LAPD terrorism prevention continues to be best medicine

In anonymous interviews last week, Los Angeles Police Department Metro Division insiders stated that the LAPD is not ready to respond to “terrorist-style attack[s]” because of a lack of training and proper equipment. An interviewee told NBC Los Angeles “maybe 10 percent” of the officers in the Metro Division, which handles crime suppression and counterterrorism, were ready to handle an attack. LAPD’s readiness was all “smoke and mirrors.”

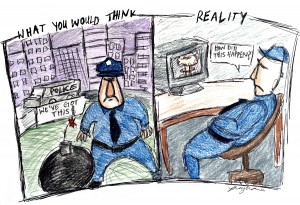

The story perpetuates the myth that the most effective response to terrorism is overwhelming police force. NBC has perpetuated a misunderstanding about terrorism that prevents citizens, and the governments that serve them, from effectively confronting the problem.

Terrorism is a tactic. Individuals and groups that are unhappy with governance structures and unable to seek political redress through legitimate channels use terrorism as a last resort to achieve their goals. Because of the power imbalance between the city of L.A., the state of California and the federal government, groups committing terror attacks do not seek direct confrontation with government forces. Attacks are designed to be carried out by few individuals, produce visible destruction and sow fear among Angelenos.

Put another way, a terror attack in L.A. won’t be Hans Gruber holding Nakatomi Plaza hostage, like in Die Hard. That’s too much of a direct confrontation. More likely are coordinated bombings, including small-scale attacks that capture media headlines, like the world has seen in much of Europe, the Middle East and Asia. Terrorists attempt to instill fear to force policy change, not to kill as many people as possible.

Because the goal of terrorists is not to directly fight government forces, a trained Metro Division cannot effectively stop terrorist violence. As Brian Michael Jenkins, an expert on terrorism and senior advisor to the president of the RAND Corporation told the Los Angeles Times in November, the majority of deaths in a terror event happen before the police can respond. Response, no matter how good, is not enough to seriously mitigate or stop a terrorist attack.

Instead, the best option for Los Angeles is to address grievances before they become plots and, barring that, for the LAPD to gather intelligence to stop plots before they are executed. Smartly, L.A. already does this: The LAPD Counter-Terrorism and Special Operations Bureau specifically meets with community leaders to hear and address constituent concerns. That kind of government response to localized or individual challenges in Los Angeles protects all of L.A. by eliminating political motivations for violence.

Nationally, the United States has begun to undertake these community-led softer approaches to stopping terrorist attacks. In a L.A. Times op-ed last year, President Barack Obama focused on community, noting that “community leaders from Los Angeles, Minneapolis and Boston [highlighted] innovative partnerships in their cities … helping empower communities to protect their loved ones from extremist ideologies.” These partnerships were part of a pilot program that the President had tasked the Department of Homeland Security with running to explore locally led efforts to confront extremism.

True, L.A. and the United States could be doing better to engage communities to stop terrorist violence. The L.A. branch of the Council on American-Islamic Relations noted soon after Obama’s op-ed appeared in the papers that the Islamic Shura Council of Southern California and the Muslim Student Association of the West Coast both opposed the narrow scope of current counterterror operations, which target and stereotype Muslim Americans. Terror is not limited to Muslims, as the recent attacks in Oregon demonstrate. In Los Angeles, stopping terrorism will require addressing political grievances in every community and group.