Order in the Court: Native community talks potential overturn of Indian Child Welfare Act

This is the first article in an ongoing series investigating Supreme Court cases slated for the current term and their impacts on the USC community. In light of current events, the Daily Trojan News section believes it to be in the community’s interest to include the goings-on of the Court in our coverage. New installments will be published weekly.

Early in her life, Eleanor Moore’s paternal great-great-grandmother was adopted away from her tribe in western Washington State. (Moore said she does not know which.) After generations of assimilation into American culture, Moore said, she struggled to reconnect with her Native heritage.

“We haven’t really been tribally affiliated,” said Moore, a freshman majoring in sociology and a member of the Native American Student Association. “I joined NASA when I got here because I wanted to be in a community … and be in a space that my dad, for example, didn’t get the chance to be a part of. [I’m] just trying to connect with the far-off parts of me that I never really learned about.”

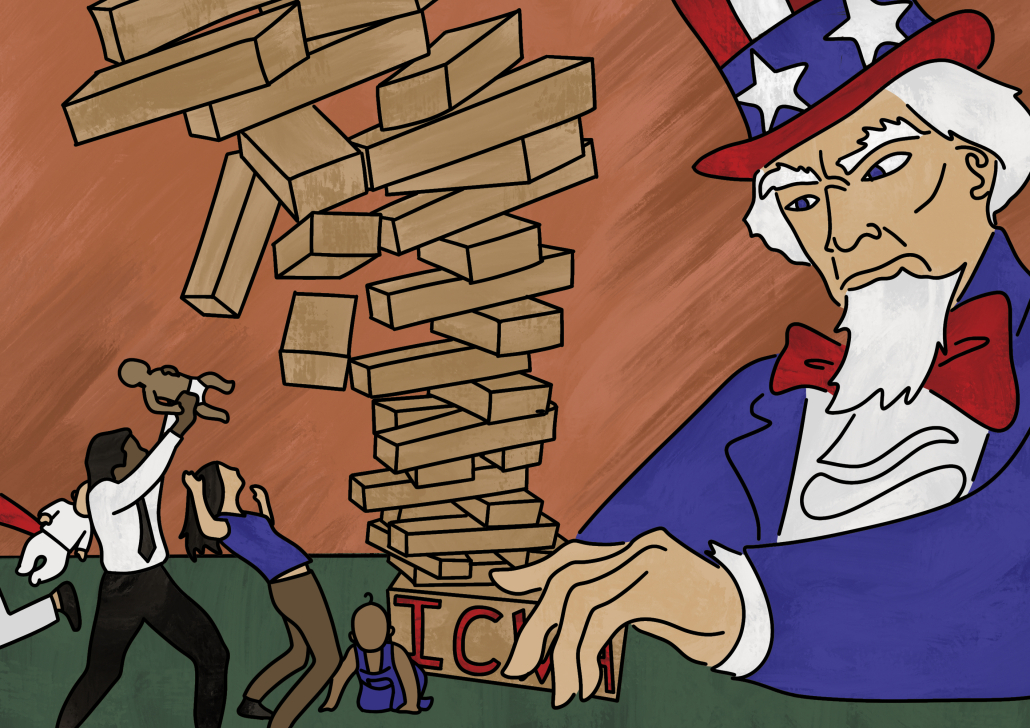

In 1978, Congress instituted the Indian Child Welfare Act to end the separation of Native American children from their families, primarily by returning the jurisdiction of Native children who are adopted or sent into foster care back to the Native tribes. The implementation of the act sought to eliminate instances of cultural erasure and offer Native children the opportunity to live in Indigenous tribes.

Now, ICWA faces a potential repeal with Haaland v. Brackeen, a pending Supreme Court case argued Nov. 9. The Daily Trojan spoke with Indigenous community members at USC, who say Native families would struggle to preserve aspects of their culture and sovereignty if ICWA is overturned.

Haaland v. Brackeen dates back to a 2018 complaint filed in a Texas district court, by seven non-Native individuals — backed by the states of Indiana, Louisiana and Texas — alleging that the ICWA had hindered their attempt to adopt Native children. Plaintiffs argued this constituted discrimination on the basis of race, as the act prioritizes returning Native children in adoption or foster care programs to their extended family or the Native people of their tribe.

Meanwhile, the United States government — alongside the Cherokee Nation, the Oneida Nation, the Quinault Indian Nation, the Morongo Band of Mission Indians and the Navajo Nation as co-defendants — maintains that Congress has the right to regulate the tribes under ICWA, as it is a valid exercise of Congress’s plenary power over Indigenous affairs.

A majority of tribes are in favor of sustaining ICWA. Out of the 574 tribes formally recognized by the U.S. government, 497 Tribal Nations and 62 Native organizations have signed the 21 briefs submitted to SCOTUS in favor of upholding ICWA.

Jair Peltier, the graduate cultural ambassador for the Native American and Pasifika Student Lounge and a fourth-year Ph.D. student studying Indigenous sovereignty, said that the act played a vital role in keeping Native children in Native families and preventing them from being enrolled in boarding schools or put in adoptive or foster care systems. These systems were used in order to enforce Native assimilation, Peltier said, and ICWA was able to address that issue.

“The vast majority of children who ended up in the care of these [adoptive] parents … had their identity stolen,” Peltier said. “They were not given the option to choose to live a traditional kind of Indigenous lifestyle or to be assimilated into the broader American society.”

Tok Thompson, a professor of anthropology at the Dornsife College of Arts, Letters and Sciences who teaches a course on Native North Americans, said that the plaintiffs’ argument does not hold, because “this has nothing to do with race … what this covers is Native Americans as a legal entity, as a sovereign group.”

“In the U.S. Constitution, it enumerates the different rights of the Congress, and one of them is that the Congress shall have the right to make treaties with … the various foreign Indian tribes,” Thompson said. “[This puts] Indian tribes on the same level of treaty making as foreign nations and foreign nation-states.”

Even though it’s only seemingly applying to this one particular case of children being adopted into non-Native families, the potential to affect other aspects of tribal sovereignty is there … So it’s not just a question about adoption. It really is the question about: Do tribes have a separate political identity? Do they have sovereignty?

Jair Peltier, graduate cultural ambassador for the Native American and Pasifika Student Lounge and a fourth-year Ph.D. student studying Indigenous sovereignty

Raegan Kirby, a recent Native graduate who was on the executive board for NASA, said she agreed with these sentiments after learning more about the classification of race through a modern-day lens.

“There is a phenotype of what a Native ‘should’ look like,” Kirby said. “But it’s not really a reality, especially because there are so few of us. I think that Native Americans are a very, very diverse group of people … Just thinking about being Native American as a race honestly doesn’t make sense.”

Students and faculty alike say that the implications of reversing ICWA could be dire.

“[Overturning ICWA] is counterintuitive,” Moore said. “Unfortunately, while there have been steps to right some of the wrongs, they don’t do a very good job of it. It’s hard to watch because it was so good to have, but the idea of it being taken away is really harmful. I don’t think people that are arguing against it don’t realize it. There’s a part of it that they’re not seeing.”

Peltier said that not only could overturning the act result in a loss of cultural ties for Native children being adopted by non-Native parents, but the case could also entail a wider scope of issues at stake.

“Even though it’s only seemingly applying to this one particular case of children being adopted into non-Native families, the potential to affect other aspects of tribal sovereignty is there,” Peltier said. “So it’s not just a question about adoption. It really is the question about: Do tribes have a separate political identity? Do they have sovereignty?”

According to Kirby, Indigenous people consider tribal sovereignty as important for Native states, as this is what allows them to govern themselves on the land they originally occupied. Peltier said he was concerned that Haaland v. Brackeen — by posing a threat to tribal sovereignty — also threatens Indigenous communities at large.

“Once you undo tribal sovereignty, let’s take it a step further,” Peltier said. “What happens to Indian Health Services? What happens to the Bureau of Indian Education? What happens to the Bureau of Land Management? All of these federal systems and structures that have been created to address … the reality of the federal trust relationship start to potentially unwind as well.”

Kirby said that tribal sovereignty is particularly important when considering the longstanding history of cultural genocide of Indigenous people by the U.S. Overturning the act, she said, would be discouraging to the survivors and victims of generational trauma.

“ICWA, at the end of the day, is about much more than just Native children that are going through the adoption process or the foster care system,” Kirby said. “A potential overturning of ICWA … could also overturn lots of other precedents that have to do with tribal sovereignty.”