The Left and the Left Out: A binary choice is no choice at all

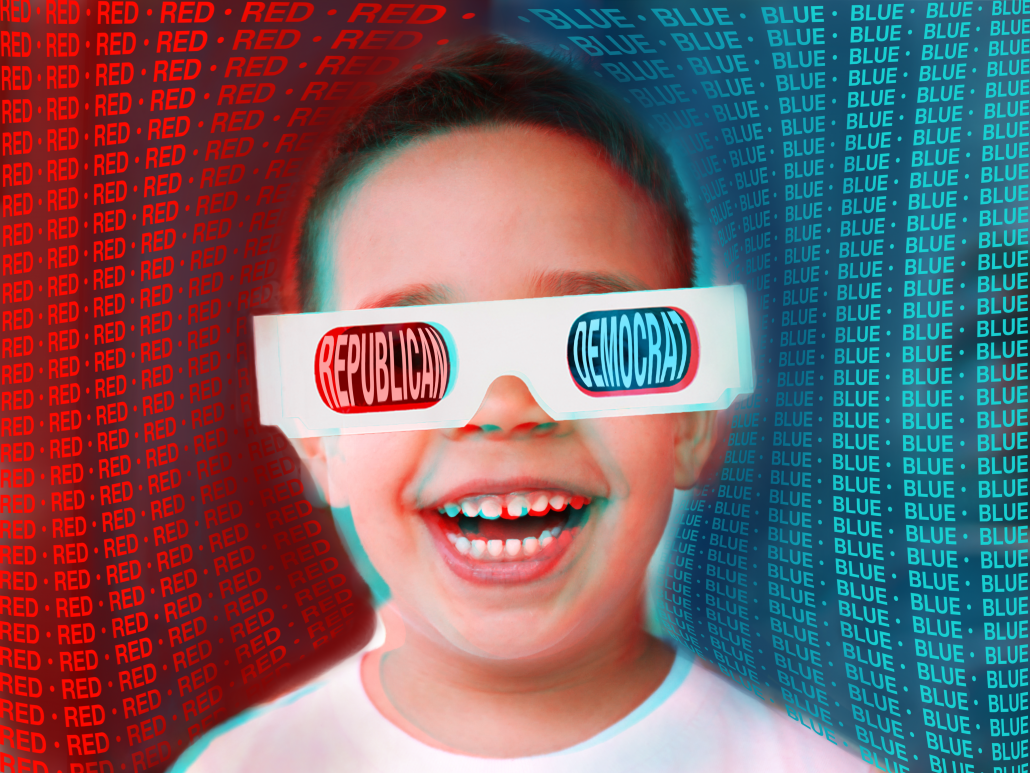

Plunge into a nostalgia-tinted trip, if you will, to experience the wonders of IMAX 3D and ICEE-induced brain freeze. As the lights dim, you throw the cardboard frames you were handed at the door over your eyes. Close one eye and the world turns red, the other and it turns blue — or take the glasses off, and the illusion of 3D gives way to eclectic chaos.

American politics is a messy affair — in many ways, it resembles a 3D screen without glasses. Issues are abundant in their quantity and complexity, and yet we are not only told to look at them through a red or blue binary but to etch that view into our identity. Our choice will inform the media we consume and the people we surround ourselves with, so choose wisely.

Of course, this is a simplistic picture that does not quite capture the nuanced identities within each party, ranging from revolutionary idealism to pragmatic realism on the left and from a measured brake to a militaristic backlash on the right. Reactionary politics suggests an inevitable pendulum swing from left to right, with the moderacy or extremism of each swing determined by the urgency of the moment. But is a pendulum swing truly inevitable?

Constituencies have diverse needs, so competition between them is certain. However, it is reductionist to suggest constituencies are so homogeneous that they can only be serviced by one ideology. How else can we explain over a million Sen. Bernie Sanders supporters voting for former President Donald Trump in 2016? Our understanding of a linear left-to-right political spectrum seems incomplete. Coalitions do not necessarily split at the center of the political spectrum and swing voters are not exclusively moderates.

So, why only have two major parties? Wouldn’t the American people benefit from more options? What even are parties and what do they do?

In their theoretical essence, political parties are a loophole to the Constitution’s system of checks and balances. The Founding Fathers sought to distribute power by creating three “co-equal” and separate branches — one to create, one to execute and one to interpret laws. None with the power to do all three.

Enter political parties. Through coalitions, interested politicians realized they could sidestep the checks and balances and control all levers of government. One central organization could finance campaigns for congressmen and presidents that could appoint ideologically aligned judges once elected.

In modern times, the financing both parties amass is staggering, all but curtailing the competitive ability of independents. This is especially true for the highest offices in the nation, where even the most successful independent candidates (such as Sanders) align themselves with a party to have a shot.

How else could they compete? In the 2020 presidential election, Democrats spent $6.9 billion overall, while Republicans spent $3.8 billion on a single candidate. But joining a party is a prerequisite, not a guarantee for competing — barriers to entry do not end there. In February 2020, none of the seven presidential candidates remaining could be categorized as “ordinary” Americans. Two were billionaires, four were millionaires and the last was a Harvard alumnus.

The two parties dominate down-the-ballot races, as they play a numbers game to attain a majority. In districts deemed “safe,” party recognition alone should be enough to carry a candidate to victory. The other party might not even go through the trouble of nominating a candidate. In the most contentious districts, both parties spend billions to maximize competitiveness. In all instances, independents face steep uphill battles.

Federal spending is allocated to political parties every year further tilting the slopes. Consider the 2020 election, where total federal spending on presidential campaigns was over $6 billion, and total federal spending on congressional campaigns was over $7 billion. In our twisted reality, tax payers surrender their self-determination to political parties who they pay to prescribe them their candidates.

Political parties do their part, deciding who can run for office and who cannot. Their decisions take into consideration a candidate’s electability and background but only once party loyalty is ensured. Like movie producers casting actors, political parties “cast” candidates.

Nothing maximizes winning probability like a good narrative. Like writers, parties weave fiction and nonfiction into elaborate tales propagated to their followers. Seeing the world in red or blue, the American public becomes ever more polarized, and American democracy ever more unstable. If the election were stolen by blood-sucking pedophiles, would you storm the Capitol gates?

In a time before political parties, our first president warned a young nation. “[In] the course of time and things,” George Washington foretold that political parties would “become potent engines, by which cunning, ambitious, and unprincipled men will be enabled to subvert the power of the people and to usurp for themselves the reins of government.” After more than 200 years of reification, we have come to accept parties as natural realities of American life.

Does politics in the land of “opportunity” provide anyone any such thing? Or is power static, festering in the same circles?

In 2021, cynicism remains on the rise. A year ago, when voter turnout reached a 120-year high, 33.7% of eligible voters still chose not to participate. The remaining 66.3% became ever more polarized, while politicians played with fire for personal gain. Is it time to re-imagine the two-party system?

Take off the glasses, America.

Javier Calleja Erdmann is a junior writing about politics. His column, “The Left and the Left Out,” ran every other Wednesday.

The article was updated to credit Alyssa Shao as the designer.