New exhibit combines art and science

“This remarkable phenomenon, of whatever value it may turn out in its application to the arts, will at least be accepted as a new proof of the value of the inductive methods of modern science,” William Henry Fox Talbot wrote in 1839.

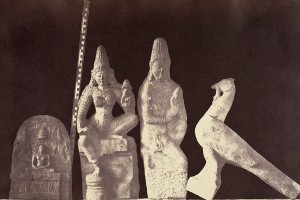

Progressive photography · Linnaeus Tripe’s 1858 photograph of “The Eliot Marbles” is a piece that relies heavily on the use of negative space. In 1857, Tripe became the official photographer to the Madras government. His trip to Madras resulted in a photo collection entitled Burma Views. – Photo courtesy of LACMA

Here, Talbot — a pioneer of photography and inventor of the calotype — speaks to the transcendent nature of the art form. Photography is very technical in nature, yet still fits perfectly well into the humanities in the art that it produces.

This interconnectedness of art and science is a leading theme in “See the Light — Photography, Perception, Cognition: The Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection,” a new exhibition at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

The exhibition pulled 220 photographs from the roughly 3,600 found in the Vernon collection, which LACMA acquired in full in 2008. The pair had collected photography since 1975.

The exhibition was broken up into four parts: descriptive naturalism (Talbot’s quote was pulled from the accompanying text here), subjective naturalism, experimental modernism and romantic modernism, with a camera obscura room toward the end and a video project from David Hockney, “Seven Yorkshire Landscape Videos.”

Descriptive naturalism essentially explores the notion that photography can capture images perfectly without human error. It is the perfect blend of art and science.

In the first section of the exhibition, portraiture, landscape and architecture are explored as they would be seen in real life. Some pieces were slightly more artistic, such as Thomas Struth’s “Palmerston Place, Edinburgh,” a piece from the show that stood out for its crisp lines and high contrast.

Most pieces, however, looked at their subjects naturalistically, as they would have been seen at the time. This included work from famed landscape photographer Carleton E. Watkins, best known for his conservation photographs taken of Yosemite Valley.

The subsequent section on subjective naturalism, on the other hand, lent itself more to ambiguous forms and abstraction. Big names here included Edward Weston, Alfred Stieglitz and Ansel Adams.

A perfect example is Josef Auden’s “Sunday Afternoon on Kolin Island,” a photograph of maids working at what would appear to be some kind of lunch. The maids are captured from behind, whereas much of the first portion of the show featured traditional portraiture taken of subjects from the front. The maids are slightly blurred, but still recognizable. They are somewhat distorted but the piece as a whole is not entirely abstract.

Many of the other photos here included industrial subjects, which was fitting, as industrial and technological development contributed to the photographic progress.

The photos only continued to become more abstract as the show progressed, particularly in the experimental modernism segment, which allowed for and encouraged the avant-garde.

André Kertész’s “Paris 1929,” with its playfulness in capturing shadows, interesting angles and abstract composition, stood out as an experimental modernist work. The subject — the Eiffel Tower — is recognizable as a famed landmark, but is also presented in a nontraditional way.

Though there had been sprinklings of color throughout the show, in this portion viewers really got a taste of the abstract and the colorful with Barbara Kasten’s “Construct NYC,” a piece that the Vernons admired for its relation to European abstractionists, though their collection as a whole has more of a humanist core. The piece is a standout in its relatively larger size, interesting shapes and bright shades of pink and purple.

The portion on romantic modernism — which is inspired by nature, isolation and personal connectedness with the world — was the true highlight of the show.

Brett Weston’s “Reeds and Ponds” experimented with high contrast to the point where one might not recognize his work as a photograph. It was fascinating trying to figure out how he captured the image so exactly.

Speaking to connectedness to the world, or lack thereof, George Tice “Petit’s Mobil Station, Cherry Hill, New Jersey” was less abstract in form, but powerful in its exploration of the human experience. Reminiscent of David Hopper’s “Nighthawks,” Petit’s photograph tells a story of loneliness, one that sucks the viewer in with its pathos.

The end of the exhibition offered a camera obscura room where viewers could see images of LACMA’s surroundings (cars, apartment buildings, etc.) flipped upside down.

David Hockney’s “Seven Yorkshire Landscape Videos” concluded the exhibition, looking at nature on multiple screens using multiple cameras. It offered viewers a sense of resolution to photography’s story (up until now) as it looked at the extreme progress that has been made. From Talbot to Hockney, if you will.

It is important to note that a timeline with major events from the history of photography existed throughout the exhibition: Eadweard Muybridge motion studies (1878), Thomas Edison and W.K.L. Dickson develop 35 mm film (1889), Alan Turing develops Turing machine (1935), introduction of Adobe Photoshop and Internet (1990), are just a few of many examples.

This history expressed through the timeline and various genres within photography contributed to the viewer’s understanding of photography’s technical capabilities and aesthetic range. Together, it told a story of science and art, areas of study that perhaps are commonly thought of as disparate, but in the case of “See the Light,” are highly interconnected.

“See the Light” will be on display at LACMA through March 23, 2014.

Follow C. Molly on Twitter @cmollysmith