Researchers develop personalized learning robots for children with autism

Researchers in the Department of Computer Science studied interactions between socially assistive robots and children with autism in a monthlong in-home study to explore how robots benefit the children’s engagement and learning.

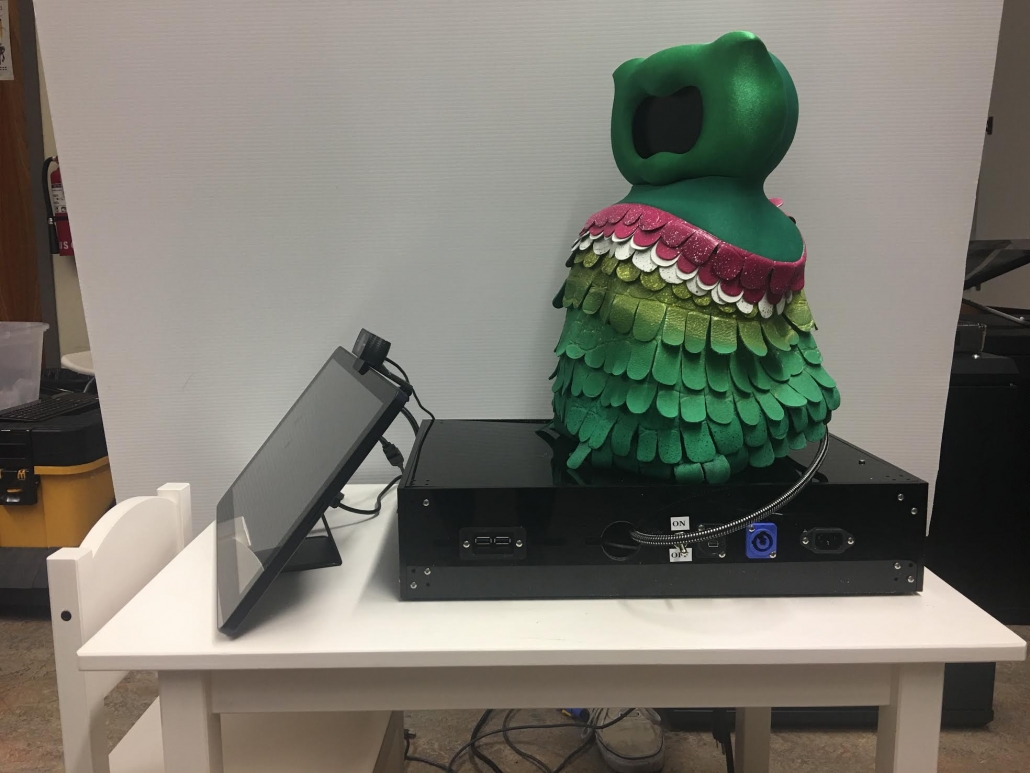

Gisele Ragusa, a Viterbi professor and co-principal investigator on the project, said researchers designed Kiwi, the robot, to be warm and fuzzy but durable. They did not want a robot that made a lot of noise because many children with autism spectrum disorder have trouble handling too many stimuli at once. Kiwi is gender-neutral, since researchers wanted to ensure that the children could decide for themselves and identify with the robots’ genders.

“I was that person who was involved with every single family, start to finish,” Ragusa said. “It was really a great experience for me –– one of the most dramatic research experiences that I’ve ever seen because the children did so well.”

During the deployments, the children played simple math games on a tablet nearly every day for 30 minutes. Kiwi sat behind the tablet and provided feedback and instruction about the game while recording the interactions.

Shomik Jain, a senior majoring in applied and computational mathematics and pursuing a master’s degree in electrical engineering, said the games adjusted to each child’s learning patterns. For instance, if the child was doing well, the team would present them with a more advanced game.

“We would love to see socially assistive robots deployed in the homes of children with autism, especially to augment therapists when they may not be available or affordable all the time,” said Jain, a lead author on the project. “It’s really important to analyze studies in these real-world environments.”

Following the deployments, Jain looked at each child’s disengagement and decided whether it could be modeled by using data that the team collected, including the child’s visual focus of attention and audio data.

“We wanted to model the child’s behavior to see if we could create smarter, more intelligent robots,” Jain said. “We want the robot to be able to recognize and respond to changes in emotion and behavior, such as if the child becomes disengaged.”

According to Ragusa, parents told researchers that over time, their interactions with their children increased as the children developed a relationship with Kiwi. Maja Mataric is a lead investigator on the project and has worked with deploying robots into the homes of 17 children between the ages 3 and 8 with mild autism from late 2017 to 2019. Mataric has also been involved in research focused on finding ways for robots to help children with autism and other people with neurological conditions.

“In this era of concerns about [artificial intelligence] and robotics taking people’s jobs away, it is important for people to see various ways in which technology can do good,” Matarić wrote in an email. “Socially assistive robotics is a great area for doing good for humanity; it is also a great area for engaging typically underrepresented groups in computing and engineering.”

Ragusa said she believes socially assistive robots are a perfect match for children with autism spectrum disorder.

“Autism is a mysterious challenge,” Ragusa said. “We know far less about autism spectrum disorder than we do other learning-related disabilities or other challenges, so the need was great. We were using something that was socially assistive by definition, since individuals with autism spectrum disorder primarily have social challenges.”

According to Jain, the socially assistive robots are not intended to replace human therapists but rather to augment or supplement them.

The study was funded by a five-year National Science Foundation grant awarded to a collaborative team from USC and other universities, including MIT, Yale and Stanford. The grant was designated for research to develop socially assistive robots for children.

“I think when you think of an issue, such as the social development of kids with autism spectrum disorders, your first thought isn’t, ‘Let’s give them a robot to interact with,’” said Roxanna Pakkar, a research assistant on the project and senior majoring in electrical engineering. “It’s cool that the engineers in our labs and the psychologists that we work with and educators that we work with were able to come together and develop this solution.”