After the hit: How Jack Jablonski is living life to the fullest despite paralysis

It’s mid-afternoon on a Friday in the courtyard of the Troy East apartment complex — a block away from the USC campus — and Jack Jablonski is standing up.

He’s in the middle of a rehabilitation session and is strapped into equipment at his chest, waist and ankles, his arms resting on a tray protruding from a chest plate.

Getting to this point takes a lot of effort for Jablonski and his two trainers, Alicia Villarreal and Brent Brayshaw. They’ve moved him from his wheelchair to a massage table and stretched every part of his body from his shoulders to his Achilles vigorously for half an hour. Always sitting in a wheelchair means Jablonski’s muscles are tense.

They do this three times a week, two hours each session. Each day is a different focus, which can include standing, stretching, biking and core workouts. Today is Friday, so they stretch him, and they stretch him well.

“Today is ‘make everything hurt’ day,” Jablonski says, laying on the table while Brayshaw stretches his shoulders and Villarreal works on his knees, trying to stimulate blood flow. Vigorous is no hyperbole.

“Ready? One, two, three,” Brayshaw says as he moves Jablonski onto a seat on the equipment. He repeats it twice more, carefully shuffling the 6-foot-2-inch former hockey player’s body.

Finally, Jablonski’s there, standing on his own two feet. Still, he has to wait while they take his heart rate and blood pressure. If either is too high and he begins to feel lightheaded, he has to sit back down.

Today, everything’s fine, and Jablonski’s in his usual good mood.

“It feels nice to be taller than everybody,” Jablonski says. “I am 6-foot-2.”

***

Once upon a time, Jablonski was flying around hockey rinks.

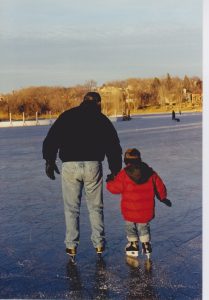

Jack Jablonski as a boy with his father, Mike. Jablonski learned to skate when he was three years old – Photo courtesy of the Jablonski family.

Growing up in Minnesota, Jablonski did what most kids did and learned how to skate at a young age. His dad, Mike, taught him when he was three, and then he picked up sports. He played baseball, tennis and golf — but nothing could beat hockey, the “bread-and-butter” sport of the state.

And he was good at it too, at the top of his class. He had a 50-goal season the year before high school for his Bantam-A team — an under-15 league — in a state that routinely produces the best young hockey players in the country. He dreamed of playing in the NHL and was on course to play for a Division I team in college.

“I had a passion for scoring goals,” Jablonski said. “And I was very good at it when I played.”

When he played. The use of past tense is striking and disheartening, a realization that the game he loved was tragically ripped away from him.

The date was Dec. 30, 2011. Jablonski was a sophomore in high school at Benilde-St. Margaret’s in St. Louis Park, Minn., playing in the championship game of a holiday tournament against rival Wayzata High School. His parents were in the stands.

The game was tied 2-2 with 14 minutes left in regulation. Jablonski had already scored a goal, and now it was getting intense.

“We were playing our rivals,” Jablonski said. “There was a lot on the line.”

Stepping out onto the ice, Jablonski took the puck in his defensive zone and skated up ice on a two-on-two. He moved past a defender and tried to head to the net but was cut off. So Jablonski turned away toward the boards, looking to pass. As he did, the player he just passed hit him in his right shoulder. Simultaneously, another defender who Jablonski didn’t see jammed his elbow into Jablonski’s neck, sending Jablonski face-first into the boards.

As Jablonski laid on the ice, his mom, Leslie, waited for him to get up. She hated seeing her son crash into the boards, but he always stood back up.

Jablonski plays in a high school game. His hockey career was tragically ended by a hit that paralyzed him – Photo courtesy of the Jablonski family.

“You start counting,” she said. “Get up; get up.”

But this time would be different. The arena fell silent. Panic settled in on everyone’s faces. Leslie was in shock. While Mike went to check on their son, she stayed behind, afraid of what she would find out. Finally, she went to him, and she heard the words that devastated her.

“He looked at me and said, ‘Mom, I can’t feel my legs,’” she said. “I almost keeled over on top of him.”

She remembers the desperation of the hours that followed: the trip to the hospital as she hung on to her son on a gurney, hearing that he might be paralyzed, that he might be a quadriplegic.

And she remembers when reality set in a couple of days later, standing next to her son’s bed at 2 a.m. as he turned to her.

“I’m paralyzed, aren’t I?” he asked his mom.

The question crushed her, as did her answer.

“Yes, Jack,” she said. “You are.”

The injury — a “complete injury” to Jablonski’s C5 and C6 vertebrae — severed everything in his neck vital for mobility and motion. All feeling below the level of injury was lost.

“You’ll be lucky to bend your right arm,” doctors told Jablonski. “Your left arm’s not going to move, really.”

“We told you that,” they added. “Prove us wrong.”

***

Within a week, Jablonski had already done it, able to attempt to slap his brother, Max. But there was so much more to that week, to the initial days that Jablonski laid in the hospital bed, his life forever altered.

Former hockey star Jeremy Roenick visits Jablonski in the hospital in the days following his injury. Roenick was just one of many visitors who lent their support to Jablonski. – Photo courtesy of the Jablonski family.

In Minnesota and across the country, his story blew up. He was all over the news, on the front page of Yahoo. A nonstop stream of family and friends stopped by to see him. Players from the Minnesota Wild — his hometown team — visited, as did other NHL teams when they stopped by to play against the Wild. His story even reached the upper echelon of hockey legends. Wayne Gretzky called. So did Bobby Orr. Jeremy Roenick changed his plans to fly to Minnesota.

The hockey community is very tightly knit, where everyone knows each other. And they united around the Jablonskis almost immediately, helping to fundraise to renovate the family’s house and purchase a van to accommodate Jablonski’s condition.

“A lot of hockey parents realized it could’ve been their child,” Leslie said. “Everyone just rallied around us.”

In turn, Jablonski remained upbeat. Strapped in a halo — a metal ring fixated around his head — he greeted every visitor with a smile, still making sure they were comfortable. He worried about how the guy who delivered the hit was feeling even though he was the one who was paralyzed (the player did visit Jablonski and received his forgiveness).

And as devastated as Leslie may have felt, she had no choice but to embrace her son’s attitude.

“To see your child laying in a hospital bed with a halo around head — he could’ve been so mad, but he wasn’t,” Leslie said. “The only thing we could do was join him and be positive. That became contagious. That’s why he is where he is today.”

The summer after his injury, Jablonski began setting goals for himself, for his recovery. His first one? Going back to high school as a junior. That summer, on top of four to five hours of intensive therapy a day for four to five days a week, Jablonski worked to catch up on all the classes he missed — and he did.

“That was a huge stepping stone, getting back to normality,” Jablonski said.

***

In 1981, former USC All-American swimmer Mike Nyeholt broke his neck in a motorcycle accident, leaving him a quadriplegic. That inspired Nyeholt’s former college roommate, Ron Orr, to start Swim With Mike, a scholarship program for physically challenged athletes. To date, the program, which pays full tuition, has raised more than $18 million and granted nearly 200 scholarships to students at 97 different universities.

And Swim With Mike found Jablonski, who learned about the scholarship when the Anaheim Ducks visited him in the hospital. From there, Orr met with Jablonski and his father and was sold by Jablonski’s character.

“Jack exemplifies what the scholarship was set up for,” Orr said. “The way he’s accepted his situation and lived with it and owned it. He’s mature beyond his age.”

Today, Jablonski is a sophomore at USC, majoring in communication and minoring in sports media studies. He is one of 12 Swim With Mike scholars at the University.

He chose USC after visiting his senior year of high school and falling in love with it. He loved the warm climate — Jablonski’s body can’t regulate body temperature, so his muscles would tighten up in the cold Minnesota winter. He loved the strong academics USC offered and the chance to live in the media capital of the world as a communication major.

And he’s taking advantage of these aspects. It’s been more than five years since the injury, and despite the crippling diagnosis, Jablonski is living college life to the fullest.

He goes to class like everyone else, getting around on a motorized wheelchair on his own. He can use his pinky finger to send texts, his hands to high-five or shake hands.

Still, there are limits the injury places on him: the mundane actions that can turn into challenges, whether it is opening doors, eating on his own, getting dressed or getting ready for bed.

“Spasms can kick my shoe off, or my foot can fall and I can’t always kick it up and put it up on my footrest,” Jablonski said. “My pants need adjusting or my shirt does. Whatever it is — daily, day-to-day living. Ninety-five percent of what the normal human does, I can’t do.”

Which is why Jablonski is grateful for the support system he has. A caretaker lives with him 24/7, catering to his needs. His second semester, Jablonski pledged the Tau Kappa Epsilon fraternity, linking him with 130 brothers to form a friend group and help him get through his days.

“If it wasn’t for TKE, I don’t know where I’d be,” he said. “I don’t know if I’d still be here just because of the friend group that I’ve developed.”

But Jablonski’s routine goes beyond his class and his fraternity. He just wrapped up his second season interning for the Los Angeles Kings — last year as a public relations intern and this year working for their communications team by hosting a postgame podcast. He is credentialed for every home game, watching from the press box.

“Never once did I want to leave the game after I was injured,” Jablonski said. “It just made me want to be with it more.”

Jablonski with Roenick. The two have bonded since Jablonski’s injury – Photo courtesy of the Jablonski family.

He also dedicates time to his foundation, the Jack Jablonski Bel13ve in Miracles Foundation (13 was his jersey number), a charity set up to support spinal cord injury recovery. Launched on the one-year anniversary of his injury, the foundation partners with the Mayo Clinic, one of the most reputable hospitals in the country. Last November, at a fundraising event during a Wild game, the foundation raised more than $350,000.

The money is being spent on research and studies by the Mayo Clinic that Jablonski hopes will one day cure spinal cord injuries. One possibility is what is called “epidural stimulation,” which Jablonski said is yielding results.

He is on a mission to see this through, much to his mom’s appreciation.

“Here he is, a college student, trying to stay in the game of hockey, going to school and class halfway across the country and still trying to stay involved to raise studies,” Leslie said. “It’s mind-boggling.”

If life were fair, Jack Jablonski would be playing hockey for a Division I program right now. If bad things didn’t happen to good people, Jablonski would still be flying around hockey rinks, scoring goals and celebrating with his teammates.

That’s the thing, though. Sometimes, your story is altered for some unknown reason, and how you write the rest is up to you.

For Leslie, not a day goes by that she wishes this had never happened to her son.

“You always wonder what life would be like otherwise,” she said.

But Jablonski has embraced what life has given him, and he’s not just putting on an act. He is honest about the journey he has taken and willing to discuss his traumatic injury to the point where he’s made jokes about it, according to Amy MacRae, a close friend.

“He’s very straightforward,” said MacRae, a sophomore majoring in journalism. “He knows his situation, and he doesn’t try to sugarcoat it.”

MacRae thinks Jablonski’s openness is one of his best attributes, allowing others in similar situations to look to connect with him and gain inspiration from him.

“He knows it’s horrible, but his life is still going to go on,” MacRae said. “His life’s not over. He’s still alive.”

Jablonski on a specialized bike as his trainers, Alicia Villarreal and Brent Brayshaw, look on – Katie Chin | Daily Trojan

Oh, he’s alive alright — more than just alive — and anyone who spends enough time with him can see the evidence. You see it in his determination, in his everglowing positivity that began from day one of the injury and is still emanating, bright as ever. You see it in his desire to remain invested in the game of hockey, in his foundation where he is using the fame and media attention to help not just himself, but also everyone affected by spinal cord injury. And you see it during his thrice-a-week rehab sessions, in the effort he puts in just to stand up and move his arms.

His arms have gotten stronger, his trainers say. And every time Leslie sees him, he looks “stronger and stronger.” Jablonski doesn’t doubt that he will walk again, but he knows the chances are slim. And yet, here he is, still fighting, still living, still dreaming. The blindside hit in a holiday tournament hockey game may have taken away Jablonski’s mobility, but it’s brought out the best in him.

“If there’s a good side to a tragedy,” Leslie said, “we’ve seen it.”