USC must consider building a skatepark

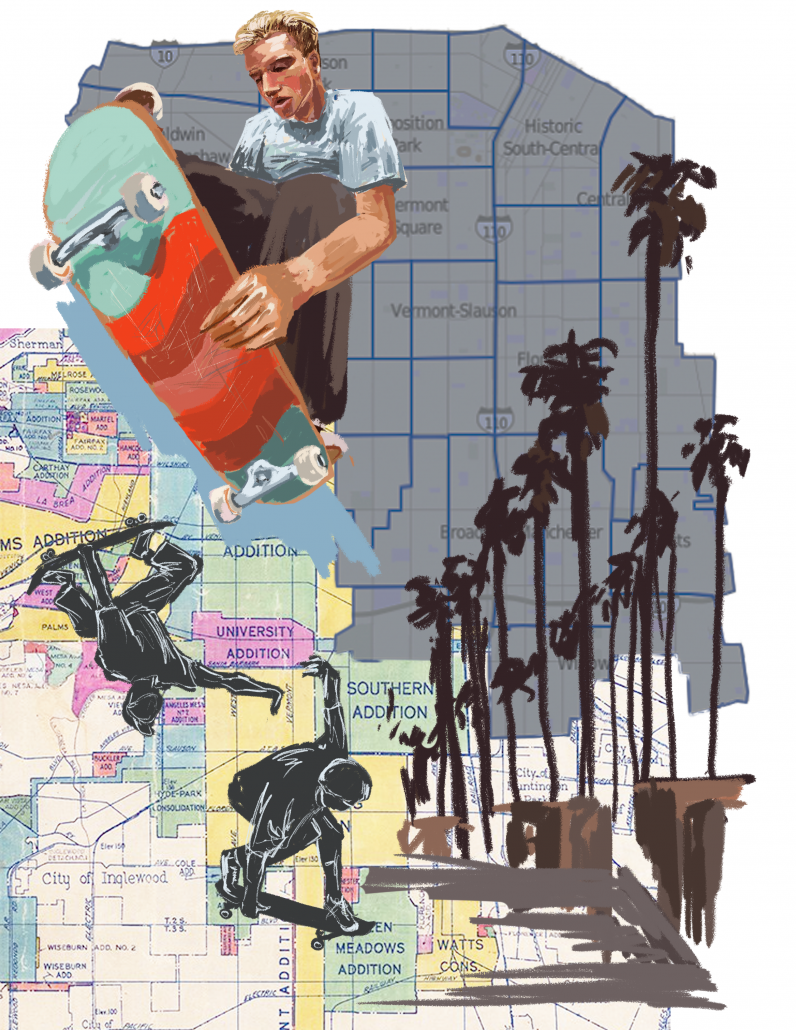

“Skate and destroy” is a phrase from the popular skateboarding magazine “Thrasher.” It represents the spirit of skateboarding and perseverance against self-imposed obstacles that skateboarders find in the most unthinkable places.

However, “skate and destroy” seems to have been taken seriously by those on the periphery of skate culture. Anti-skate devices and architecture are very real and often go unnoticed by those outside of the skating community. They can be as simple as tiled or brick sidewalks, or as obvious as metal pegs — which skaters colloquially call “skate stoppers” — on the edges of benches and ledges.

USC has incorporated some of these elements into their own architecture and has long policed the sport. For example, across the street from the Hoover and Jefferson entrance to USC is a famous skate spot called the “Block.”

In order to discourage skaters from doing tricks on the ledges, USC introduced sections of loose gravel and dirt directly around them. The spot still remains popular and many professional skaters, such as Ishod Wair, have recently skated the ledges. However, when these lengths are taken to stop skaters, the message is clear: Skaters from the surrounding community are not welcome.

When you take into account the small amount of recreational areas and green spaces in the surrounding community, that leaves virtually nowhere to skateboard. However, things could change. Now that skateboarding is in the Olympics, the University has an opportunity to further legitimize the sport in mainstream culture and reconcile its relationship with the skaters in the surrounding community of South Central.

Brian Wood, who started skating in 1977 at the age of seven, frequents the Exposition Park Rose Garden, a popular skate spot that hugs the outer edge of USC. For Wood, skateboarding changed his life and allowed him to meet thousands of people from all corners of the world. In Wood’s opinion, it’s not even a question: USC needs to make a skatepark.

“The University is considered the brain of the society so everything that goes on through the society goes on through the University,” Wood said. “If you can have a field, you could also have a skatepark.”

That skatepark could provide a safe space for everyone in the community to skate. There are only three skateparks around the USC area and the closest one, Gilbert Lindsay Skatepark, is about two miles away from the school. A skatepark at USC would not only be convenient but also a center for the community. It would transform the University from a bloated imposition to a part of the surrounding landscape.

“USC is in a really unique position because of its location within the community,” Wood said. “You see how many people are here regularly skateboarding just across the street on the other side of the blocks, so they’re obviously coming from the surrounding communities so they could definitely do a lot to transition that through the skateboarding.”

Camo Jorel has been skating for about 20 years and also frequents the skate spot at Expo Park. For Jorel, a skatepark at USC would create a place for skaters to hang out and have fun. Furthermore, a skate team at USC would represent something else entirely.

“What it would do for the people is you can literally see somebody who was born here, get out of here, make it, become something, which would inspire other people from the neighborhood,” Jorel said. “We come from a neighborhood where nobody makes it out. What makes you think you’re gonna make it out? So, the more things you have to get good at like skateboarding, that will be just another way for people to make it out of this situation.”

A skateboarding team would be a new opportunity for kids in the South Central community. They would be able to use their talent on the board as a way to gain access to the financially inaccessible USC. It would also be an opportunity for kids to realize their dreams to become a professional skater. If USC has a football team, a basketball team and a rowing team, then it can make room for a skateboarding team.

Establishing this sort of competition on a university-level would not be difficult for USC, an institution that not only has resources that can be reallocated to create skateboarding facilities but also a large surrounding community where skateboarding is integral to its culture.

Ultimately, we need to stop suppressing skate culture. Let the youth skate and destroy. Let the youth have a space to have fun without being policed and harassed. While USC students are allowed to skate to class, South Central skaters are not given the same privilege. USC’s stance on skateboarding should be the same across the board: Either everyone is allowed to skate or no one is. The correct thing to do is the former.

Brian’s son, Taj, is a nine-year-old skater who has been skating since he was a one-year-old. If USC was to have a team, Taj said he hopes to skate in the street competition.

For a kid like Taj, a skatepark would be a place where he could explore the sport and culture of skateboarding safely and comfortably.

“It shouldn’t just be to college students, it should be to everyone,” Taj said. “it should be open to everyone.”