Lessons Learned: Grief, tangerines and the Moon — lessons on mortality

Content warning: This piece contains references to death.

Look at the Moon. It’s the same Moon whether you look at it from here in Los Angeles or anywhere else in the world, we share the same Moon. Isn’t that neat? When I was six, I remember walking home late at night from my cousin’s house. The night was cold, and soft moonlight peeked through the clouds, shedding light onto the sidewalk, as if illuminating my way home. Trying to grab the elusive ball of light within my child-sized hands, I ran after it, with my light-up Skechers keeping away the dark. But it was too far away. In an attempt to be a little closer to the Moon, I asked my dad for a shoulder ride. And so we walked home, one 7,533 miles from our humble hamlet in Viet Nam.

Tết Nguyên Đán, better known as Tết or Lunar New Year, is celebrated on the first new moon of the lunisolar calendar. Other variations of it are celebrated in China (Chūnjié), Korea (Seollal) and other countries within the Sinosphere. “Xuân đã về, xuân đã về (spring is coming)”, and “Tết Tết Tết Tết đến rồi (Tết has come).” Vietnamese communities around the world know the lines to these songs all too well. Spring is here, and it’s time to celebrate — right?

I remember my first year spending Tết away from home: Feb. 1, 2022. I had recently received news that the boy I was dating at the time was killed in a tragic car accident. And so at 2:34 p.m., I got out of bed, washed my face and sat at the dining table of my apartment, forcing down what was my first (and probably my last) meal of the day. It was Tết and there I am, all alone, eating Cuties mandarin oranges, one after the other. Mandarins are eaten during Tết as a symbol of wealth and good luck. And, God, could I use some good luck. Ttch. Blood began to pool up under my thumb as the mandarin peel slipped under my fingernail, splitting skin and nail.

Just what I needed.

After cursing the heavens, I continued to peel mandarin after mandarin into spirals, stars and ugly piles of peel that broke off a bit too soon. I’m not superstitious. I’ve never been. But grief had me looking for luck in the strangest of places. It’s funny how we do that.

Anyone who celebrates the New Year understands how hectic things get as it approaches. I’d wake up to the sound of my sister’s nagging, my parents bickering. It’s almost Tết — that means we have to clean EVERYTHING. And so I would vacuum the house. My mom, sweeping. Sister, throwing out hoarded objects. And my dad, smoking a Marlboro cigarette with his morning cup of cà phê đen đá (Vietnamese black coffee). No wonder my parents were fighting. We don’t clean during the first four days of Tết; we wouldn’t want to sweep away all the good luck.

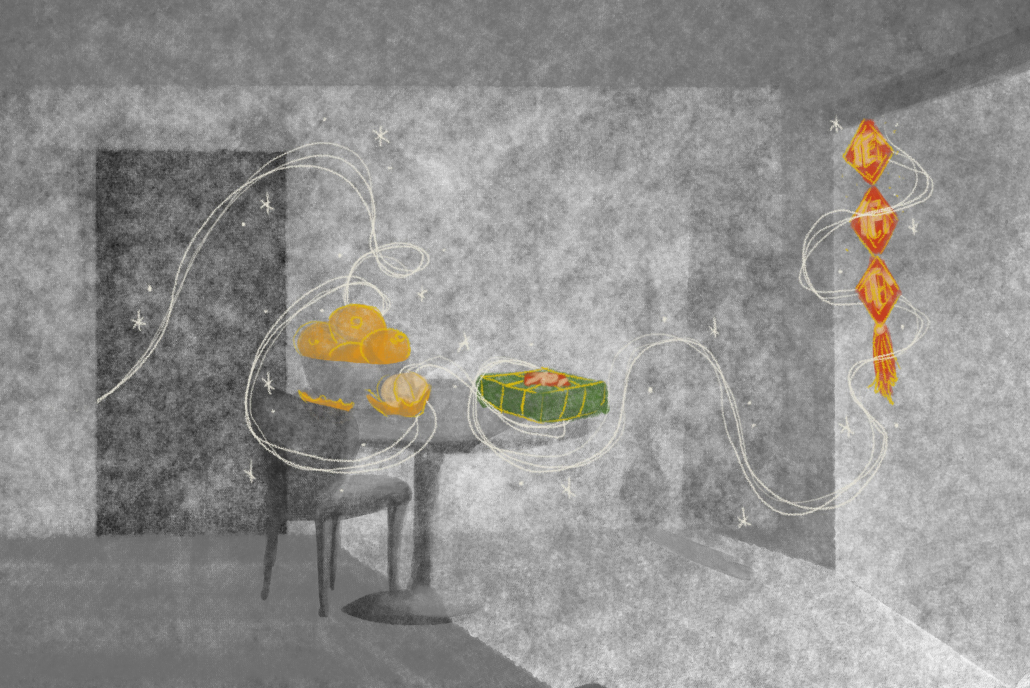

After all the cleaning, we’d sit as a family, huddled around baskets of banana leaves and glutinous rice soaked in water making bánh tét, a Central/South Vietnamese rice cake made of glutinous rice, mung beans and pork belly. It’s a traditional dish eaten for — wait for it — good luck. See the pattern? It was back-breaking work. But it was one of the few things that got us together as a family. So we’d scoop generous heapings of rice onto banana leaves, add the filling and roll them up and tie them into a neat little package, each person doing their part in the multi-step process.

And on the day before Tết, we’d get into our áo dài and go to the temple to offer food, thanks and prayers to whatever larger being was out there. We’d watch múa lân parades, as lion dancers (they’re actually Vietnamese unicorns) and Ông Địa, the Earth God, prance up and down the streets. We’d play bầu cua cá cọp (lit. ‘gourd crab fish tiger’), a Vietnamese gambling game and Tiến lên, the Vietnamese card game also known as ”Thirteen.” We’d enjoy the fruits of our labor. We’d exchange lì xì (lucky money) in little red envelopes and eat the food we’d prepared the days before. And as the clock strikes midnight, we’d end the day by lighting firecrackers to ward off evil spirits.

On my first Tết away from home I sat homesick, missing the bickering of my family. I would miss the stupid arguments they’d have after drinking too much, after losing too much money gambling. I miss the smell of gunpowder that filled the air. The red casings of firecrackers littering the streets. That year, I forgot to clean. Forgot to ward off evil spirits and give up offerings. And so, I sat there all alone, peeling mandarin after mandarin and lighting a single stick of incense, offering a silent prayer to the boy I love. Because in that moment, I could use all the luck I could get.

Man Truong is a junior writing on reflections made in life. In a world full of different personal beliefs and philosophies, he makes sense of it in his column, “Lessons Learned.”