Stonewall fails to capture historical significance

Roland Emmerich’s Stonewall is not about the Stonewall Riots.

The movie might claim to support LGBTQ rights, but does little to show this. At its core, this film is a campy take on a coming-of-age story of clean-cut, small-town boy Danny (Jeremy Irvine). Irvine, in this role, fails to captivate the audience. If possible, Irvine’s uninspiring performance makes the character even more unsympathetic and boring than the film’s writer, Jon Robin Baitz, probably intended.

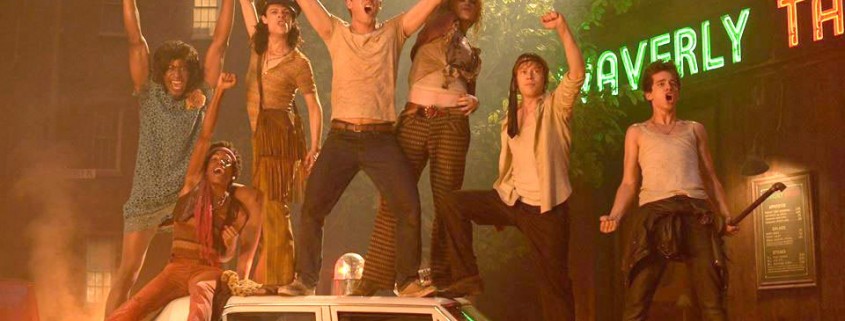

The story leads up to the revolutionary Stonewall riots, the historical demonstrations on June 28, 1969, which is often considered the catalyst for the gay liberation movement. Though the actual riots marked one of the most important events in LGBTQ history, Stonewall has one of the most treacle openers. Danny is emotionally abused by his crush, football star Joe Altman, played by an expressionless Karl Glusman. Then, Danny is thrown out after being caught in the act with Joe by his narrow-minded and angry football coach of a father, played by David Cubitt. In response, Danny decides to go to New York City, where he would have gone anyway because he coincidentally has a scholarship to Columbia University. Danny also has a spunky little sister whose role in this movie is trivialized because her sole purpose is to idolize Danny and ask him to get Andy Warhol’s signature.

While immersing himself in “colorful” city life, Danny meets a mature, older man, Trevor (Jonathan Rhys Meyers), who spends the entire movie trying desperately to smolder. He also hangs out with other diverse people, including Ray/Ramona (Jonny Beauchamp), a character partially inspired by transgender activist Sylvia Rivera. Ray’s huge crush on Danny is a recurring source of cruelty throughout the film. Danny’s rejection of Ray is the final blow. Ray is made into a perpetual victim who is obsessed with Danny’s All-American wholesomeness, The only other member of the group who is memorable is Cong, who has minimal lines and steals things. Everyone else, including famous gay liberation activist Marsha P. Johnson, is an afterthought.

There are several other things that are notably missing in this film. Respectful representations of the LGBTQ community and historical relevance are all lacking. In fact, it’s just plain hard to understand why Emmerich would fight so hard for this film. The sloppiness of Baitz’s writing is confusing. The subtext behind the script conveys the message that any LGBTQ person who is not white and doesn’t look conventionally male and straight is undesirable and frightening. The film also depicts trans-people as being obnoxious. The one lesbian character is portrayed as hysterical and undermining to the cause. When present, the other women in the film are static characters and seem to be uncomfortable with actually speaking. Gay men who are not Danny or his love interests are portrayed as disgusting and pathetic. There is an uneasy parallel in their attraction to Danny that is comparable to the way in which gay men were traditionally portrayed as fantasizing about straight men.

In short, Stonewall has managed to vilify the very thing that the film and the historical event itself were trying to glorify. Danny’s disdain and fear of people who are not white and gay is horrifying. Danny’s reluctance to be associated with anything in the movement, unless white men are involved, points to Emmerich’s whitewashing of this film. Even more uncomfortable is the fetishization of the non-white characters who aren’t gay in an “acceptable” way. Often Danny’s newfound friends are reduced to one-liners and flashes of flamboyant costume. This kind of treatment of characters is as callous as the cruelties that are dealt out by society.

This is by no means the only account of the actual events at Stonewall, but it is a high-profile film. With this, there comes a responsibility that comes with depicting a historical event that’s up there with Seneca Falls and Selma. This film, which set out to represent a moment of pride in the LGBTQ community, went so wrong. It narrowly focuses on the rights of white, gay, cisgender men. In one scene, Trevor makes Marsha P. Johnson move from the jukebox so he can change the song into his choice, “A Whiter Shade of Pale.” In the making of this film, transgender people were not only marginalized in front but also behind the camera. The blow is even harder because the film wraps itself in a blanket of good intentions. Hopefully, this movie will at least shed light on the systems of privilege and prejudice in the queer community. Ultimately, without the backdrop and name of Stonewall, this film would just be a mediocre teen movie.