USC to posthumously honor Nisei alums

After majoring in business at USC during the early 1940s, Jiro Oishi spent the rest of his life returning to campus for game days, dressed up in cardinal and gold.

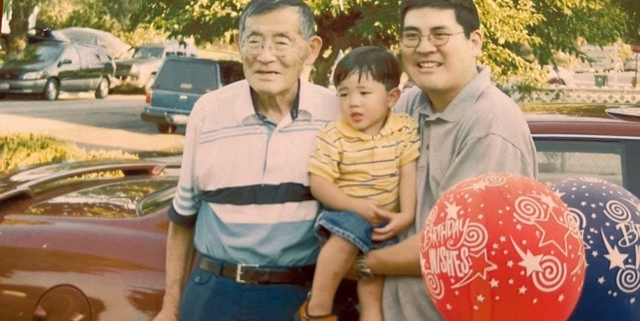

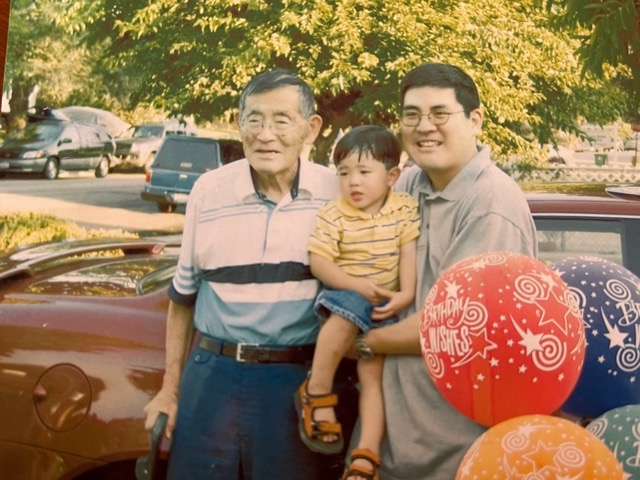

According to Oishi’s daughter, Joanne Kumamoto, her father was a Trojan “‘til the very end,” keeping up with University athletics and forever eager to take a jab at UCLA. Every year before he passed away in 2002, Oishi and his college roommate bought season tickets to USC football and basketball games.

Throughout her childhood, Kumamoto said she believed her father had a degree from USC — in part because he always seemed so proud that he’d attended the University. Kumamoto didn’t learn the truth until she was nearly finished with high school: The University had never let her father graduate.

After Japan bombed Pearl Harbor in December 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, which commanded the internment of approximately 120,000 Japanese Americans and nationals living on the West Coast. Oishi and 120 other first-generation Japanese American “Nisei” students studying at USC were forced off campus and into internment camps for the next three years.

Following World War II and the closure of internment camps, former USC President Rufus B. von KleinSmid refused to re-admit the Nisei students who were previously enrolled at the University. When the students found other colleges willing to admit them, von KleinSmid then refused to forward their transcripts that were required to transfer course credits, stating that to do so would be “aiding and abetting the enemy.” As a result, many Nisei students were forced to start over as freshmen at different colleges, and others had no choice but to end their education without a degree.

In May 2022, President Carol Folt will recognize Kumamoto and other Nisei descendants at the University’s spring commencement ceremony. USC will also issue a formal apology and confer posthumous honorary degrees to the 121 Nisei students at the Asian Pacific Alumni Association gala in April.

Kumamoto said she was “happy” that the school was taking the steps to make amends but wishes it could have “been done earlier” so that her father could be there to see it himself.

“The timing on this was just not for our family. I mean, my father was sick and he had cancer and he passed away earlier,” Kumamoto said. “He had always hoped that the school would recognize their decision to not help [the Nisei students].”

Jonathan Kaji, former APAA president, is also helping the University in the search for students’ descendants. In 2007, Kaji and professor Lon Kurashige began advocating for USC to offer a form of restitution to the Nisei students and their families. The two were able to get the University to agree to grant the Nisei honorary alumni status as well as issue honorary degrees to the students who were still alive. However, it took nearly 15 years to persuade the USC Board of Trustees and a sitting President of the University to agree to the formal apology and posthumous honorary degrees.

Kaji said one of the biggest reasons he didn’t give up the cause was because he made a promise to his parents, who have since passed away, and “to do the best job” he could to have the University acknowledge the harm it caused the Nisei students. Although Kaji’s parents attended USC after the war, Kaji said they were friends with older Nisei students who were denied their transcripts and degrees.

“To look at these old photos of the Trojan Japanese Club, when all these students were in their late teens, early 20s, and suddenly, after 80 years, be confronted with what they experienced, it made it a personal campaign,” Kaji said. “It wasn’t simply some faces in black and white from 70, 80 years ago — these were people that I knew, but I had no idea that they experienced this.”

In February 2020, law students Mirelle Raza, Sara Zollner and Jenna Edzant met Kaji while they worked on a research project about the University’s treatment of the Nisei students during and after the war. Following Folt’s announcement that the University would remove von KleinSmid’s name from the Dr. Joseph Medicine Crow Center for International and Public Affairs building because of his history of antisemitism and public support of eugenics, Edzant, Raza and Zollner contacted the nomenclature committee, asking to rename the building after Kaji’s father, Bruce, who dedicated much of his life to advocating for racial equality.

On Thursday, Folt announced that the University had selected a different candidate — USC alumnus and Native American historian Joseph Medicine Crow — for the new name of the center.

In an email to the Daily Trojan, Paula Cannon, the co-chair of the CIPA Naming Committee, wrote that Bruce Kaji was one among 200 other candidates considered for the new name of the building.

“I wish we could have recognized so many of these incredible people,” Cannon wrote. “I hope that the name we finally did select in Joseph Medicine Crow will be seen as equally deserving as so many of these alums, including Bruce Kaji and the important work that he did.”

Moving forward, Edzant, Raza and Zollner are interested in ensuring legacy status for the descendants of the Nisei students, given that certain scholarships at the University are only available to relatives of alumni.

According to a Nov. 22 statement to the Daily Trojan from Dean of Admission Timothy Brunold, legacy students, or “scions,” are defined as “individuals with a direct relative who attended the university. That could include a sibling, grandparent, great-grandparent, or great-great grandparent.” Brunold also wrote that “if an applicant lists a direct relative as having attended the university, the applicant would be granted scion status. This would include descendants of Nisei students.”

For Kurashige, a professor of history and spatial sciences, he hopes to see USC open the University archives to allow the public access to von KleinSmid’s papers on Japanese internment from the 1940s.

“USC doesn’t show the presidential papers to anybody,” Kurashige said. “I mean, they really shut it down whereas other schools’ presidential papers are completely open — especially public schools, but even private schools like Brown.”

In an email to the Daily Trojan, University Archivist Claude Zachary wrote that it is unclear whether or not the von KleinSmid papers still exist. When he arrived at USC 23 years ago, the papers were missing and nobody gave him a definitive explanation of their disappearance, Zachary said.

When contacted about the posthumous degrees and the status of the von KleinSmid papers, the president’s office declined to provide a comment to the Daily Trojan.

Editor’s note: This article was updated on Dec. 14 at 7:07 p.m. to reflect that legacy students are defined as individuals with a direct relative who attended the University.