Great books have the ability to change perspectives

We all read books for a variety of reasons, whether it be for pleasure, work or self-help. Sometimes, books pass through our hands and leave little impression on our memories. Other times we read something that sticks with us and, every now and then, changes our worldview completely. I tend to devour books faster than pizza, and though I’m not especially picky about what I eat, I rarely find a book that completely alters my mindset or opinion toward a certain issue. These books have shaped who I am as a person and taught me more than any history lesson.

1. The Grass Is Singing by

Doris Lessing

When I first picked up this book as a junior in high school, I knew very little about South African culture and apartheid. All I knew was that I wanted to read a book from a completely different society in an attempt to broaden my worldview. Lessing’s heartbreaking story not only opened my mind to this culture but also made me more aware of the horrors of this period in history. The novel chronicles the life of a young white woman, Mary Turner, growing up in segregated Rhodesia. After overhearing two women cruelly gossiping about Mary’s single status, her self-confidence plunges and she marries the next man she meets in an act of desperation. This man is Dick Turner, a poverty-stricken farmer. Mary’s new life in their farmhouse is marked by a rapid loss of independence that cripples her. She isolates herself from everyone around her except her black servant Moses, who she treats with contempt and outward racism. But, as her mental state takes a turn for the worse over the years, she comes to rely on and even care for Moses. The book ends hopelessly and tragically but full of Lessing’s beautiful language and sensitivity. There’s no lying that this book is heartbreaking all the way through, but the incredible humanity of the story and bare realities of apartheid make it well worth reading. This book not only taught me about a culture I knew nothing about, but also, more than any other book I’ve ever read, brought home the fact that no person, society or situation is ever black and white.

2. The Grapes of Wrath by

John Steinbeck

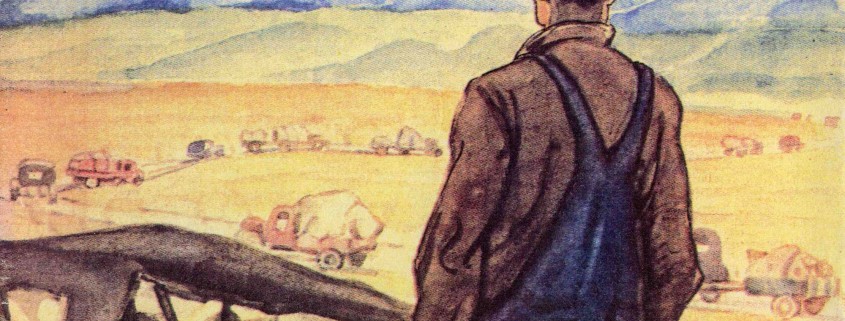

I read this book in the summer before my senior year of high school because I thought that bringing it up would sound impressive in a conversation. I must say that I wasn’t particularly excited about the prospect of an 800-page novel about the Dust Bowl and the Great Depression, and I set about reading it as if it were an assigned novel for English class. By about a quarter of the way through, though, I was hooked. More than that, I realized that this was a book that was going to change my outlook on life and history forever. Steinbeck’s realist focus is on the poor, unremarkable Joad family as they make the pilgrimage from their farm in Oklahoma to California in search of a new life. Before I read this book, I had always been of the opinion that exciting novels about distant places were, by far, the most interesting. Steinbeck taught me that the most incredible beauty and nobility can be found in the banal, in the tragic and in the world directly around us. His style of alternating chapters between the specific story of the Joads’ journey and a grand, bird’s-eye view description of the social and cultural movements happening in America at this time make for an enjoyable read. The writing is exquisite, the characters are real and the story of poverty, loss and hope continues to resonate across cultures and time.

3. We Need To Talk About Kevin by Lionel Shriver

This is one book I will recommend to everyone I know, regardless of one’s taste in literature. I have never met one person who didn’t praise this novel as one of the most momentous books he or she had ever read. Though, sadly, not nearly enough people have read it at all. While the film adaption starring Tilda Swinton as the distant mother of a mass-murdering teenager garnered some attention for the story, the book remains, in my opinion, infinitely better and much more complex. The story is told by letters from reluctant mother Eva Khatchadourian to her absent husband about their first child, Kevin. Inexplicably, Eva feels no maternal attachment toward Kevin, and secretly thinks he is a deeply disturbed and manipulative child. This lack of motherly love creates a rift between Eva and her husband, Franklin. The situation escalates, all leading up to Kevin murdering several of his classmates in the school gymnasium. Shriver’s psychological analysis leads the reader to question whether Eva’s distant parenting and clear distaste for Kevin affected his development and could even be partially to blame for his deadly actions. This book doesn’t sensationalize, nor does it brim with bloodlust and political posturing. Instead, it turns inward and examines how complex our various relationships are, especially within the family setting. This book made me think about parenthood as well as mental illness in a completely different light, all the while being fascinatingly entertaining.

Kirsten Greenwood is a sophomore majoring in English. Her column, “By the Book,” runs every Friday.