The Eck’s Factor: Why anti-racism is necessary for white allyship

“Sometimes, you need to scorch everything to the ground, and start over. After the burning the soil is richer, and new things can grow.”

In her 2017 novel “Little Fires Everywhere,” Celeste Ng chronicles the intertwining of two families in a “progressive” suburban neighborhood during the ’90s. Recently adapted into a television show starring Reese Witherspoon as Elena Richardson and Kerry Washington as Mia Warren, the franchise tackles themes of adolescence, motherhood and race — and of course, fire.

Both the racial tensions between white landlord Elena and Black single mother Mia and her daughter Pearl and the show’s symbolic use of fire parallel the contemporary racial climate.

On May 25, a viral video surfaced of a police officer killing 46-year-old George Floyd in Minneapolis. The officer is seen digging his knee into the neck of Floyd, as Floyd begs, “I can’t breathe. Please, the knee on my neck.” Floyd died shortly after.

While the coronavirus has only posed a threat since late 2019, the United States has been plagued by racial profiling and police brutality for much longer. This phenomenon cannot be traced to one specific point in time; rather, it reflects the foundations of American society — the same ones that implemented structural racism through slavery and the same ones that provoke us to differentiate between racism and anti-racism.

According to Alberta Civil Liberties Research Centre, “Anti-racism is the active process of identifying and eliminating racism by changing systems, organizational structures, policies and practices and attitudes, so that power is redistributed and shared equitably.” This is distinct from being “not racist,” which translates to being ignorant of the differences between racial groups. Being “not racist” is complicit in white supremacy and is actually racist.

To contextualize this difference, Elena and her children epitomize the “woke” white person who insists they understand racism but whose perspective merely scrapes the surface: They perceive racism as the mere unfortunate fact that not all races are treated equally — a form of complacency that disregards the complex and nuanced experiences of marginalized communities.

This lack of robust understanding manifests in the form of comments like, “I don’t see race because everybody should be treated the same.” This white, “progressive” family’s perception of racism starkly contrasts the reality of the United States’ racial environment, highlighted by Warren as its proxy, from her disapproval of the Richardson children’s lavish and privileged lifestyles to her discomfort and nervousness regarding the police.

In one scene, Pearl and Moody (Elena’s son) are caught trespassing in a junkyard, and a neighborhood watch officer takes them home. Mia chastises Pearl, remarking how she could have died. Elena, overhearing their conversation, chimes in with, “I think you’re overreacting.”

These interactions are laced with microaggressions and encapsulate the modern binary between racism and anti-racism. Racism does not exclusively pertain to overt acts such as saying the n-word or participating in a white supremacy protest; it also includes covert and subtle forms of prejudice, from microaggressions and supporting the police force in the United States to not using one’s privilege and platform to speak out on social injustices such as the killing of George Floyd.

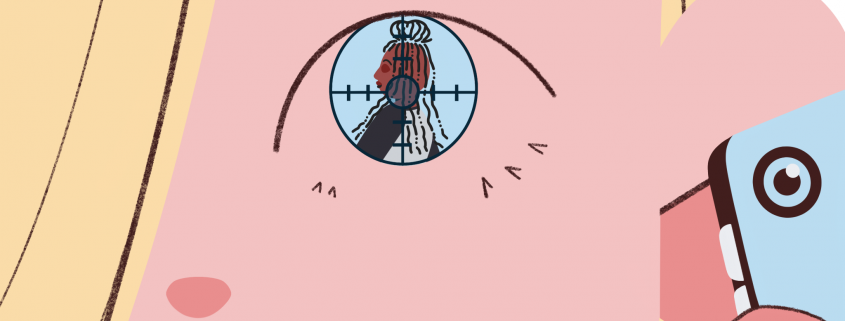

If one still denies that police violence is a “person problem” and not a race problem, I want to draw attention to another incident between a white woman and Black man, which occurred May 25 in Central Park. When Amy Cooper had her dog unleashed, against park policy, birdwatcher Chris Cooper (no relation) asked her to leash it. Chris Cooper then started filming the verbal dispute, where Amy Cooper claimed he was threatening her and called 911. “An African American man is threatening me,” she told them.

While making that phone call, Amy Cooper was fully aware of the implications of calling the police on a Black man. She endangered his life by feeding into the structural racism that killed George Floyd. Her actions reinforce the fact that police brutality is a systemic, embedded issue — and, even more disturbingly, that white people know this and are willing to exploit it for their benefit.

The paradigm of these killings reveals that justice must be approached systemically or no comprehensive change will ensue. All four officers present at the scene were fired and are now facing charges in George Floyd’s killing, yet this occurred following a viral video and national outrage. Peaceful protests demanding justice were met with tear gas, yet the white supremacists equipped with assault weapons at the Michigan State Capitol were met with silence. Colin Kaepernick sparked controversy by kneeling to peacefully protest systemic oppression, yet George Floyd was killed by the knee of a police officer.

We must elect officials who will advocate against institutionalized racism and work to reorganize historically discriminatory policies. We must instigate constructive conversations that function to educate each other and thwart overt and covert forms of white supremacy alike. We must act so that we do not need to demand justice for victims like George Floyd ever again.

Like Ng writes, “Sometimes we need to scorch everything to the ground, and start over.” As we work to subvert oppressive systems of power and ingrained racism, a form of this proposal seems apt.

Matthew Eck is a rising junior writing about culturally relevant social issues. His column, “The Eck’s Factor,” runs every other Wednesday.