USC students launch satellite

As Morgan Farrier watched the Jan. 13 launch of USC’s third satellite, Dodona, riding on SpaceX’s Transporter 3 mission, she saw her contributions since last spring become a reality. Farrier, a sophomore majoring in astronautical engineering, worked at the project’s Marina del Rey ground station in mission operations to create the satellite that would hitch a ride to orbit as part of SpaceX’s Smallsat Rideshare Program.

Dodona is a project directed by research professor David Barnhart from the Space Engineering Research Center, a joint research center within the Viterbi School of Engineering Department of Astronautical Engineering and the Information Sciences Institute.

“Part of the mission of the SERC [is] to do advanced research in various space engineering disciplines, at different levels,” Barnhart said. “I refer to [SERC] as a space engineering teaching hospital because it’s intended to give students hands-on experience that they normally potentially wouldn’t get during their academic curriculum before they go out into industry or government to do it full-time.”

Partnered with the aerospace company Lockheed Martin, a group of undergraduate and graduate students working alongside employees at SERC undertook Dodona to integrate an internally built Cubesat mini satellite that was the size of a bread box — 10 centimeters long and wide, and 30 centimeters high — to test Lockheed Martin’s newest payload technologies in orbit. This technology is part of Lockheed Martin’s larger La Jument program, with Dodona being the first in a series of demonstration flights.

“Our job is to build a satellite for them, essentially, make sure that payload gets into space, points where it needs to point and then can bring its data back to the ground, and we can talk to it from the ground,” said Julia Schatz, a graduate student studying computer science and aerospace engineering who works at SERC.

The course of the year-long project was beset by multiple challenges. In addition to a myriad of technical difficulties and the students’ incomplete knowledge of satellite integrating, the coronavirus pandemic was the most serious of them, Barnhart said. Collaborators were prohibited from entering the laboratory as the time got closer to Jan. 13, the confirmed launch date.

When Barnhart’s team obtained approval to return to the laboratory, there were protocols put in place for personal protective equipment, which brought new challenges to team members as only two of them could work, six feet apart, in the laboratory.

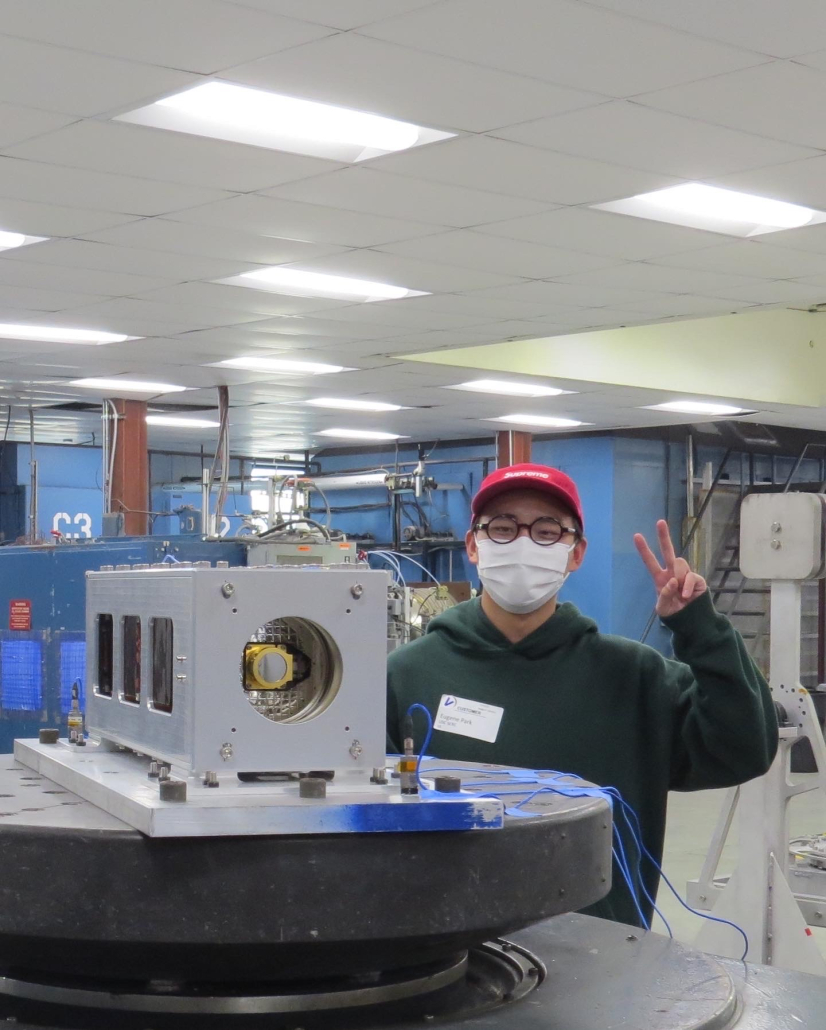

“The biggest hurdle that we had to face was because we’re working so close together; working apart six feet or making sure that there’s only two people in the lab was very difficult to actually just get progress, to actually get stuff done,” said Eugene Park, a masters student studying electrical and electronics engineering and engineering/industrial management.

Under stringent coronavirus-related protocols, the project progressed at a much slower pace than expected, and the team’s timeline to test and integrate the satellite was also greatly compressed. It wasn’t until August, Park said, that the project “really started to pick up.”

“In the case of the satellite, there is a marker in the sand called the launch date,” Barnhart said. “You can’t miss the launch date.”

During the project, student researchers commuted nearly an hour to Marina del Rey, which required them to carefully balance their time when coping with different class schedules and other time commitments.

“Luckily, we had a strict rule of at most 16 hours a week, so even if people really want to volunteer, we want to make sure you get your minimum done, but also that school was a priority,” Park said.

Plowing through multi-layered obstacles brought by the coronavirus pandemic, including accommodating student researchers of different class schedules into the lab and observing protocols against transmission, Barnhart said he utilized the project not only as a research program, but also as an educational opportunity for student researchers to gain a deeper understanding of the space engineering industry.

“The challenge, obviously, is to put in practices and techniques and procedures to minimize the potential risk and offer opportunities for [the student researchers] to learn as much as possible,” Barnhart said. “Because, again, most students haven’t done this before … It gives them a grounding and it also gives them confidence.”

The launch of the satellite did not mark the end of the project. Collaborators on Dodona continue to closely monitor the deployment of the satellite and communicate with it at the ground station.

“Our next goal is to make sure that, once it detaches from that satellite, it actually does its job — it turns on properly, we’re able to communicate with it, take pictures [and] send messages back and forth,” Park said.