Center for the Political Future discusses history, present of China

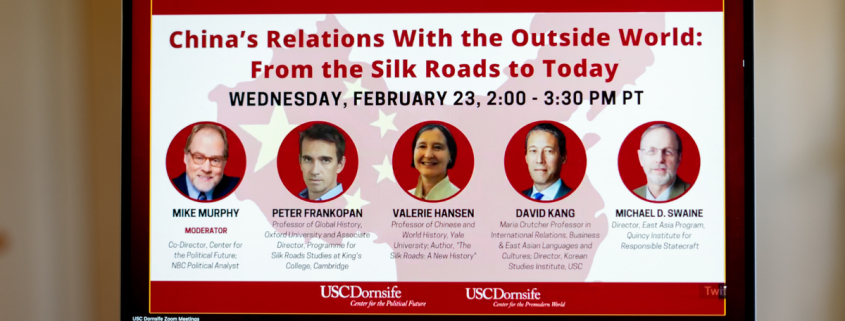

The Center for the Political Future hosted a virtual discussion Wednesday in partnership with the Center for the Premodern World to explore, starting with the Silk Roads, the history that led to today’s complex United States-China relationship.

Moderated by co-director of the Center for the Political Future Mike Murphy, the event featured speakers Oxford University professor of global history Peter Frankopan, Yale University professor of Chinese and world history Valerie Hansen, East Asian languages and cultures professor David C. Kang, and East Asia Program at Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft director Michael D. Swaine.

After brief introductions, Murphy invited Hansen to share some background on the Silk Road’s impact on China’s outlook and relations with European and other nations.

According to Hansen, use of the Silk Road started in the second century B.C. and continued through until 1000 or 1500 A.D. The routes were significant channels of foreign influence on China, although Hansen noted the complexity in China’s contact with other countries.

“In the beginning, the Chinese didn’t have a view of the outside,” Hansen said. “In the beginning, China was not a unified block. It’s a bunch of different regional kingdoms, and they have contact with each other and then they also have contact with powers to the West.”

Swaine also cautioned against generalization and elaborated on China’s history, a train of various dynasties and federations with different views on issues such as security. These federations experienced friction and conflict with their neighbors, as well as periods of relative peace and calm. Relationships were often built on mutually beneficial trade rather than military aggression, with some exceptions. The past 150 years have been most important in shaping the China of today, Swaine said.

“Interactions with its periphery and with countries further afield on the basis of very unequal relations, a large part of that was Western imperialism; the kind of division that that created within the country, especially when the country was weak,” Swaine said. “You’ve had a history of this kind of experience that I think really has a very strong influence on China today.”

Frankopan presented an alternative to the common conceptualization of the Silk Roads as a link between China and Europe, preferring to envision them as a “big web” of links between various small communities. He also said that interactions such as knowledge transfer between some of these communities started long before the second century B.C. Frankopan explained China’s attempts to connect with the past and bring it to the present.

“You could characterize China under President Xi as making China great again,” Frankopan said. “This is kind of the signature move of the 21st century, which is: ‘This is what China once was, this is how it connected to the outside world, we’re going to resurrect and reheat these kinds of networks.”’

Moving into the modern era, the speakers discussed — in contrast to the Western narrative — the Chinese perspective on their increasing power and economic growth. Hansen presented the “spin answer” of China retaking its “rightful place in the world,” a message found in many of President Xi’s speeches.

“So the question is, ‘What is he thinking about?’” Hansen said. “Is there a historical moment that he’s thinking about?”

According to Hansen, historically, due to the size of its population in a time when size equated to power, China was often the biggest, most powerful country.

Swaine agreed that this was a common message from the president, but said that the president does not completely represent Chinese attitudes.

“I do think it’s important to not simply boil whatever China’s thinking and intending down to what Xi Jinping thinks,” Swaine said. “He’s a particular type of leader who’s playing on Chinese nationalists and other feelings to maintain order and stability in a very rapidly moving society …. and to serve the status and prestige feelings of the Chinese population.”

The speakers then offered their thoughts on what is overlooked in the U.S.’s response to China’s rise. Kang highlighted East Asia’s hegemony compared to Europe and the history of relations in the region. Smaller surrounding nations such as Korea and Vietnam have historical experience interacting with a large, powerful China that prepared them for China’s recent rise.

“One reason you are seeing a muted response from all the countries in the region to China’s rise is this is totally expected,” Kang said. “They know they have to live with a big China. That’s not a question … Now, the present day is totally different from the past. So yes, it’s a modern system … but they’ve done it before and that’s what they’re trying to do today.”

Swaine added that such countries rely on China for growth, a strong incentive to maintain friendly relations. He believed that China expects a certain degree of acquiescence from these countries but has not articulated a clear vision for the region.

“Does China think that it needs to in some meaningful way dominate the region?” Swaine said. “Or is China willing to live with a region where it doesn’t have that kind of dominant power, but it certainly is respected in a variety of ways, but then it can engage with other nations in the region on a common basis, on a common foundation more or less, and can this be done without the United States controlling the situation, if you will, influencing how Asian countries interact?”

The speakers then shared the ways they hope people will better understand China.

Hansen clarified that, historically, China had never been isolated from the outside world to the extent that people often believe. Frankopan and Kang both underscored the limited nature of people’s understanding of China.

Kang emphasized the importance of developing an understanding of Eastern history comparable to that of European histories. Promoting this historical awareness and considering the lessons of Eastern history more seriously, he said, is key to discerning how people view themselves and their relations to each other.

“Intuitively, shouldn’t regions of the world with different philosophies, different religions, different languages, social structures — why wouldn’t the politics be different as well?” Kang said. “I think a centering of East Asian history would be a great step in the right direction.”