Voyeurism, narcissism and vanity thrive in ‘Public’

Before you could tag yourself in Facebook pictures, organize your Top 8 friends on MySpace or send @MileyCyrus a love tweet, there was a web pioneer in the ’80s and ’90s named Josh Harris, whose aggressive business tactics and eccentricities have been captured by director Ondi Timoner in the searing documentary We Live in Public.

Winner of the Grand Jury Prize at the Sundance Film Festival, We Live in Public explores the privacy and mental strength we surrender in order to achieve fame and recognition through the easiest and fastest-growing form of communication — the Internet. Though darkly unsettling and at times infuriating, Timoner’s documentary is an honest and relevant account of a dot-com miscreant fueled and funded by the birth of the Internet age.

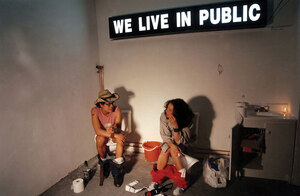

Candid camera · The documentary We Live in Public, which won the Grand Jury Prize at the 2009 Sundance Film Festival, follows Josh Harris, an early web innovator who experimented with Internet privacy. - Photo courtesy of Acme PR

The film charts Harris’s career through the ups and downs of working with a new and exciting invention and what it does to his sanity. He was quick to move in on the dot-com bubble when it exploded in the early ’90s, starting with Jupiter, a web-based business that quickly created the multimedia website pseudo.com that was, as Harris describes, intended to “put CBS out of business.” The million dollar-grossing website allowed users to comment on live webcam feeds, giving the camera subject a low-dose helping of narcissistic validation.

Timoner smartly chooses to focus on Harris, though, and what the unexpected success of his entrepreneurship does to his personal life and how it turns him into just as much of an egomaniac as the users of his creation.

Harris then begins to construct an underground empire in New York City; he throws wild parties for computer nerds and creates a face-painted alter-ego named “Luvvy,” who he embodies to counteract his high-stress, high-profile title as an Internet businessman. This is just the first in what would be many blips in his sanity. He begins to spend his money on vanity “experiments” — the most drastic and fascinating of which was a Big Brother-type project he called “Quiet: We Live in Public,” which had more than 100 New York City artists living together in cubicles while webcams videotaped their moves every second of the day. Culled from more than 1,000 hours of footage, the final project shows people running around naked, showering together, having sex in their cubicles and fighting over food. By harnessing the Internet’s ability to feed our need for recognition, Harris plays the role of God — or as the subjects call him, “Oz.” Over time, it becomes harder to classify him as one particular person. He is a computer geek, an entrepreneurial whiz kid, a performance artist, a face-painted alter-ego, a party boy and, now, the creator of his own universe.

After the NYPD busts Harris, assuming his project was a post-apocalyptic survival bunker for a cult of Y2K conspiracy theorists, he decides to take his hunger for fame to the next level by becoming the first man to completely document his life with his girlfriend on video. He places cameras all over his apartment — including his cat’s litter box and inside his toilet — and, like a real-life Truman Show, set up a website broadcasting his life every minute of the day.

Using Harris’ personal experiment as his prime example, Timoner focuses on the stark contrasts between living on and off camera, which Harris’ girlfriend explains lies in how the cameras skews motivations and actions. Eventually, the constant attention from voyeuristic web users destroyed the couple’s relationship and Harris’ career. With the stock market declining and his website losing hits because the loss of his girlfriend, Harris eventually found himself up to his neck in debt and decided to stop living in public for good.

By the end of the film, Timoner leaves us with an ambiguous message and it is difficult to tell if the rise and fall of Harris was due to his own lack of responsibility or the instability of predicting the next best dot-com sensation. Either way, Harris ends up as a basketball coach in Ethiopia — a land that is “rich with culture, not money” — as the greatest victim of the electronic, privacy-stealing empire he built. Though a different person, he is not necessarily sad but seems wounded by what he could have been in the wake of the successful social networking websites that started popping up at the turn of the century.

The film itself adds another layer to Harris’s story — putting audience members as voyeurs of a tainted exhibitionist — ultimately asking us if the value we see in the film is due to our own fascination of watching someone’s life crumble on screen or our ability to identify with Harris’s extreme vanity. Although We Live in Public is a bleak look at the fast-paced boom of the information age, it also profiles a man who tries to stay one step ahead at all times. This tactic is a lot like the Internet itself — rich with money, but lacking insight.