Food insecurity spiked in low-income LA County households in 2022, USC study shows

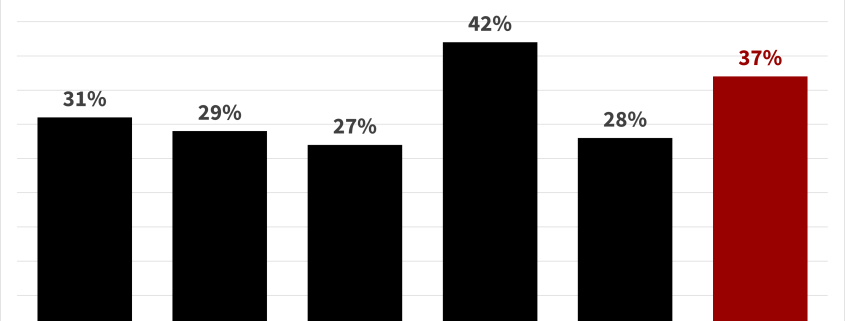

More than one-third of the low-income households in Los Angeles County experienced food insecurity in 2022 – an increase from the pre-pandemic level of 27%, research from the Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences’ Public Exchange found.

Published in February, the study analyzed data from the Understanding America Study, a USC internet survey panel and 31 interviews conducted with L.A. County residents who self-identified as experiencing food insecurity.

The food insecurity rate among low-income residents had been improving prior to the pandemic, with a 4% drop from 2011 to 2018. During the peak of the pandemic, the food insecurity rate surged to 42% but quickly returned to 28% in 2021.

The tide turned in 2022, when the all-household food insecurity rates in L.A. County rate spiked to 24%.

“The first year of [coronavirus], 34% were food insecure. It got a lot better — down to 17% in 2021. And now in 2022, we’re going in the wrong direction,” said Dr. Kayla de la Haye, project lead of the study.

De la Haye, associate professor of population and public health sciences, warned that the return of food insecurity rates to pre-pandemic levels would disproportionately worsen healthy food access for individuals who are low-income, women, young adults, Latine and Black.

The data sheds light on food inequality in L.A. County — food insecurity rates among Black and Hispanic residents are three times higher than the rates among white residents in 2022.

“We also see that certain segments of the community are way more impacted by [food insecurity] than other people,” de la Haye said. “Part of this is really an issue of food justice and unequal financial access in somebody’s neighborhood to affordable healthy food.”

Other factors include inflation, which causes food prices to skyrocket, and the ending of the pandemic-era programs such as CalFresh emergency allotments and Pandemic-EBT.

“The taking back of their benefits just makes their life became harder,” said Mengya Xu, a project researcher and graduate student studying population, health and place. “We also think about what we can do to help them to gain more that benefits to balance their budgets that can be used for food.”

As part of the three-year research project, the study dives into four predominantly Latine neighborhoods — Boyle Heights, City Terrace, El Sereno and Lincoln Heights — where half of the census is characterized as “food deserts” by the United States Department of Agriculture, to analyze food availability and resident’s lived experience.

There are 269 retail outlets that sell groceries, inducing stories like gas stations whose primary business is not grocery sales, in the four neighborhoods, according to on-the-ground audits conducted by USC researchers. But de la Haye said a large number of retail outlets shows the food desert label doesn’t accurately represent the communities.

“A lot of folks could reach one of those stores within a 15-minute walk of their house,” de la Haye said. “But one of the challenges is that a lot of the stores that were there just didn’t have a good variety of healthy and affordable food.”

Almost half of the retail stores provide less than 25% of space for groceries, and a majority of them sell processed food, while whole foods such as fruit, vegetables and grains are less accessible, the study found.

Smaller businesses that sell food products such as bakery stores and dollar stores account for 87% of the retail outlets — the remaining 13% being large supermarkets where fresh vegetables, fruit and milk are more abundant and affordable. Residents shared in interviews about their demand for more food options, higher quality and more affordable food in local stores.

“Most residents would like to see the existing stores in their neighborhood provide better access to healthy high quality, organic, affordable foods,” said Cynthia Ramirez, a research assistant in charge of conducting and analyzing qualitative interviews.

In August 2022, USC researchers interviewed 31 residents in the four neighborhoods, gathering information on residents’ sources of food, challenges and improvements in access to healthy food. Although it seems like a small number, the sample of interviews is adequate enough to reflect residents’ main concerns.

Ramirez, a Ph.D. candidate in the department of Population and Public Health Sciences, said that data saturation occurs when the marginal data doesn’t provide any new information. In the food insecurity research, data saturation happens between the twelfth and twentieth interviews.

“Because we weren’t conducting interviews across several different neighborhoods, we decided to keep collecting data, just to make sure that we didn’t miss any key insight,” Ramirez said.

The study combined databases from the Los Angeles Regional Food Bank and Findhelp, a social services search engine, to investigate the 30 food assistance programs operating in the four neighborhoods. Almost one in four of the households don’t have access to any food assistance provider within a 15-minute walk, the study found.

“It’s not about just getting individuals to have the cash they need every month [though] that’s part of the solution,” de la Haye said. “The whole system really needs to be improved so that there’s equal access to healthy food for everyone.”