Incoming Rossier dean transitions amid pandemic

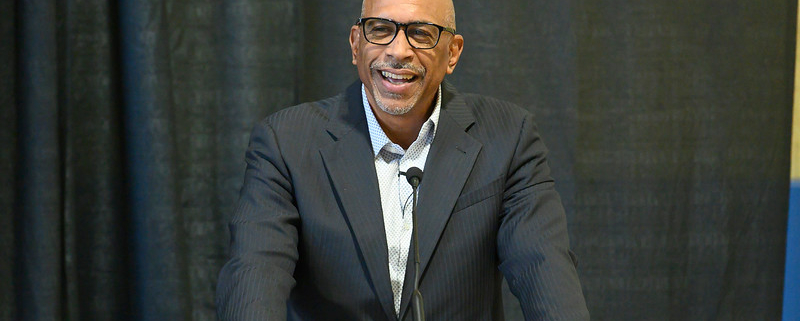

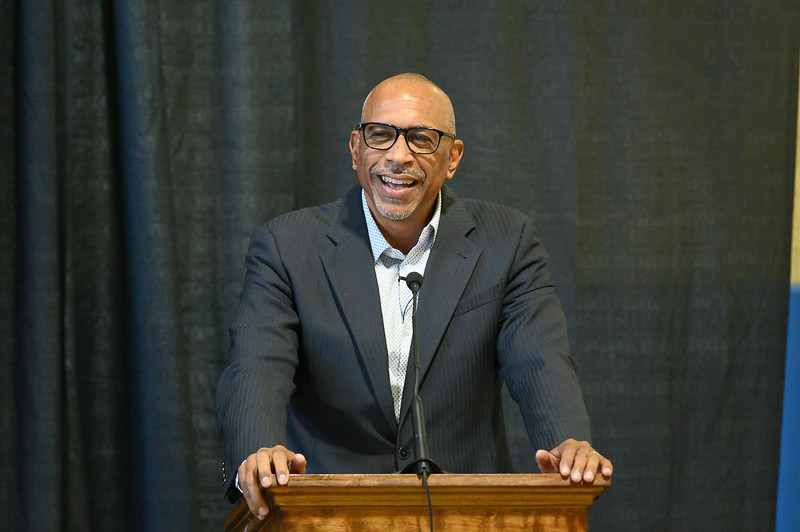

Instead of looking out the window of his new office in Waite Phillips Hall, incoming Rossier School of Education dean Pedro Noguera looks at the windows of Zoom calls on his computer screen. His days are full of virtual meetings rather than ones he can stroll to on the 229-acre University Park Campus, normally full of students whizzing by on bikes or eating lunch on McCarthy Quad.

When Noguera isn’t on Zoom, he and his spouse are homeschooling their 8-year-old daughter, making home-cooked meals or working on a podcast with longtime friends. Despite the coronavirus pandemic imposing changes to his personal and professional life, Noguera is making the most of his circumstances to prepare to take office across town by transitioning his projects at UCLA — calling attention to student homelessness and the school-to-prison pipeline — while learning the ropes of USC and coming up with solutions to safely bring students back to campus. Although the transition has proven to be challenging, one silver lining in working remotely is that there is no traffic, Noguera said.

“My work-from-home experience is probably just like everybody else’s,” Noguera said. “Both my wife and I work from home, and we keep [our daughter] busy with work and do things with her, but there are a lot of Zoom meetings.”

UCLA professor of education Tyrone Howard, one of Noguera’s friends involved in the education podcast focused on the effects social and economic conditions may have on schools, can attest to both Noguera’s lighthearted personality and his tireless work ethic. Twenty years prior, a nervous Howard approached Noguera at an American Educational Research Association conference to express his admiration for Noguera’s work. After Noguera’s warm response, the two have stayed in touch since then and now work together at UCLA, where Howard has witnessed Noguera’s growth throughout his career as an educator, researcher and leader.

“He is, in many people’s eyes, the foremost thinker on issues tied to education today,” Howard said. “He is someone who’s deeply committed to equity and access in schools for all children, someone who’s a tireless advocate for marginalized, Black, brown, poor children. He’s well respected internationally. He’s a consensus builder … He’s a visionary but he doesn’t stay at the visionary stage. He puts in the time to execute plans of action to help those ideas come to fruition.”

After more than 30 years working in education — from professorships at prestigious institutions, including Harvard University and New York University, to teaching at public schools in Rhode Island and California — Noguera will join USC July 1 as the Rossier dean. Drawing from his personal experience as a student, teacher and researcher, Noguera looks to solve inequalities in classrooms by advancing scholarship that not only examines the social causes of these gaps but also enacts solutions to close them.

Coming into his own

Coming from a working class family, Noguera knew the importance of education but never thought he’d work in it.

A New York native, Noguera’s parents did not graduate high school. As a first-generation college student at Brown University, Pedro Noguera earned his bachelor’s degrees in sociology and American history, later completing a master’s degree in sociology from Brown University and a doctorate in sociology from the University of California, Berkeley. However, his academic accomplishments came with obstacles along the way.

“As an undergrad, the main issues were feeling as though I didn’t fit in, feeling as though I didn’t fully belong,” Noguera said. “Over time, even during my first year, I started to feel more comfortable. I started to see how my background provides me with strength like knowing how to work hard and deal with people, so I was able to overcome my feelings of intimidation.”

Fortunately, he found a mentor, sociologist Martin Martel, who appreciated his tenacity for asking questions in class. Noguera often joined Martel during his office hours to read advanced sociology material. Martel helped Noguera turn adversity into opportunity by notifying him of grants and scholarships and encouraging him to pursue graduate studies in sociology.

“So many times, especially for first generation college students, college is a big mystery, like what opportunities are available for funding, but he played that role [as a mentor] and then encouraged me to apply to graduate school,” Noguera said.

As an undergraduate student, Noguera also earned his teaching credential in social studies to fall back on teaching jobs, though he didn’t intend to pursue a career in education at the time. Later, as a doctoral student studying sociology at UC Berkeley, Noguera became a substitute teacher for public schools in Oakland, where he lived in a storefront apartment. As he spent more time in K-12 education, he found a connection between his studies in sociology and education.

“I thought substitute teaching was a very good way to learn about the community that I was living in,” Noguera said. “It was also a great way to do something that I felt was practical and impactful. Grad school didn’t feel like that at all, at times it felt very alienating. Being in schools and teaching had the opposite effect.”

Despite having taught thousands of students from preschool through high school, there is one student Noguera will never forget. While a professor of education at UC Berkeley, Noguera volunteered to teach at a continuation school for students who had been expelled from their original schools. One day, one of the students showed Noguera and the principal his car. The trunk was filled with weapons.

“I had a student who was kind of a leader among his peers and who was very smart, but he was involved in some criminal activity,” Noguera said. “And one day, he came to see me and the principal and told us that he had been shot at and that his brother’s been hit by bullets, and that he wanted to get revenge … He was going to go and get the people who shot them.”

The principal and Noguera spent several hours explaining to the student why retaliation was not the best course of action. Afterwards, they realized that if the student did not retaliate, he would likely face more danger. From there, they helped the student enroll into the military.

“The irony was, he’d be safer in the military, even at a time when we were going to war — the first Iraq War — than he would be living on the streets of Oakland,” Noguera said. “Those were the kind of difficult issues that many of our students were dealing with. To be a teacher in that context meant you had to deal with those issues, you couldn’t just tell a student to be safe, you had to understand what contributed to their lack of safety.”

These experiences not only motivated Noguera’s research on equity in education but it also helped him in his role as an educator to not only deal with issues concerning student safety but also understanding the factors contributing to that lack of safety.

“It reinforced my sense that for schools to make a difference for kids, schools have to understand what was happening in the lives of kids, they had to be responsive to their needs,” Noguera said. “And to the degree that they could do that, then schools could become powerful.”

A journey in academia

Noguera began his career in academia at UC Berkeley as a professor of education and director of the Institute for the Study of Social Change. From there, he became a professor of communities and schools at Harvard University before accepting a position as a professor of education at New York University, where he also served as executive director of the Metropolitan Center for Research on Equity and Transformation of Schools.

When then-Harvard professor of education Suárez-Orozco was giving guest lectures at UC Berkeley, he was asked by a Harvard committee to look into recruiting Noguera, teaching at UC Berkeley at the time, to join the Harvard education faculty. From there, the two colleagues would continue to work together at Harvard, New York University and UCLA.

“At UCLA, he’s been an exemplary citizen of the university, willing to step in, roll up his sleeves and get to work, Suárez-Orozco said. “He’s a fine, fine teacher. He has been a trusted friend in the long run … The word we use in Brooklyn, New York is he’s an all purpose mensch … it’s a very New York term for a very wonderful person.”

Later, after joining UCLA’s faculty as a professor at the Graduate School of Education and Information Studies in 2015, Noguera founded UCLA’s Center for the Transformation of Schools, an education research center of UCLA professors and doctoral students primarily dedicated to studying the effect of the school-to-prison pipeline on Black students. From his experiences growing up, Noguera was determined to help marginalized students in his career.

Through the center, Noguera led his team in conducting case studies on funding distribution, social and emotional learning and new discipline policies for school districts including the Pomona Unified School District and the San Diego Unified School District. Noguera’s successor as director of the center, Howard, who witnessed the impact of Noguera’s research on policy. However, the center’s work doesn’t end at the district level.

One policy recommendation Noguera has championed is the adoption of restorative practices in school districts. In an effort to reduce student suspensions, discipline policies have altered from banning students from attending school to instead keeping them in school. The time wasted by going home and learning nothing is used for students to take responsibility and repair relationships with peers and staff, addressing behavioral problems directly rather than hoping that students will change their behavior by themselves.

“Research can sometimes be helpful in provoking change,” Noguera said. “For example, we released a study on homeless students in California [where we] wanted to really show how so many kids were rendered invisible because no one was even aware that they were homeless, and a lot of times, those kids don’t have adequate services. So, doing work like that is a way to draw attention to problems.”

Adapting to crisis

The search process for a new Rossier dean began in August, with hundreds of candidates applying to the position. From his experience as a teacher in addition to his membership of various school boards and board of trustees and advising government officials on school system policies, Noguera seemed like the perfect choice.

“He’s a world-class scholar … Not only does he do work at the highest level of pure scholarship, but he also has a tremendous understanding and impact in practice,” said John Matsusaka, Marshall School of Business professor and executive director of the Initiative and Referendum Institute. “He’s really an electrifying candidate for a school that’s been at state leadership for 20 years. It’s going to be fantastic to see what energy he brings on the next page.”

With the possibility of classes continuing online in some form in the fall, Julia Marsh, a professor of education at Rossier and one of several faculty members on the search committee for the dean position, said Noguera may face technical challenges coming into the position during the coronavirus pandemic, such as balancing the Rossier budget or phasing students into campus physically. However, she remains optimistic that he will be able to overcome the obstacles with his experience.

“[It’s] a difficult time for someone to come on and take on leadership in a new way,” Marsh said. “I think he brings skills and experience that can lead us during this difficult time … You can tell that he’s someone who values relationships, human capital and building values. People [at Rossier] are really excited about him coming.”

As a frequent adviser to the superintendent of the Los Angeles Unified School District since his time at UCLA, Noguera also said that Rossier should act as a thought partner for school systems and strengthen the relationship between USC and the local community. As primary and secondary schools approach the challenge of reopening while maintaining modifications for social distancing, Noguera intends for Rossier to be an ally to local schools by using the school’s research capabilities and implementing programs.

“[The pandemic] has exposed our inequities in societies — there are so many families that are struggling now financially … that weighs on me,” Noguera said. “But on top of that, from an education standpoint, we know there are a lot of kids who haven’t been able to participate in distance learning because they don’t have internet access.”

While school systems could not have foreseen the necessity for remote learning, Noguera said he believes more progress should be made to ensure that students are offered a stimulating environment similar to what they would have had in an in-person classroom — starting with providing internet access for students in need.

“We should first of all acknowledge that there were problems with the way we were doing things, especially in education before, and this should give us a chance to do things differently,” Noguera said. “I would like to see Rossier become a leading center for innovation in education where people could get support in thinking through these new approaches.”

Though the future of education at USC is uncertain due to the pandemic, Howard, Marsh, Matsusaka and Suárez-Orozco said they are certain about Noguera’s capabilities to lead Rossier moving forward.

“I’m excited about the potential collaboration between USC and UCLA,” Howard said. “I think there’s always room for that. I think his being [at USC], that’s only going to be a win for Los Angeles schools, children and families.”