Panel discusses Sochi Winter Olympics

On Tuesday, a panel of experts discussed the potential impacts of new Russian legislation criminalizing lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender activity on the 2014 Sochi Olympics.

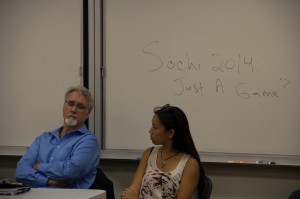

History lesson · Associate professor Robert English speaks to student Emily Huang about the consequences of anti-gay legislation in Russia. – Dasha Kholodenko | Daily Trojan

Panelists included Daniel Durbin, founder and director of the USC Annenberg Institute of Sports, Media and Society; Professor Robert English of the USC international relations department; and Emily Huang, a junior majoring in sociology and co-president of OUTreach.

The panelists looked back at similar situations in which a country has been dissatisfied with the host of the Olympics, and noted multiple failures to boycott the games.

In 1980, the United States boycotted the Russian Olympics because the country had just invaded Afghanistan, but the United States’ boycotting efforts were looked at as “ineffective” by the public. Many Americans reviewed the decision as one of President Jimmy Carter’s worst.

“It is often much more effective to go out to the Olympics and present your position either subtly or overtly,” Durbin said.

One of the problems with athletes publicly taking positions, according to the panelists, is that the Russian media almost never publishes any pro-gay rights statements by athletes, especially those from the West.

Despite intolerant policies in the country, international gay athletes might not need to worry about the Russian government trying to kick them out of the country for showing signs of homosexuality.

“It’s going to be almost impossible for Russia to say that these athletes are involved in propagandistic activity and kick them out of the country,” Durbin said.

Under Russian law, “homosexual propaganda” is outlawed, but exactly what that means is still under review in the country.

According to English, an expert on Russia and a former resident of the country, Russia should not be expected to be overly forceful during the time of the Olympics, especially considering that it is essentially the International Olympics Committee who has the power to decide who stays and who goes.

English noted that a lot of President Vladimir Putin’s anti-gay legislation stems from a late 1990s movement toward “Russian nationalism,” a movement toward the return of Russian roots, which is strongly supported by the Russian Orthodox Church.

“[The legistlation is] not admirable political leadership, but neither did [Putin] start it,” English said.

Even before Putin became president, groups in Russia were forming and demanding reform. According to the panel, these groups came about as a result of a poverty epidemic in Russia during which citizens fought for moral causes in an attempt to preserve their dignity.

Russian nationalist groups have also targeted Westerners, foreigners and women, as well as LGBT people. The experts pointed out that citizens of troubled countries often find scapegoats for their problems. Inequality in sports has also been a lasting issue.

“Sports have been gendered since our nation began,” Durbin said. Even in America, athletes faced segregation by race, gender and sexual orientation.”

Alec White, a sophomore majoring in political science, was upset that the Olympics were not moved out of Sochi in light of the anti-gay legislation, but also that countries such as the U.S. and France were not able to offer alternatives to boycotting the Russian Olympics.

“It would have been a great idea if this [anti-gay law] came up a little sooner,” White said. “Vancouver [would have been] a good compromise because you wouldn’t have the athlete’s dreams shattered.”

Follow Morgan on Twitter @megreenwald

Was that an attempt at the worst photo ever?