For undocumented youth, DACA is a lifeline

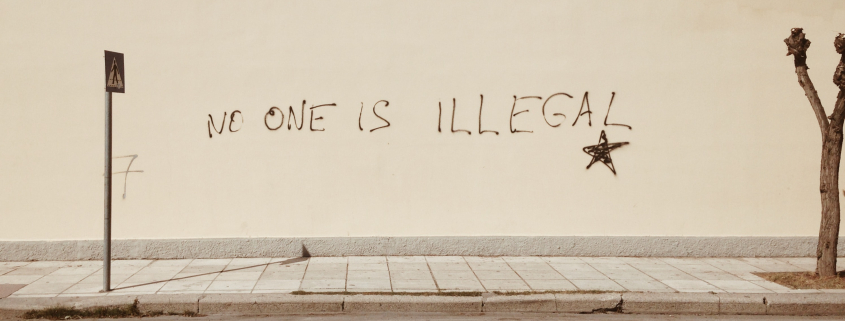

“Just come here legally.” Many immigrants hear this phrase far too often. The use of the term “illegal” in the subject of immigration tends to connect immigration to legality, with a specific focus on racialization and migration. What this phrase insinuates is that immigration is a simple process that anyone can do, but when you’re trapped in war zones with little to no resources, it feels more like a Sisyphean task.

As Haitians flee from humanitarian crises and citizens of Latin American countries take on the journey north, the border and all the political baggage it carries only reminds them of the hatred the United States carries for people like them. The media often refers to migration as a wave and amplifies calls for a focus on border enforcement and a wall to build. The conception evoked is that immigration is an invasion, which is far from the truth.

Through the immigration journey, parents carry their children with them. Many would move mountains for their children to have a better life; more exactly, they would cross mountains to move to an entirely new country. These children, sometimes mere infants, are often unaware of where they are moving; unaware that they may grow up to a life filled with the question of “where are you from?”, unaware of the lack of protection, unwarranted hostility and unjust treatment within they may face in education, work and the legal system.

Sadly, a common response to the struggles of many undocumented immigrants is to “just come legally.” Indeed, the statement serves as proof that those who say it possess little knowledge of the U.S.’s citizenship process. It can take up to ten years to obtain a green card, years which are not guaranteed as many continue to struggle to survive in their host countries.

As an undocumented person, I have always felt as though I had to hide in the shadows of the U.S., due to a lack of support. As children arrive in the U.S., we do not hold citizenship nor the benefits granted to citizens. However, we were raised in the U.S. and, being in the country, we have an excellent knowledge of it — the history, culture and language — only to not be recognized as Americans no matter how hard we try.

In 2012, there was a spark of hope as the Department of Homeland Security announced Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals. This executive order authorized immigrant children and people aged 16-30 federal protection, work permits and a temporary social security number. However, this order did not grant a direct pathway to citizenship.

Even the order’s announcement has sparked conversation: is DACA constitutional? Former President Donald Trump announced in 2017 his plans to end the DACA program, causing fear in applicants and those who were currently in the program. “Congress, get ready to do your job — DACA!” read his tweet.

On June 18, 2020, the Trump administration moved to terminate the DACA program, a decision that overruled by the Supreme Court; the Justices ruled 5-4 in favor of DREAMers. The ruling allowed U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services to accept DACA applicants for both previous and new recipients, as the pause in applications due to the Trump administration’s attempts to permanently end the program affected the status of many in the country.

On Oct. 5, 2022, the Fifth Circuit Court declared the DACA program unconstitutional. Judge Andrew Hanen from the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Texas claimed in his 2021 ruling that “Texas [sought] to protect its legal residents’ economic and commercial interests from labor market distortion caused by DACA.”

The truth? A PBS news brief by Courtney Vinopal looked into figures from the New American Economy that show that DACA recipients paid $4 billion in taxes to the U.S. government in 2017. The Director of Quantitative Research at the New American Economy Andrew Lim went on to state that “the vast majority of [the DACA-eligible individuals] — 93% — are working, if they’re not in school. Together, every year, they earn more than $23.4 billion.” Billions would be lost if DACA were to end, and the labor market could implode all together.

A nine-digit security measure holds us back, and we are tired. We are tired of proving that we are humans. Yet, it feels as though how we got into the country is the only thing many focus on. Our only chance? Applying for citizenship through a long, tedious process, only to be tested on six U.S. history questions that determine whether or not we truly “belong” in this country.

As of 2023, current DACA recipients and youth migrants are unsure of whether DACA will remain. Universities, colleges and high schools need to be aware that undocumented students need support from teachers and the reassurance that no dream shall remain a dream, but become a reality.

Immigrants are people. We are not aliens or “illegal”. We are those who do not have the great privilege of being born with wealth and safety, something completely out of our control. Undocumented students have ambition. We work twice as much just for institutions to deny us support. We are tired of sharing the good we have contributed to this country just to convince people we are human. We want recognition; why does this country fail to hear us?