Global watchdog oversteps bounds

There are a lot of theoretical arguments these days about how much power non-state actors can legitimately wield in a globalized world.

Last week, a panel of French judges made a decision strongly in favor of traditional sovereignty, throwing out a case led by Transparency International and human rights group Sherpa before its first hearing.

Transparency International is renowned worldwide for its important work in monitoring global corruption. It rates political bodies around the world on everything from their level of democratization to their national systems, not to mention the calculations made on its infamous global corruption barometer.

Yet when the directors of TI decided to go head-to-head in court with three African leaders, they vastly overstepped their boundaries.

The case revolved around President Denis Sassou-Nguesso of the Republic of the Congo, President Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo of Equatorial Guinea and the recently deceased former President Omar Bongo of Gabon, all of whom were accused of embezzling national funds.

The three leaders denied the charges, though there is substantial incriminating evidence that this was the case.

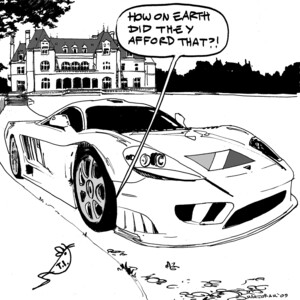

Particularly important is the fact that each owned luxury cars and homes in expensive parts of Paris and on the Rivera, purchases TI argues couldn’t possibly have been made with their legal salaries.

But why these particular leaders? Why now? Surely corruption exists within a large number of governments, many of whose leaders are exploiting their states’ resources and committing more flagrant acts of corruption than these three.

None of these countries’ human rights records compare to that of Sudan, Angola, Burma or North Korea, just to name a few states known for their extreme corruption.

In fact, it’s likely that TI chose to attack these particular leaders because their history and current political climate happened to support TI’s broader goals.

Right now, non-governmental organizations are challenging the system of sovereign states, seeking to find new ways to increase their legitimacy and power. Taking these men to court would have been an important breakthrough in altering the existing international power structure in favor of non-state actors.

Of course, TI knew better than to take on a leader whose response could have significant political repercussions. No matter how much corruption occurs in Angola, for instance, no one is going to step in because of its oil resources.

Similarly, no one will seriously challenge North Korea, because of the threat of nuclear weapons. The same holds for other corrupt — but strategically important — regimes.

The leaders of these three states were particularly easy targets thanks to their colonial history. As members of the Francophonie, they share a common French colonial history.

And, although Gabon is one of the most prosperous countries in the region, and Equitorial Guinea has high hopes for its developing oil resources, none of these states are particularly important on a global scale.

TI thought the French courts would be willing to take this case because of France’s historically paternalistic relationship with its colonies and the fact that a large part of these leaders’ wealth was held within French territory.

And so, because purchases were made in France, the French are implicated by proxy in the embezzlement of these states’ public funds.

This complication meant that if the French court initially rejected the case, it would be refusing to acknowledge its own country’s failures, a troubling prospect for any national judiciary.

So when the case was first presented in May, the court agreed to take it on. Fortunately, its position changed with further consideration.

It is certainly true that corruption is a terrible problem and there should be some way of forcing corrupt rulers to face justice. But this is a problem for the United Nations to resolve most likely through the International Criminal Court — not a group of activists.

A trial in a foreign national court, by a non-governmental organization, is truly a slap in the face to any sovereign ruler.

Africa’s leaders deserve the same respect that heads of state in any other part of the world would demand. That Transparency International and Sherpa would have the audacity to publicly take such an obviously discriminatory step is as much a reflection on the system as it is upon their poor judgment.

Transparency International issued a statement on its website promising to appeal the French court’s decision, stating that the decision “only demonstrates how much further the French legal system has yet to evolve in order to allow specialized organizations to fulfill their rightful role.”

The group’s tone is petulant and self-important; however, it’s important to remember that the members of Transparency International do have the best of intentions. Now they just need to learn their place, which undoubtedly rests somewhere far below that of national leaders — even those whose actions we cannot approve.

Rosaleen O’Sullivan is a junior majoring in English and international relations.