USC Libraries archive personal accounts during pandemic

Andy Rutkowski found himself on a deserted campus right before spring break. With classes temporarily moving online, students who would usually be studying for midterms in Doheny Memorial Library’s ornate halls and lugging their bags across campus, getting ready to leave for spring break, were nowhere to be seen. As Rutkowski, a visualization librarian, continued to visit the empty library with a few of his colleagues, he reflected upon the new normal; when USC transitioned online for the rest of the semester, he thought of the idea to create a space where the University community could come together to share their stories.

“The campus is usually abuzz right before spring break … all of a sudden it just switched to emptying out and being so quiet and it felt like a time to reflect, and it felt like a time to gather some thoughts and start sharing them,” Rutkowski said.

Rutkowski, along with his colleagues in Special Collections and University Archives, launched the #StayAtHome project in early April to gather the experiences of the USC and South Central communities as they adapted to remote working and staying indoors during the pandemic.

“When the pandemic started to arise and we started to feel the effects of this, people were asking ‘Has USC gone through something like this before?’” said Claude Zachary, a University archivist who helped jumpstart the project. “I realized the event that we’re going through is a once-in-a-lifetime — once-in-a-century-type situation, and it’s really important to try and document as best I can the effect that this has had on our community.”

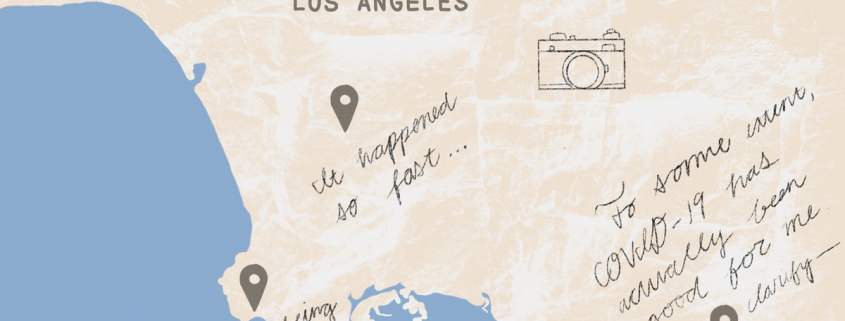

Initially, the project focused on collecting USC voices, but it expanded to preserve stories of the broader L.A. and Southern California area, with the city playing a significant role in the University’s history.

“Given the deep connections between the University and the city and the community, [their stories were] something that we didn’t want to leave out,” said Hugh McHarg, associate dean for strategic initiatives, who helped coordinate across library units to keep library priorities like regional history in mind. “If we had the capacity to preserve some of [these] stories to add to the history of the University and complement the history of our current experiences as a campus, we didn’t want to leave [them] out.”

Participants are able to submit material via an online form, in person or through mail as journals, blogs, photos, videos, social media posts and audio files. Submissions can also be in other languages, with the team currently working on translating the form into Spanish. The submission form also provides a list of suggested prompts for both the USC and L.A. communities for what their material can include such as “How has your campus involvement changed?” and “How do you keep in touch with friends and family?”

“The idea is to create a real rich body of documentation that illuminates people’s experience during this era of stay-at-home,” Zachary said. “A body of documentation that people could look at and come back to and reflect upon and hopefully help historians in the future have really firsthand experiences, [to] build an accurate and rich history.”

Participants also have the option to provide their general location to contribute to a virtual map — an idea spearheaded by Rutkowski after previously working on a mapping system as part of a microseminar and wanting to show the diverse range of places USC students were working from after returning home.

Wayne Shoaf, a metadata and digital librarian working on the #StayatHome project, decided to submit a letter he had written to his 98-year-old father — a personal piece about his life during the early stages of the pandemic. Through the letter, Shoaf wanted to tell his father the changes California’s stay-at-home period had on his daily routine working from home. He included a story about his experience visiting a grocery store where he and his wife were carded for their age before getting early access as citizens older than 65 years old.

“My basic idea in writing the letter to my father was that, first of all, he’s quite old,” Shoaf said. “He’s not as sharp as he used to be and I’m not real sure how much he really understands what’s going on around him, so I needed to put things into terms that he could sort of understand.”

Documenting his experience also helped Shoaf come up with the framework of questions people might be uncomfortable answering in their submissions and created the suggested prompts list. An anonymous feature was also added to allow people to share personal stories without having to identify themselves.

Shoaf also said reading about other people’s experiences working from home and the negative impacts on their life, such as financial issues, helped him realize his own privilege and think about the different ways people were affected by the pandemic.

“It’s been really reassuring to hear other people tell stories that are similar to mine so that I know that I’m not really the only one experiencing things the way that I’m experiencing,” Shoaf said. “Also to recognize that many more people have it more difficult than I do and I’m actually in a very lucky situation.”

To promote the project, Suzanne Noruschat, Southern California studies specialist at USC Libraries who collected submissions from the L.A. and South Central communities, said the team advertised the project through social media and the electronic mailing lists of organizations like L.A. as Subject, a research alliance that preserves and improves access to archival material of L.A.’s history. Rutkowski also reached out to students in an undergraduate writing course, introducing the project as an opportunity to reflect on the semester and share their personal stories with the USC community.

After Rutkowski introduced the #StayatHome project to her writing class, Qufei Wang decided to submit her experience as a graduating senior who was unable to say goodbye to her friends. In her submission, Wang also described the uncertainty and worry she faced with family back in China as coronavirus cases began to escalate in L.A., leading her to cancel her spring break travel plans to Hawaii.

Wang also said the project will allow the University administration to hear student voices and understand how they are dealing with online classes in order to create improvements and better resources in preparation of a potential future crisis.

“It’s good to know that there’s a way to record what people are going through,” Wang said. “You’re able to see the thoughts … [of] people who might share the same experience, who might resonate with you, [who] can also see what you experienced, what you would do.”

Noruschat said that along with collecting historical material, libraries were becoming more interested in documenting people’s personal accounts of life-changing events that would be of interest to researchers in the future. A previous project conducted by Special Collections had highlighted other significant events, such as the first L.A. Women’s March in 2017 — an event which has been documented each year via submissions of signs and clothing items from those who attend.

“This is a way to document history as it’s happening and to document it directly from the voices of people who are experiencing it,” Noruschat said. “I’m hoping that these materials will provide interesting and very vital and important documentation that [USC students, faculty and researchers] can access to discover and grapple with ‘What was this event? What and how were people experiencing this event?’ It could lead, in classrooms, for instance, to all kinds of interesting engagements with these materials.”

Shoaf said recent events and protests for Black Lives Matter had also prompted a discussion among the librarians to create another project to document protest stories, but nothing has been decided upon officially at the time of publication.

As community members continue to submit materials to the project, Zachary said the library would keep documenting stories to provide a collection of diverse experiences during the crisis as long as the pandemic continues affecting people’s lives.

“It’s become a common [phrase] for people to say ‘We’re all in this pandemic together’ — which, in some respect, is true. It is a global event,” McHarg said. “On the other hand, we’re not all experiencing it the same way, and it’s important to make sure that as an institution … we are collecting as diverse and inclusive set of stories as we can.”