers.

“It’s very interesting to see that relationship between a subjective point of view and having an objective point of view and being able to, as a journalist, really investigate something,” Pinkett Smith said. “I think that’s why a lot of us had a misconception about Angela Davis.”

And Lynch certainly does away with our misconceptions. Through touching interviews and insightful historical footage, Free Angela Davis and All Political Prisoners invites us to question not only what we know about Davis’ history, but also the way knowledge of historical events is transmitted to a broader audience.

At the same time, however, Lynch also divulges new information that might make even the most studied experts of the Davis trial leave with answers they never knew they needed.

“[Davis looked] over to me and she said ‘I never knew how they got me,’” Pinkett Smith said as she reflected on watching a screening of the film next to Davis at the Toronto Film Festival. “She was talking about the FBI. … And in that moment, I said to myself ‘If there’s not another person that ever sees this film, it would never matter to me.’ The fact that I was able to participate and bring that story to life, that Angela Davis watched and learned something about herself. [I knew] this film is much more important than I ever thought.”

Free Angela Davis and All Political Prisoners opens today at select AMC theaters.