British court values human rights over diplomacy

Last week, the British court ruled in favor of releasing US intelligence documents on Guantanamo Bay torture cases, sparking an international uproar. Of course, there are the real-world issues of whether or not releasing the documents could compromise the “special relationship” that Britain enjoys with the United States.

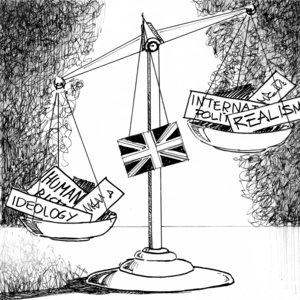

More important in this case, however, is the question of ideology. On one side of this argument are the champions of human rights; on the other, those who stress another principle: the inviolability of intelligence sharing between nations.

Ultimately, the release of these documents is not something the United States should hold against its British ally.

It’s important not to neglect the very real — if unspoken — factor of British humiliation. These documents are not dealing with American torture alone; rather, they are said to provide evidence in the case of Ethiopian-born Binyam Mohamed, who spent four years in Guantanamo Bay penitentiary and claims that British authorities colluded with Americans in his torture when he was in Morocco.

The British High Court decided to release the documents based on overwhelming public interest in the material. The judges felt it more important to come clean on the issue of torture than to uphold the principle of absolute secrecy in intelligence sharing.

The British government, however, is adamantly denying the torture allegations and swiftly appealed the court’s decision. The documents will not be released until that appeal goes through the courts.

Because the world already knows that the United States has committed torture in Guantanamo, no one will be shocked by the secrets revealed in the documents. If Britain had released these papers before the United States owned up to its own breaches of international law, then the principle of secrecy in shared intelligence would have been severely compromised. Britain’s national security would have been negatively affected, as foreign allies would no longer be willing to share information.

But most observers will agree that Britain’s national security will likely not be compromised in this instance.

The United States chose not to reveal those documents that would incriminate Britain for the sake of the alliance, not because it maligned America’s image in any way.

After all, it would be difficult to produce any new information more damning than the images and papers released from Guantanamo Bay and Abu Ghraib.

Despite the relative insignificance of the actual information in these documents, American officials seem to be just as eager as the British government to protect the principle of secrecy — regardless of how it might compromise human rights.

Last July, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton informed British Foreign Secretary David Miliband that any breach of confidence would be considered a violation of intelligence-sharing codes. She also threatened that the United States would consider cutting security cooperation with the Britain.

Clinton is taking a hard-line approach to the issue because it fundamentally challenges her perceptions of how intelligence-sharing operations should be conducted. This case is an exception to the rule in that Britain’s reasons for releasing the information are domestic; it is not setting any true precedent for future intelligence policy.

And no matter what threats she may throw around, Clinton is not in a position to cut ties between Britain and the American intelligence community.

Britain is America’s closest ally; the information they can provide in the future is too valuable to be lost over this case.

Representatives of the British government have argued that they have no problem with releasing the documents, as long as US authorities are the ones to take that step.

Actually, this situation would have worked out very nicely for the British government, if it weren’t for the courts. Because Britain denied torture allegations, its public image will be severely compromised if the documents prove otherwise.

So, if everything had gone according to plan, not only would Britain have maintained its moral superiority over the United States and prevented a negative opinion abroad, but it also would have prevented any ill will across the Atlantic.

Unfortunately for Britain, the High Court chose moral ideology over realism and put human rights before international politics. It seems unlikely that they will change their position, unless the United States takes more dramatic steps — seriously threatening the shared-intelligence relationship.

If US officials do take such measures, it won’t be to anyone’s benefit. Besides, it’s about time the United States made human rights a priority.

Rosaleen O’Sullivan is a junior majoring in English and international relations. Her column, “Global Grind,” runs Mondays.

Rosaleen, your youthful enthusiasm for “human rights” is admirable but misguided. The last line of your article beautifully illustrates your ignorance. The United States has a far better record in “human rights” than any other country in recorded history, which is in fact a part of why so many people keep wanting to come here, illegally or not. “Human rights” is a far bigger issue, and encompasses a helluva lot more, than whether military officials went a little too far in trying to protect the “human rights” of all us of after 9/11.