Los Angeles Plays Itself unveils unique look at the city

USC is located right in the movie capital of the world, Los Angeles and the presence of the prestigious USC School of Cinematic Arts only hammers home this point. With the nexus of the whole industry being here in Los Angeles, the city has been called the most photographed city in the world. But the relationship between the film industry and the city is more complex one than first meets the eye. The 2003 documentary Los Angeles Plays Itself examines that relationship in an exhaustive, relentless video essay comprised of hundreds of clips from movies based in Los Angeles, ranging from multi-million-dollar blockbusters to obscure C-movies. It is a must watch for any hardcore film fan, especially those who live and interact with Los Angeles on a daily basis, but until this week it has only been available to watch on bootlegged DVDs and grainy illegal streams online and at the occasional art house cinema generous enough to show it. On Tuesday, Oct. 21, it will finally be released on digitally remastered DVD, allowing it to reach a wide audience for the first time and pose to them the poignant questions it has been asking for a decade.

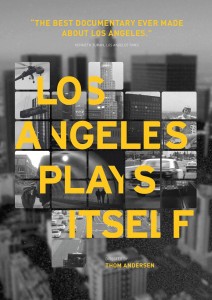

Passion project · Director Thom Andersen spent four years compiling and ordering more than 200 clips to create his almost three-hour opus, Los Angeles Plays Itself. The clips form a complex collage of the world’s film capital. – Courtesy of Cinema Guild

So, what took so long? The tangled web of copyright law was the culprit in this case. The film runs for a hefty 170 minutes and is almost entirely comprised of clips from commercially-produced motion pictures. The studios that produced these motion pictures typically employ teams of lawyers to dissect the use of any bit of their movies for potential copyright infringement. Despite this potential for disaster, the Cinema Guild took the plunge this year, and the DVD is primed for release without any rumblings from the studios that struck fear into the film’s creator Thom Andersen for so many years.

It was worth the wait. The film is a tour-de-force. The 200-plus clips flow effortlessly over Encke King’s narration as he covers topics as varied as architecture, geography and even the usage of the acronym “L.A.” instead of the words “Los Angeles.” When the film begins, the clips just start rolling by one after the other. There is little introduction, just a title card and the parade of clips, each accompanied by a small piece of white text declaring the clip’s film and year of release. It takes a little while to gain one’s bearings, as the stream is relentless. But once the viewer has gotten used to the breakneck rhythm of the film, its genius begins to become clear.

Andersen, who attended the USC School of Cinema-Television in the ’60s, spent four years putting together the clips for the exhaustive film, and the time invested shows throughout. Sure, the most iconic L.A. films — such as Chinatown, Blade Runner, and L.A. Confidential, appear in generous portions throughout, but just as much screen-time is dedicated to obscure films like Timestalkers and Out of Bounds. It gives the sense that Andersen left no stone unturned in his search to lift the mask that Hollywood has created for Los Angeles in the public consciousness.

In the opening portion of the film, King draws the parallel that while people look for narrative in documentaries, we should also look for documentary material in narrative fiction films. It is hard to do while watching one film because the director works so hard at navigating the viewer towards his intended path for the story, but, spliced up and overlaid like this, the way the settings have been used comes into much clearer focus. While watching Blade Runner, the Bradbury Building blends in as one of many shadowy sets in Ridley Scott’s dystopian vision for 2019 Los Angeles. But seeing the iconic building appear in 1940s noir pictures and 1980s lawyer flicks next to the futuristic Runner brings out information about Los Angeles from these films which the original directors could not have imagined their film’s contained.

The sheer variety of ways the same city has been depicted in film is mind-boggling, much so that it is difficult to picture the sheer scale of them. The city and its surrounding areas have been used to depict downtown Chicago, a lake in the Swiss Alps and rice fields in China. The terrain is so varied and the landmarks obscure enough that filmmakers have been able to use it for just about everything. As Andersen points out, however, this versatility has caused Los Angeles to almost appear as a generic city, since it has been used to depict so many other ones. This marginalization through overexposure is the weird contradiction at the center of Andersen’s argument. And it is the one he is combatting the most with his barrage of clips. Like a sort of flipbook, all the muddled depictions of the city blend together into a haze, and the common denominator uniting all the clips, Los Angeles. comes to the forefront. The city is the actual star of the film. Though King’s narration focuses on the city’s depictions — mostly negative observations — the city’s versatility as a character is what the viewer is left with, and this is the ultimate rabbit that Andersen pulled out of his hat with this manic symphony of a film.