Perks of higher education are worth the price tag

As the price of higher education continues to rise, so do the median salaries of recent college graduates. Unfortunately, with student debt reaching unprecedented heights, pay isn’t increasing as fast as is necessary for graduates to pay off their loans.

A study conducted by the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco established that between 2006 and 2013, the overall workforce saw a 15 percent increase in median salary, while recent college graduates only received an increase of six percent, according to the Los Angeles Times. It is an age-old paradox: the very education that could propel students into monetary success is creating additional years of financial burden. It’s clear that there is no easy fix to this discrepancy between tuition cost and salary increase, and some have suggested that college isn’t worth its high price.

The statistics, however, provide more context. College graduates overall are paid more than both high school graduates and those who obtain a GED. Its high price tag has created a sense of entitlement in students seeking jobs post-graduation, and with that, has reduced the meaning of the college experience to monetary results. Still, college continues to be a valuable life tool.

Americans are drawn to attending colleges and universities. There are so many in the U.S. that the U.S. News & World Report only provides rankings for roughly 1800 of them. High school students pack their schedules full of Advanced Placement and International Baccalaureate courses in addition to long lists of extracurricular activities, all in the hopes of impressing and gaining entrance into top-tier colleges. College Confidential, a web-based forum, lends tips and tricks about the college application process, embedded in the stress-induced conversations of high-strung parents and students. Numerous companies and businesses have risen out of this newfound higher education industry, including the Common Application, the College Board and the many college counselors and standardized testing tutors.

Nowadays, the college application process has transformed into a rite of passage for high school seniors. But with the craze comes a sense of privilege.

The entitlement is certainly understandable. After paying upward of $200,000 in college tuition and spending an additional four years in the classroom, graduates might feel they deserve something that rewards them for the money and hard work invested in their education. But entitlement and elitism go hand in hand, and in some cases the notion of elitism can start at the college or university.

With the use of technology and social media, colleges are able to market themselves favorably toward parents and prospective students in a way that is more accessible, in addition to their usual mailings and pamphlets.

Schools start a hypothetical arms race, however, when trying to attract students. Colleges and universities everywhere are building Olympic-size swimming pools, state-of-the-art research facilities, hiring world-renowned faculty members and even attracting celebrity professors.

It is hard to blame the universities for these additions. If their schools appear to be more desirable, a greater number of students will apply and the acceptance rates will decrease, making the schools more exclusive. With this mentality, it’s easy to see how college elitism has taken a new form in the 21st century. Higher education can no longer be exclusively for the extremely wealthy, but with a larger number of applicants, colleges themselves have become more elite institutions. More importantly, their graduates might feel entitled to a job over a peer who attended a “lesser” university or one who didn’t attend one at all. The modern day workforce, which drives consumerism, the economy and daily life, is populated with college graduates all vying for the same jobs. A college degree is no longer a distinguishing feature on résumés. Therefore the entitlement factor is no longer warranted.

The rising tuition fees and student debt, elitism and entitlement work together in a cyclical process. Critics say that a degree isn’t worth the financial hassle, which, in some cases, might be true. According to a 2013 Bureau of Labor Statistics study of people, the median weekly earnings for a bachelor’s degree holder age 25 or older is $1,108, versus $651 for a high school graduate. Strictly looking at degrees from a salary viewpoint, college continues to reap more benefits than a high school education can.

The perks of college, however, are not always tangible or monetary. Students take chances, learn from mistakes and define and develop their own values before fully heading off into adulthood. Though the four years spent at academia are a safety blanket with an investment price tag, a college education unlocks the door of opportunities and networks that would be difficult to obtain otherwise in addition to giving students the discipline necessary make smart choices in a world of opportunities.

Yet no one is entitled to education, jobs or money, and hard work is essential in order to succeed. This is the new American way, and college is here to stay.

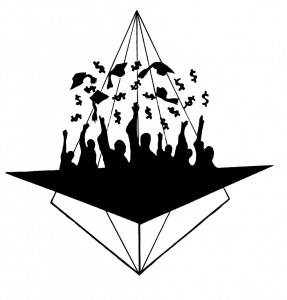

The question is what does the money go on? Not to the professors who teach you (ask your profs next time you get a chance), but to a bloated administration and to trying to run an educational institution like a business. And to paying for ridiculous facilities. Students need to raise their voices against tuition hikes, we need to start prioritizing our public universities again as motors of social mobility, and we need USC to focus on research and teaching, not shiny buildings and paying marketing people. It’s OUR university, not the administration’s.