We’re not just girls; we’re so much more

The “just a girl” trend is antithetical to feminism: We must respect ourselves.

The “just a girl” trend is antithetical to feminism: We must respect ourselves.

For the past few months I have used the phrase “I’m just a girl” or “you’re just a girl” with my friends — probably a little too often — to jokingly excuse some action of mine or theirs. While doing so, I, like many other women and girls who have also adopted the “just a girl” trend, unknowingly became a culprit of infringing on feminism.

Popular examples of the trend demonstrate the joke’s damaging consequences. For instance, on TikTok, user @yolundahura posted a video showcasing her car stuck in her garage entrance, along with the text “I’m just a girl.” TikTok influencer @chrissychlapecka has similarly participated in the trend by posting a video reassuring viewers that “baby you’re not a failure, you’re literally just a girl.”

The trend has also appeared on other social media platforms, such as Instagram, with similar sentiments. It would be easy to mistakenly characterize the trend as unproblematic. On its face, it seems to represent women embracing their imperfections, like causing a car mishap, and supporting other women through failures, as @chrissychlapecka’s video appears to exemplify.

However, beneath this seemingly accepting, supportive and positive exterior lies a darker truth: These statements could be perpetuating misogynistic ways of thinking.

Although the statements are accepting of our failures, by connecting those failures specifically to being just a girl, they imply our flaws are directly the results of being a girl or woman. This supports notions that there are skills which girls and women are intrinsically incapable of and that we should be held to lower standards than everyone else.

These ideas have extended even into online discussions of careers and academics.

One user on TikTok, @houseofmaeli, made a video where a vice president of marketing asks, “What are your thoughts on that?” cutting to her as a mouse with a pink bow in her hair responding with “I’m literally just a girl.”

Additionally, a TikTok video by user @sojaaa022 features her making the pattern of a bow on her graphic calculator with with the caption, “i dont know how to do math. im just a girl.”

Both of these examples of the “just a girl” phenomenon seemingly support that women aren’t able — and consequently shouldn’t be expected — to succeed at activities that involve utilizing intelligent thought, such as discourses on marketing or doing math, and instead should just be left to being cute with their bows.

When critically examining such rhetoric, we must take into account internalized sexism. According to Steve Bearman, Neill Korobov and Avril Thorne’s research in the Journal of Integrated Social Sciences, internalized sexism occurs when “women enact learned sexist behaviors upon themselves and other women” and is exemplified when women devalue their capabilities.

The implications of the “just a girl” phenomenon — that women are fundamentally incapable of certain intellectual activities — serve as instances of women devaluing their capabilities and demonstrate internalized sexism.

Such alignments reinforce sexist notions that women aren’t smart or don’t belong in the workforce — stigmas that previous waves of feminism fought to eradicate.

This is particularly relevant to second-wave feminism, which was motivated by French feminist theorist and writer Simone de Beauvoir’s idea that “social constructs of gender lead to the view that women are inferior,” according to Human Rights Careers, and that sought to challenge such stereotypes of women’s inferiority.

Moreover, the Gender Action Portal from the Harvard Kennedy School highlights, “Women’s belief that their value is determined by their beauty … negatively impacts women and gender equality.”

Accordingly, by often replacing intellectual activities with activities centering around cuteness or beauty, the “just a girl” phenomenon further counteracts feminism.

So, instead of continuing to degrade our value as women and setting back feminist progress by excusing our failures with claims that we’re just girls, we should remember the immense value of our womanhood.

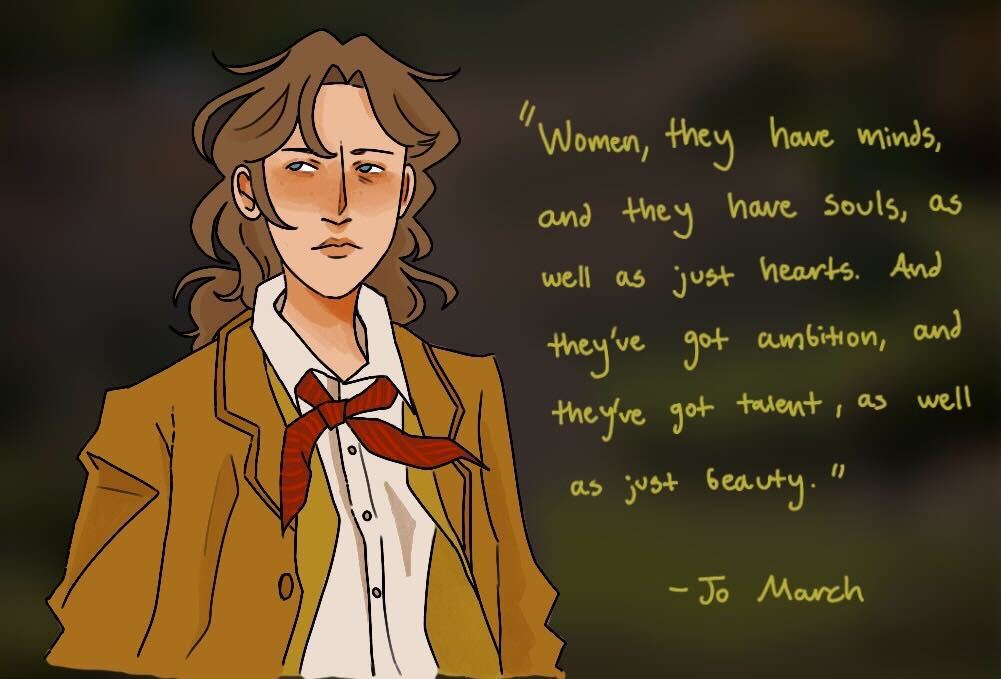

As Jo March (Saoirse Ronan) said in “Little Women” (2019), “Women, they have minds, and they have souls, as well as just hearts. And they’ve got ambition, and they’ve got talent, as well as just beauty.”

To treat ourselves with due respect, we should replace the just a girl excuse with “just a human” or “person.” In doing so, we’ll be able to maintain the positive intentions of the trend of accepting our flaws as people and supporting each other, without supporting harmful and sexist stereotypes about women’s capabilities.

We are the only independent newspaper here at USC, run at every level by students. That means we aren’t tied down by any other interests but those of readers like you: the students, faculty, staff and South Central residents that together make up the USC community.

Independence is a double-edged sword: We have a unique lens into the University’s actions and policies, and can hold powerful figures accountable when others cannot. But that also means our budget is severely limited. We’re already spread thin as we compensate the writers, photographers, artists, designers and editors whose incredible work you see in our daily paper; as we work to revamp and expand our digital presence, we now have additional staff making podcasts, videos, webpages, our first ever magazine and social media content, who are at risk of being unable to receive the support they deserve.

We are therefore indebted to readers like you, who, by supporting us, help keep our paper daily (we are the only remaining college paper on the West Coast that prints every single weekday), independent, free and widely accessible.

Please consider supporting us. Even $1 goes a long way in supporting our work; if you are able, you can also support us with monthly, or even annual, donations. Thank you.

This site uses cookies. By continuing to browse the site, you are agreeing to our use of cookies.

Accept settingsDo Not AcceptWe may request cookies to be set on your device. We use cookies to let us know when you visit our websites, how you interact with us, to enrich your user experience, and to customize your relationship with our website.

Click on the different category headings to find out more. You can also change some of your preferences. Note that blocking some types of cookies may impact your experience on our websites and the services we are able to offer.

These cookies are strictly necessary to provide you with services available through our website and to use some of its features.

Because these cookies are strictly necessary to deliver the website, refusing them will have impact how our site functions. You always can block or delete cookies by changing your browser settings and force blocking all cookies on this website. But this will always prompt you to accept/refuse cookies when revisiting our site.

We fully respect if you want to refuse cookies but to avoid asking you again and again kindly allow us to store a cookie for that. You are free to opt out any time or opt in for other cookies to get a better experience. If you refuse cookies we will remove all set cookies in our domain.

We provide you with a list of stored cookies on your computer in our domain so you can check what we stored. Due to security reasons we are not able to show or modify cookies from other domains. You can check these in your browser security settings.

These cookies collect information that is used either in aggregate form to help us understand how our website is being used or how effective our marketing campaigns are, or to help us customize our website and application for you in order to enhance your experience.

If you do not want that we track your visit to our site you can disable tracking in your browser here:

We also use different external services like Google Webfonts, Google Maps, and external Video providers. Since these providers may collect personal data like your IP address we allow you to block them here. Please be aware that this might heavily reduce the functionality and appearance of our site. Changes will take effect once you reload the page.

Google Webfont Settings:

Google Map Settings:

Google reCaptcha Settings:

Vimeo and Youtube video embeds:

The following cookies are also needed - You can choose if you want to allow them: