50 years of Title IX

Content warning: This article includes mentions of sexual assault and gender-based violence.

“No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.”

These 37 words, written in 1972 as part of Title IX of the Education Amendment the same year, transformed the landscape of higher education. No longer could institutions receiving federal funding legally discriminate against students on the basis of sex — as President Richard Nixon signed the bill into law, equity was set to be achieved and space was created for non-men in collegiate education and athletics.

While Title IX outlawed school-sanctioned gender-based discrimination, instances of gender-based harm on college campuses, including sexual assault and gender-based violence, continue to disproportionately affect non-men: According to nationwide statistics from the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network, 26.4% of women undergraduates experienced rape or sexual assault compared to 6.8% of men undergraduates. More than 23% of transgender, genderqueer and gender nonconforming students have been sexually assaulted.

While critics have debated Title IX’s application to collegiate athletics since the bill was first signed into law, the policy undoubtedly increased spending and participation rates for women’s sports teams. And yet, inequalities remain: the NCAA Title IX at 50 report showed expenditure rates to be 23% higher for men’s Division I collegiate sports compared to women’s teams of the same division.

The Daily Trojan spoke with students and faculty about Title IX policy at USC through the years — from triumphs to scandals — and their hopes for the years ahead.

History of Title IX legislation

Over the storied history of Title IX policy, a handful of amendments were proposed and several lawsuits brought against the legislation. Sen. John Tower proposed in 1974 the rejected “Tower Amendment,” which would’ve exempted revenue-producing sports from complying with Title IX. Two months later, Sen. Jacob Javits proposed an amendment to provide for “reasonable provisions considering the nature of particular sports,” arguing that sporting events and uniform spending for sports with larger crowds need not be matched in sports with smaller audiences.

The final version of Title IX, signed by President Gerald Ford in 1975, included Javits’ amendment. The congressional review of this version rejected multiple attempts by senators to disaffiliate the legislation from athletics — including Sens. Paul Laxalt, Carl T. Curtis and Paul J. Fannin’s 1975 disapproval of Title IX’s application to intercollegiate athletics.

The NCAA filed a later-dismissed lawsuit against Title IX in 1976, challenging its legality. Colleges and high schools were given until 1978 to begin fully complying with the legislation — USC began complying in 1972.

The U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights outlined in 1979 a test to determine a school’s compliance with Title IX, particularly within the realm of athletics. The test’s three areas are: whether the school awards scholarship money to men and women proportionally with participation rates; whether schools accommodate athletic interests and abilities, such as by providing athletic participation opportunities proportionate to enrollment; and whether a school provides equitable access to equipment, practice times, support services and other areas.

The 1984 Supreme Court decision in Grove City College vs. Bell temporarily ceased Title IX’s application to athletics; Congress passed the Civil Rights Restoration Act four years later over President Ronald Reagan’s veto, stipulating that Title IX involves all operations of institutions receiving federal funding.

EEO-TIX at USC

The USC Office for Equity, Equal Opportunity, and Title IX was established ahead of the 2020-21 academic year as a “centralized report and response office that provides consistent and equitable access to supportive measures and informal and formal resolution options,” the EEO-TIX site reads.

EEO-TIX was created as a merging of two formerly separate offices — the Office of Diversity and Equity, and the Office of Title IX. The combined office deals with all protected class issues, including those of sex, gender, race, disability, ethnicity and religion.

Title IX Coordinator and EEO-TIX Vice President Catherine Spear joined the office in August 2020. Spear saw the office double in size since she began, with an increase in supportive measures and dedicated resources toward messaging and raising awareness among the University community about rights and responsibilities relating to the policy on prohibited discrimination, harassment and retaliation.

“We’ve continued to enhance what we call the investigation and resolution side of our team, where we’ve added new resources and focus has been leaning in with care for our community members, recognizing whatever brings them to our office, especially if they go through a formal process,” Spear said.

Reporting an instance of sexual assault or discrimination is stressful, Spear said, and can add to trauma the individual may be experiencing, so EEO-TIX created a dedicated intake support and care team.

“Even without a filing of a formal complaint, our care team can help facilitate, connecting that student to support resources — that may be connecting them to the ombuds, to RSVP [or] it may be with their permission reaching out to their faculty to help secure them a reasonable accommodation in the form of an academic adjustment, such as an extension of time on a test,” Spear said.

In the formal resolution process, the state of California requires individuals to go through a hearing and be available for questioning if they want to be considered a party or witness in the process. This, she said, can be a lot to ask, and some parties might elect not to do so — meaning their statement and provided information may not be considered by the hearing officer.

Today: Sexual assault reports and prevention

The USC Title IX office concluded in September 2021 that former Song Girls coach Lori Nelson harassed and body-shamed several former members from 2016 until she resigned in 2020. In April 2020, a former USC student filed a lawsuit with Title IX accusing former Marshall School of Business professor Choong Whan Park of sexual assault, specifically toward female student assistants of Korean descent. The lawsuit claimed that USC was aware of the harassment and discrimination; however, the University denied the allegations.

Forty-eight gay or bisexual former patients of former USC physician Dennis Kelly came forward in 2019 saying that Kelly sexually abused them. The University administration received complaints about the physician’s behavior in the four years prior to his departure. Two years prior, the University allowed George Tyndall — a former USC gynecologist who unlawfully penetrated and violated his patients — to resign without telling law enforcement or medical authorities about his actions.

“[We] concluded that USC violated Title IX by failing to promptly and equitably respond to notice of nine complaints by patients of potential sexual harassment during medical examinations between 2000 and 2016, and that that failure may have allowed patients to be subjected to sex discrimination,” the U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights wrote in a summary of their investigation of the incident.

In February 2020, U.S. District Judge Stephen Wilson approved a $215 million federal class action settlement, resolving the claims of more than 18,000 women who Tyndall treated. The University, along with the 710 women who filed cases surrounding Tyndall reached an $852 million global settlement in March 2021.

Between Sept. 25 and Oct. 20, five to seven incidents of drugging and sexual assault at the Sigma Nu fraternity were reported to DPS. The University failed to disclose the reports to the USC community until a campuswide email was sent Oct. 20. Five additional reports at Sigma Nu, Phi Kappa Tau and other undisclosed locations were later reported and shared with the community.

“USC is one of the institutions that is kind of guilty about or guilty for creating rules that protect some more than others. In the past year, we’ve seen a lot of issues on sexual assault in the USC community, and just it’s been kind of wild to see who these rules are helping,” said Kat Lara Fuentes, a junior majoring in psychology and health and human sciences.

Fuentes said that as a woman in STEM, she feels she has not been treated with the same respect as her male classmates. Additionally, she said there are loopholes and safeguards for people who do not want to be impacted by Title IX rules.

“In the [reporting] process, a lot of people are just being traumatized further, or silenced further than when they originally started … The identities of the perpetrators are being so protected. Meanwhile, the victims are just not being listened to, and it’s kind of making it harder for us to want to speak up,” Fuentes said. “We’re asking for transparency and accountability.”

President of USC Flow Piya Garg, a junior majoring in international relations and global business, said the organization encourages solution oriented discussions about sexual assault at the University. The “slowness” of the Title IX office, she said, stalls progress toward these solutions.

“The Title IX office in the University doesn’t already create an environment where people feel comfortable to do that to report, and while it’s so great that USC is taking this time to celebrate Title IX, isn’t it a bit hypocritical that the University hasn’t even really acknowledged once its role in perpetuating that same unsafe environment that the core of Title IX opposes?” Garg said.

Rev. Najuma Smith-Pollard, an assistant director of public and community engagement for the Center for Religion and Civic Culture in the Cecil Murray Center, noticed a lack of dialogue surrounding sexual assault in religious spaces. A member of the ministry since 1996, Smith-Pollard spoke with survivors of sexual assault and created a sexual violence awareness and training campaign titled “It’s Not Okay.”

“There was very little dialogue, but there were a number of people who were having experience within the church,” Smith-Pollard said. “The impetus for all of it was just my own personal experience … recognizing that the church had very little resources for people.”

“It’s Not Okay” offers training for faith and community leaders on speaking about sexual violence and raising awareness about the bias against those who report sexual assault or discrimination among church-going populations. Since many churchgoers have preconceptions about or personal experience with sexual violence, Smith-Pollard said, it’s important for religious leaders to open conversation up in a spiritual context to offer support.

“Even though sexual assault is a difficult conversation to have, for anybody, it is necessary that faith leaders of all kinds have these conversations because people in the congregation inevitably have been impacted,” Smith-Pollard said. “[Sexual violence] is so pervasive that you can’t even get 20 people in a room without at least two or three people having direct impact.”

Sexual assault is prevalent on almost all college campuses — and USC is no exception. Nationally, an average of one in four female undergraduates reported experiencing sexual assault. At USC, that average nearly stands at one in three, according to a 2019 survey conducted by the Association of American Universities Survey on Sexual Assault and Misconduct.

The U.S. Department of Education’s Campus Safety and Security program reported 114 instances of rape on campus in 2018, a number that has since fallen to 38 instances in 2019 and 24 in 2020 — the most recent data publicly available.

A common misconception about Title IX, Smith-Pollard said, is that reports are centered on retaliation. She argued that Title IX has, in fact, given victims of sexual violence the opportunity to protect themselves. Title IX policy has made a tangible impact on students’ education and feeling of security in higher education, she said.

“[Prior to Title IX] was a time where students, particularly girls, were on campuses having all kinds of experiences happen to them … and it impacted their ability to perform,” Smith-Pollard said. “Title IX, from what I’ve seen, helps those who are directly impacted — who have an incident or an attack, a violation — the educational opportunity to remain in school and remain in their program but still have some safety net that they can go to.”

Student Health and sexual assault prevention

Following a compliance review of Keck Hospital of USC’s sex discrimination response policies by the U.S. Department for Health Services’ Office of Civil Rights, the parties reached a voluntary agreement June 17. The agreement includes a new policy for sensitive health exams, during which authorized members of the healthcare team will need to be present.

Keck Hospital also agreed to retain positions of Title IX Coordinator and Deputy EEO-Title IX Coordinator for Healthcare, conduct staff training and a number of reforms, too, following the George Tyndall scandal. Changes included integrating Student Health into Keck for greater oversight of standards of care and creating new methods for collecting information about potential medical and sexual misconduct.

Equality in athletics

Many attribute the establishment and growth of women’s collegiate sports to the implementation of Title IX policy nationwide.

“I don’t think you can underestimate the importance of the women leaders in Title IX and the diversifying of our sports led by some of those pioneers in what we see today,” said President Carol Folt during the celebratory event, Title IX: 50 Years of Progress, held in June.

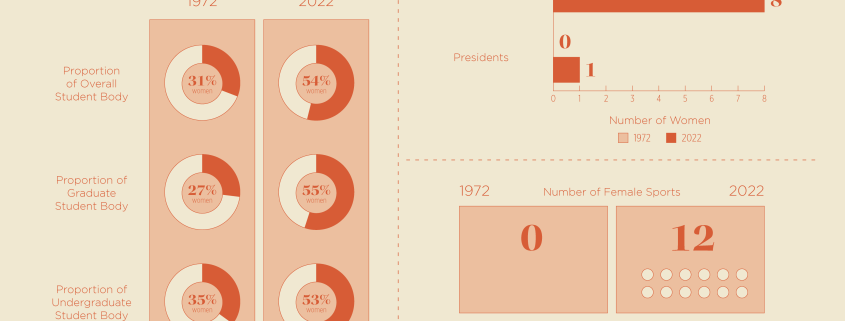

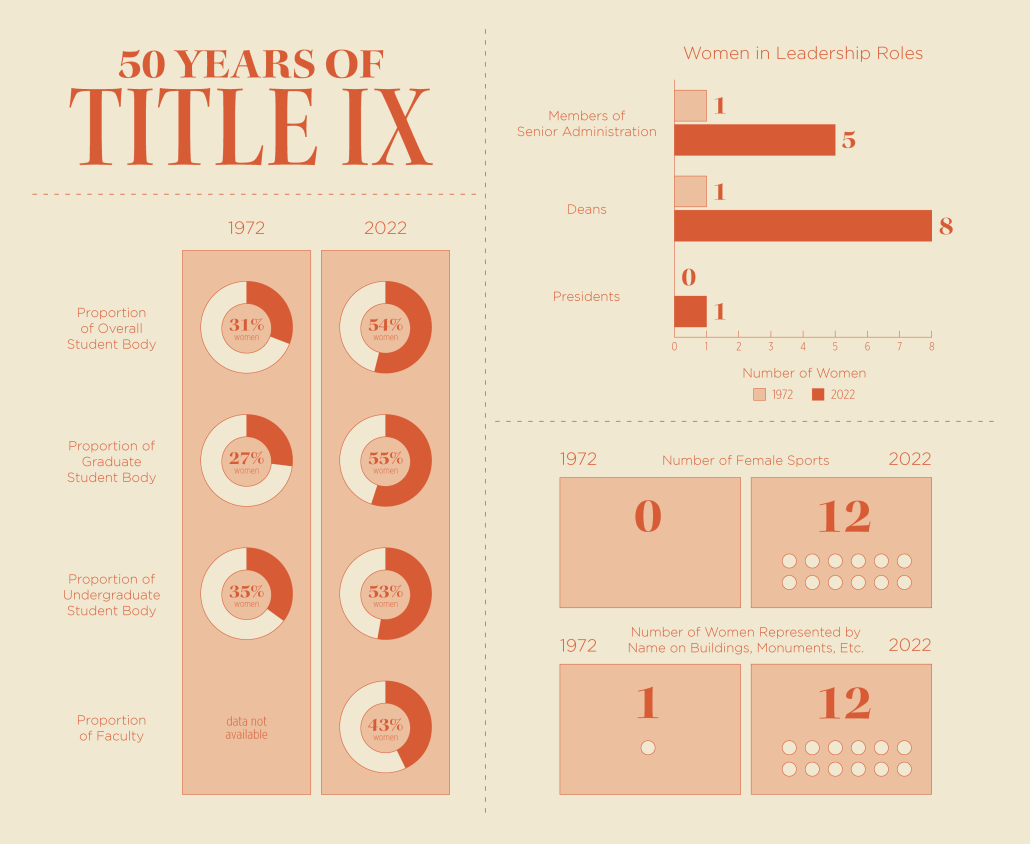

In 1906, the National Collegiate Athletic Association was created to regulate men’s football and cemented its position as the primal regulatory body for college athletics. Prior to Title IX, women had no access to athletic scholarships or the right to hold championships for women’s sports teams. In 1972, the ratio of collegiate women to men participating in sports was 3:17 — an inequality compounded by disproportionately poor facilities, supplies and funding for female athletes.

USC women’s soccer goalkeeper Talia Grossman, a junior majoring in fine arts, was invited to speak at the June event and introduced Folt.

When she was first asked to speak in front of alumni and faculty, Grossman knew she wanted to participate because she viewed the opportunity as a chance to advocate for soccer.

Her interest in advocating for the equal treatment of women athletes and traditionally-favored male athletes originates from having coaches underestimate her in her childhood. Even though she loved playing baseball as a kid, playing a male-dominated sport and the pressure to succeed as a female athlete weighed on Grossman from a young age.

“It’s a heavy weight to hold because you’re representing all womankind, and at some point, baseball wasn’t as enjoyable anymore,” Grossman said in an interview with the Daily Trojan. “I really love baseball, it’s not just because I felt like I had to play, but there definitely was a pressure when I was young to keep on playing because I didn’t want to be that girl who stopped playing because the guys are getting bigger … and stronger now.”

As an example of the disparity between the treatment of male and female collegiate athletes, Grossman pointed to how the USC women’s soccer team wasn’t allowed to host an audience at their final rival game against UCLA, while the USC men’s football team was designated a “bunch of fans” at their scrimmage last November. Although Grossman noted that USC football brings in great acclaim for the University — the program has created $50,046,008 in revenues and $17,921,486 in net profit — she said it doesn’t “feel great” as a female athlete.

“The high profile men’s sports, most notably football, get a disproportionate amount of resource support,” Grossman said. “To be fair, it’s a tough balance to strike because football, in particular, generates so much revenue for the University, but nonetheless, I think there is an opportunity to shift the balance a bit so that more resources are devoted to women’s sports.”

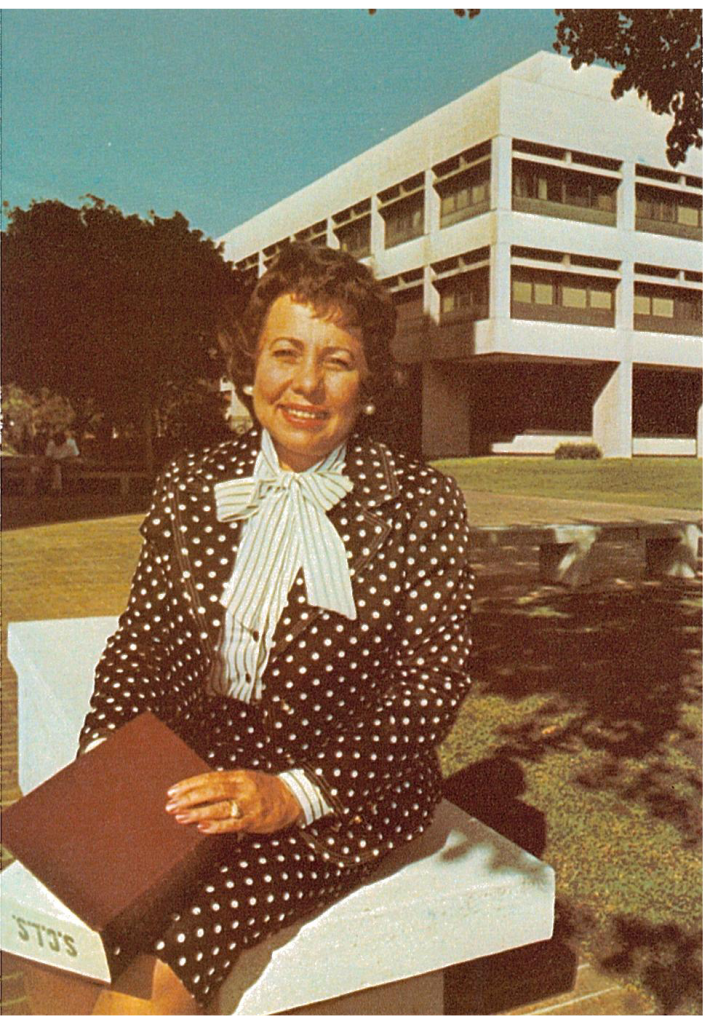

In her 18-year tenure as associate athletic director and later senior associate athletic director, Barbara Hedges was instrumental to the growth of women’s sports at USC. Hedges began at USC Athletics in 1973, one year following the signing of Title IX, and her team was chiefly focused on moving women’s sports “forward and upward.”

“The overall goal was to provide the same opportunities to our female athletes as their male counterparts,” Hedges said. “That included scholarships, travel, recruiting, upgrading coaching, upgrading scheduling of different athletic schools that are our athletic competition across the country.”

Every year, Hedges said, the department added scholarships, increased the budget and improved women’s sports programs. Hedges witnessed the cultural impact of Title IX policy from the start, and said she’s seen as Title IX affected “every female in higher education.”

Associate Athletic Director in charge of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Julie Rousseau said her role at Athletics is centered on upholding the mantra: “Here you belong.”

“We’re focused on making sure that we are creating a space where people have a sense of belonging, and that they know that they’re included, and so that’s my job is to help create a space where our student-athletes and our staff have a space where they feel like they’re seen, they’re valued,” Rousseau said.

In the time she’s been with Athletics, Rousseau said the department has evolved in some ways — it held implicit bias conversations last fall, partnered with the School of Cinematic Arts and Theater of the Oppressed to create vignettes acted out by student-athletes and staff depicting microaggressions, and expanded modules. Athletics added two new mandatory modules for the 2022-23 academic year, one of which will focus on the LGBTQIA+ community and will include topics of implicit bias and preventing microaggression training.

“Obviously, things don’t always go as fast as you’d like. But I do think that there’s been some common knowledge, common language that we’ve developed; common understanding,” Rousseau said.

The future of Title IX

The U.S. Department of Education proposed regulations June 23 that would expand the policy’s protection to include gender and gender identity. The measures would ensure protections for LGBTQIA+ students from discrimination based on “sexual orientation, gender identity and sex characteristics.” They would also clarify and confirm protection from retaliation for students, employees and other school community members who report or otherwise exercise their Title IX rights.

The proposed regulations’ impact on athletics has not yet been addressed, and the DOE invites public comment on the measures.