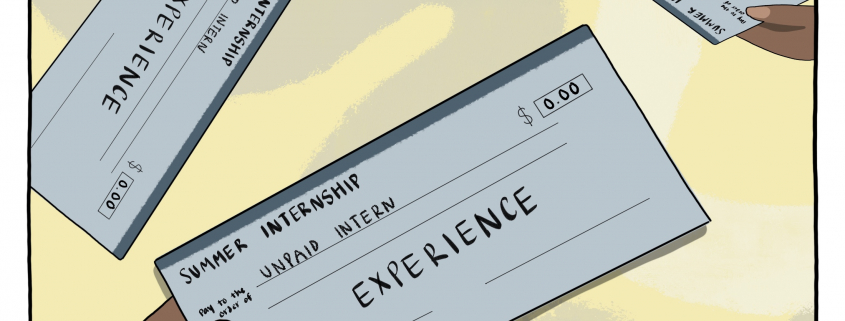

Unpaid internships perpetuate inequality

After weeks of protests spanning the globe in support of the Black Lives Matter movement, USC, along with other institutions, has received public pressure to reexamine its more-than-centurylong complacency in systemic racism and inequality. As the school hopefully ascends into a new era in which it actively looks to support marginalized students, it is essential to address one of the starkest examples of disparity within the college community: unpaid internships.

Although USC has scholarship programs to support students who cannot afford to take an unpaid internship, these funds are awarded to an extremely small pool of applicants and offer only a small stipend that is insufficient for students looking to support themselves. To better address the issues of unpaid internships, USC needs to expand these programs to more students and increase the stipend.

While abolishing unpaid internships would eradicate this inequality, it’s unlikely to happen anytime soon. Keeping that in mind, a way to bridge this gap is for institutions like USC to offer resources that allow students, regardless of socioeconomic status, to build their resumes and skills.

The Economic Policy Institute reported in 2019 that white families have a median household wealth 12 times higher than that of Black families. This discrepancy is the result of centuries of discriminatory practices, such as redlining, that have prevented Black families from accumulating wealth.

Redlining was a practice that began in the 1930s in which banks denied loans to people of color in an effort to stop them from buying homes in predominantly white and wealthy neighborhoods. Home ownership is a passive way to accumulate wealth over generations and these practices put people of color, Black people in particular, at a severe disadvantage when it came to increasing household wealth — the very wealth needed to subsidize a student working all summer for an internship that pays nothing.

An unpaid internship may offer a student needed job experience, but it assumes the student does not need to prioritize earning an income, thereby reinforcing centuries of inequality and discrimination that disproportionately benefit white families. As a result of these discriminatory practices, affluent students benefit from the current system at the expense of others.

Considering that around half of all graduating seniors participate in an unpaid internship, there is no doubt that work without pay is not only common for college students but somewhat expected.

Unpaid internships offer students an opportunity to learn and refine their skills as they bolster their resume. This gives students who can complete unpaid internships a leg up in the competitive college environment. According to a survey by ProPublica, 60% of employers preferred to hire applicants with internships on their resume.

For students in fields like journalism, nonprofits or political science, unpaid internships are particularly common, presenting the dilemma between a retail job that pays or an unpaid internship that looks impressive on a resume.

In turn, predominately white, affluent families that can afford unpaid internships often benefit long-term by securing jobs post-graduation over other students — particularly students of color, who often could not afford to work for free — further perpetuating a cycle of inequality.

In response to this problem, USC has offered scholarships to allow students to pursue unpaid internships. The USC Dreams Dollars Scholarship offers $1,500 to a few outstanding students who have secured nonprofit or government unpaid internships for the summer. In 2018, however, this scholarship was awarded to only 10 students, hardly making it an accessible or realistic option for many students. In fact, in 11 years, just 115 Trojans have received this scholarship.

USC has an undergraduate population of 20,500 students — 4.9% of whom fall in the bottom 20% of the tax bracket, equating to just over 1,000 students from families who make less than $20,000 each year. If even one-tenth of these students wished to secure an unpaid internship over the summer, they could not comfortably do so, given the probability they will not receive the scholarship.

Additionally, USC offers a scholarship that awards $2,000 to first-generation college students. A $2,000 stipend equates to $5 an hour for an internship that lasts 10 weeks for 40 hours a week.

These scholarships are a step in the right direction, but they do not address the full scope of inequalities reinforced by unpaid internships in the most meaningful or supportive way. Awarding $1,500 and $2,000 is a start, but it’s not enough for students who rely on the stipend for housing, food and other expenses over the summer. In an effort to combat systemic inequalities, not only should USC award more students with scholarships for unpaid internships, but it also must increase the funding for each.