Due Process: A look at USC’s sexual assault culture

Content warning: This article contains references to sexual assault.

Disclaimer: All names in this article have been replaced with pseudonyms per the request of sources to protect their identity and privacy.

It was Riley’s first day of class in Spring 2018 when her professor asked her out to dinner. Then a sophomore, the 2020 graduate thought the academic she looked up to wanted to discuss the class. She soon realized she was mistaken.

Over the course of the semester, the professor, who Riley said still works at the University, made advances toward her, made her stay back after class under the pretext of discussing classwork, harassed her to come to his house and constantly messaged her over social media.

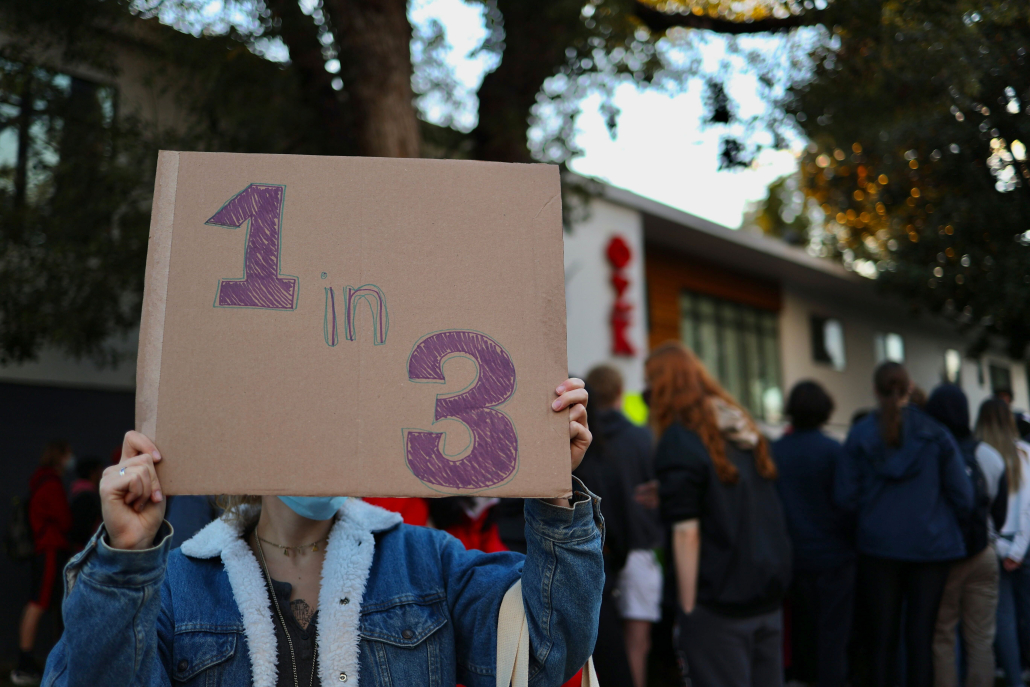

According to the Los Angeles Times, which cited a 2019 survey conducted by the Association of American Universities, one in four undergraduate females are sexually assaulted on campuses across the country. At USC, the statistics are almost one in three, 31% of female undergraduates responding they were sexually assaulted during their time at the University.

In the classroom

Following dinner with her professor at a “fancy” restaurant, Riley wanted to call an Uber back home, but the professor did not let her, insisting on driving her home even though he was drunk.

“He’s a very well-respected and well-known academic, so I believe that he uses that power to get what he wants and not get caught,” Riley said. “It worked on me because I started to know what was happening but didn’t fully realize it because of how much respect he has. And I thought I would just go along with it because I respected him too.”

Despite “forceful insistence,” Riley never went to his house or office, fearful of what the professor might do if she were alone with him. Still, he often made her stay after class and sat very close to her.

“I don’t know anyone else that has had this happen, but I feel very confident that it must have happened to other people just because of how quickly it happened to me,” Riley said. “It wasn’t a slow escalation. It was the first class that I ever had with this person.”

As Riley slowly started creating more distance from the professor, she said it began to reflect in her grades. After receiving a final grade lower than she expected, she emailed the professor and got a “nasty reply” where he said she wasn’t a good student — a stark departure from everything he had told her at the beginning of the semester.

Prominence in Greek Life

Beyond the classroom, incidents of sexual assaults are commonly reported within Greek life. On Oct. 20, the Department of Public Safety sent a communitywide email about multiple reports of drugging and sexual assault at the Sigma Nu Fraternity House. In the week following the initial email, DPS reported additional druggings and sexual assaults at Sigma Nu and other fraternities spanning from Nov. 10, 2018 to Fall 2021.

The USC community held multiple protests on the Row, outside Sigma Nu and in front of Bovard Auditorium following the initial DPS email and throughout the rest of the semester. Ashley, a sophomore, joined the protests as a survivor of sexual assault at a fraternity. She did not want to include the fraternity’s name included in the article.

During the virtual semester, Ashley, a sophomore living at an off-campus student housing complex near USC, would go to her neighbors’ small fraternity parties. At one of the parties, she felt more drunk than usual, even though she hadn’t had a lot to drink and ended up blacking out after an hour.

The next day, she found out from girls who were at the party that, when she tried to leave, the vice president of the fraternity, who had been following her around and bartending that night, took her to his room to give her a mask because she didn’t have one. She didn’t return for a while and had no recollection of the night.

“No one really asked questions because they all thought that I got the mask and left. I ended up finding out the next day from the president of the frat that I was [sexually assaulted] that night by the vice president,” Ashley said. “[The vice president] would text me over the summer as well, just kind of following up, making sure that I wouldn’t tell anyone.”

When Olivia, a 2020 graduate, found out about “everything going on” at USC, she decided not to return for homecoming out of fear of “running into certain people.”

As a gender and social justice minor, Olivia said she was aware of the resources offered by USC to survivors of sexual assault. However, it wasn’t until she had to use them after being sexually assaulted by a close friend in a fraternity that she realized the difficulty of navigating them after an assault.

After her drunk friend put his hand in her pants and touched her inappropriately when he thought she was asleep, Olivia “froze” and didn’t know what to do. She wanted to put as much distance between them as she could, but didn’t know if she would take any further action.

“I was really upset about it, and I was kind of second guessing myself. I didn’t think that I was going to report it or anything like that,” Olivia said. “What I kept saying to myself [was that] it could have been way worse. It could have been so much worse … But eventually I was like, ‘Wait, you literally have written papers on this and how no one reports anything. Why would you not report this? Because it’s still assault. You know, it’s still sexual assault. He didn’t have consent. So, that’s kind of what pushed me to finally go in.”

Following the incident, Olivia decided to fill out a Callisto form, which allows survivors to document details of their assault in case they decide to file a report in the future. Eventually, Olivia decided to go to Title IX after she saw her assaulter with one of her sorority sisters at her sorority’s invite.

“I think that if I was not a gender and social justice minor, with these very strong thoughts already, that I probably would not have reported it especially given — it’s bad to say — the low severity of it,” Olivia said. “At the same time, the low severity is what nudged me to report, because I was kind of like, ‘This is the whole point, right?’ Guys think they can get away with this stuff because it’s not ‘rape,’ and they think that that’s OK.”

For Chloe, a sophomore majoring in law, history and culture, being a survivor at USC felt isolating even before the incidents at Sigma Nu. When she worried about safety at fraternity parties, people told her she “just [had] to go to the right frat.” However, following the DPS email, many of her friends shared stories of being sexually assaulted at fraternities.

“Less severe forms of sexual assault, like groping, are so common at frat parties that people don’t even act like they’re assaults when they completely are, and it’s just been really heartbreaking,” Chloe said.

Even before learning about her friends’ stories of sexual assault, Chloe described feeling “dehumanized” at fraternity parties because the parties were “built so that all the frat boys can have all the access to women they could possibly want.”

“Just seeing my friends who weren’t survivors go through everything that I’ve gone through being a survivor for four years now — it just shatters my heart,” Chloe said. “My friends and all these women who used to move through life with joy just turned into shells of themselves … It’s just so incredibly unfair because rapists aren’t affected by rape. They don’t care, but it feels like a part of you has died for a little while.”

Consequences of reporting

According to the Association of American Universities survey, 84% of undergraduate and 87.4% of graduate students who experienced sexual harassment did not report the incident to any University resource. Riley had used Relationship and Sexual Violence Prevention Services — a University therapy service for gender and power-based harm — to help her heal from a “previous sexual trauma” unrelated to USC, but she didn’t trust USC resources to protect her in this case.

Riley said she confided in a woman professor in the same department, who reported the incident on her behalf to the department, the Office of Ombuds and Office of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion. However, no one reached out to Riley, and the professor did not recieve a response even after following up.

“[The lack of action] made me really not trust USC — that they care about my safety, that they care about student safety,” Riley said. “It was definitely a slap in the face and made me hate an institution that I had loved because I didn’t feel like it cared about me.”

Meanwhile, confiding in her professor affected Riley, who found herself “unable to attend class and do [her] homework for weeks.” Fear of USC’s inaction — based on other experiences she had heard about — and risk of the case consuming her life, prevented her from coming forward. Mixed with this fear was the guilt of not stopping the professor from behaving similarly with other students.

“I know that I could have gone to the Title IX office immediately and gotten an investigation, but I had a friend my freshman year of college where I was a witness to a Title IX case,” Riley said. “It was traumatic for me just as a witness to go through the Title IX process, of how much they questioned me and how much time it took out of my life … I felt like I wouldn’t be able to do school if I did a Title IX investigation against him.”

“[The lack of action] made me really not trust USC. It was definitely a slap in the face and made me hate an institution that I had loved because I didn’t feel like it cared about me.”

Riley, a 2020 USC graduate

Olivia echoed Riley’s sentiment and said she wouldn’t have been able to go through the reporting process during a normal semester. Her entire trial took place during a remote semester when, as a senior in her last semester, she was only taking two classes. That gave her the time to look over documents that were sent to her by Title IX, make notes and send back questions — all of which was a required part of the process.

“It’s probably extremely hard for someone to have to do while they have a normal set of USC classes, and I don’t think that there’s any support offered in that regard,” Olivia said.

Olivia said she found herself “pleasantly surprised” when the Title IX process ended with the University suspending her assaulter for a semester because she said “that doesn’t happen to a lot of people with Title IX.”

Holding fraternities accountable for members’ actions and making rapists fear consequences might be the only thing that helps, Chloe said. However, putting survivors through the “incredibly exhausting process” of reporting and going through a court process that can take months worries her.

“I don’t think that more sexual assault training will help,” Chloe said. “How is learning about consent going to stop someone who’s roofieing? How the hell can you actually believe that they don’t know exactly what they’re doing? They know exactly what they’re doing. You can’t roofie someone and think that it’s consensual, and what the hell is more training going to do about that?”

Next steps forward

Hannah initially thought the University was handling the reports of drugging and sexual assault at Sigma Nu well because of emails flooding her inbox and professors sharing University resources. However, after attending a party in November, the freshman found herself having difficulty finding help for a non-USC student who was assaulted within the Fryft zone and said USC needed to do more.

After having difficulty finding RSVP’s number, Hannah finally connected with someone, but she said she felt like the person on the line had never dealt with a sexual assault situation and did not know what to do. Since the event took place off-campus and the student didn’t go to USC, she said she was told the University couldn’t do anything and they would have to go to the police.

“The person who answered was very nice, and they were helpful, but you could tell that they didn’t really have any training or idea what to do,” Hannah said. “When I said the word assault, they were like ‘Oh, wow’ and … put me on hold for a very long time.”

For Olivia, the University’s unwillingness to adopt student suggestions and lack of progress has been especially frustrating. As part of a special topics gender studies class she took in Fall 2018, she and her classmates presented a list of actionable items that the University could implement to administrators to make students feel safer. The items included suggestions such as increasing the number of streetlights between the Row and campus, but Olivia said none of their ideas were implemented.

“I had a classmate who was on the USC Sexual Assault Task Force all four years, and they would always make recommendations and meet with administration,” Olivia said. “Nothing that they ever recommended ever came to fruition.”

USC announced a Working Group on Interfraternity Council Culture, Prevention, and Accountability in a communitywide email Nov. 11. that was supposed to make initial recommendations by Dec. 17, 2021. The group’s initial recommendations, including requiring security to be stationed at stairs and hallways leading to bedrooms, event planning oversight and mandated sexual assault and harrasment trainings for all members before resumption of social events, were announced in a campuswide email Jan. 18 by Provost Charles Zukoski.

Chloe said the creation of the committee felt like USC was waiting until things blew over and students were back home for winter break. Like other universities, she said she believes USC delays its response when students make demands until they get busy with school, finals or until leaders of the movement graduate.

“I really thought things had changed because we have a female president, and I thought what happened with George Tyndall couldn’t possibly happen again,” Chloe said. “I doubt that something of that caliber could, but I think I forgot that USC covered up what happened with Tyndall for decades. So, how can I really expect this school to stand with survivors when they wouldn’t even stand up for survivors when it was one of their own?”