Letter from the Editor: The inherently imperfect world of audience engagement journalism

I will not say this perfectly.

I will not say this perfectly.

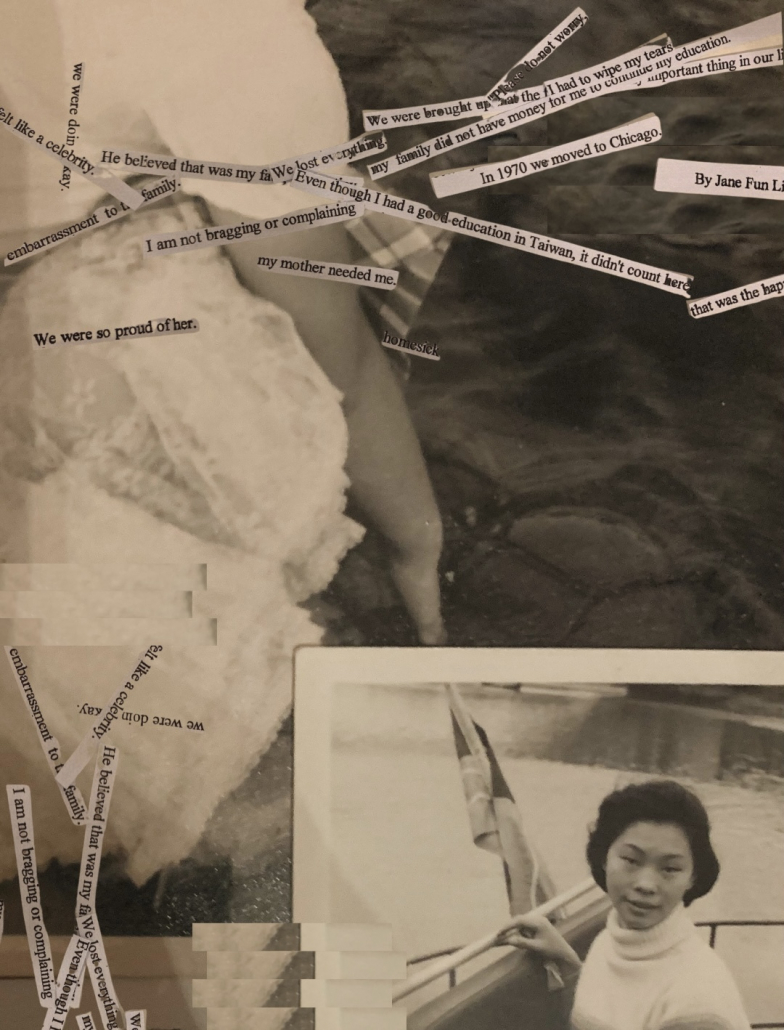

I will not say this perfectly, but if I do not say it at all, it will sit inside me. It will slowly pull me apart. And it will be passed on to my children the same way my mother’s story and her mother’s before her live — and sometimes tremble — within me now.

My name is Julia Lin, and I am the social media director for the Daily Trojan.

A lot of you might not even know this position exists, or you might think it’s not real journalism, or that all I do is post on Instagram.

But it’s a job I take seriously. It’s one that I think is important — connecting our generation, which barely reads the news, to the stories that shape our futures.

Last week, it felt like a heavy position to hold. I felt no desire to post stories on our Instagram. I felt exhausted every time I opened the app to see headlines or blanket posts that didn’t address the truth of our diasporic experiences shared on social media without thought or self-reflection. I felt guilty when the Daily Trojan had no articles to share that acknowledged the trauma many in our own newsroom were experiencing. I felt trapped by the knowledge that I have access to a platform, but wasn’t using it to share resources.

There are a million things to say. A million things on my mind. I’m thinking about what it feels like to be an Asian American woman. I’m thinking about learning to check behind me no matter where I am, and the way such targeted acts of violence on my own community only serve to substantiate those fears. I’m thinking about the deceptively dangerous rise of the Instagram infographic and the power of social media. And I’m thinking about the privilege I have to be an aspiring journalist and to be able to access things like USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism and the Daily Trojan, but also the ways these things have continued to fail me.

Last week, I watched the journalism industry that I aspire to be in do, frankly, a terrible job reporting on what had happened. I thought about writing to process or to call for action but let myself cry instead. I let myself be tired, frustrated. I let myself not have the words. But I also felt the relentless pressure I know many journalists feel when the speed of the news cycle means that allowing myself to process means that, by the time the pain subsides enough for coherent sentences to form, it’s already too late.

The news lets these stories come in waves, but the reality of these experiences is a constant feeling of trying to stay afloat.

I feel a deep responsibility every time these big moments of increased “awareness” happen. I feel as if I’m supposed to magically be able to solve all of these issues by figuring out just what to say or post for the paper. I find myself wondering if everyone will hate me if I don’t find something meaningful to share from the few stories we have about these issues. What does it mean to be an audience engagement editor? How can I engage you all in conversations that I am still learning how to have? I put a lot of pressure on myself to handle these things perfectly. The past few days, that pressure has left me completely unsure of what to do next.

Sometimes this job is fun Twitter threads and Instagram polls. Sometimes it feels empty, performative, hopeless.

Last week was, among many things, a reminder for me that these issues — of white supremacy, the myth of the model minority, of misogyny, hypersexualization and dehumanization — won’t be solved on social media.

This is not to excuse myself from actively reflecting on the stories we share, and it is certainly not to excuse our paper from the holes our coverage has had again and again. But it is to allow me to think deeper on where I fall within it all.

Social media is a unique and powerful platform, but it has allowed us to become dangerously complacent. It has made sharing an Instagram story a one-and-done box on some imaginary “activist checklist.”

Your Asian friends know what happened. We heard it from our mothers crying on the phone. We had it thrown at us in palatable Instagram stories. Spit in our face, and whispered towards our backs.

What we don’t know is what you’re doing to tangibly change the circumstances that leave us living in a constant state of fear that has become so second nature we sugarcoat and say we’re just anxious.

I’ll be honest. I’m hating on social media hard for someone who wants to be an audience journalist. For someone who shares these posts too. For someone who recognizes that sharing is a huge part of spreading news, especially these days when more and more people get their information from digital platforms. And sharing is great. Awareness is too.

But when sharing an Instagram post becomes an excuse not to do anything else, problems arise. And with USC students especially, I watch this happen again and again. I’ve watched hundreds of people sharing solidarity posts for communities of color on Instagram only to turn around and go to massive parties in the heart of South Central L.A. during the middle of a pandemic. I’ve had friends tweet and post and comment but not know how to have a real conversation about why last week’s news was so heavy for me. Social media allows us to pretend we are something we’re not. It allows us to make others believe, and in the process, it allows us to trick and excuse ourselves from doing the real work.

I want to bring myself back to the reasons I felt called to write today — the broader institution of journalism and audience engagement itself, and the ways the shortcomings of these fields are constantly reflected online and at USC.

This looks like the “fault lines” presentation students in Annenberg get every semester, which gives surface level information on diversity and inclusion in journalism, and it looks like the exhaustion students of color feel when we watch our white classmates walk away still not understanding how the language they use can harm.

It looks like all of the ways we are taught to write and interview and pitch that perpetuate the systems of implicit and explicit racism that are directly in line with the power dynamics that not only allowed but empowered last week’s act of violence and the following miscoverage to occur.

This looks like AP style being the supposed exemplary model of journalism, but the Associated Press reporting that maybe it wasn’t a hate crime just because the perpetrator himself said it wasn’t one.

This looks like being told not to use the word “spaces” when that is the only word I can find to describe the abstract place I desire simply to be seen when every other institution has failed me.

Maybe, for some, social media is that space. Maybe this intersection between the news and the internet is one that will always feel challenging to navigate. Maybe I will always feel like I am floating in the space between awareness and performing. Maybe as an Asian American, I am used to floating.

Maybe audience engagement means just being willing to ask you all what space you need. And how I can best create it.

Maybe to do well in this position I need to get over this fear of not getting it perfect. This fear of never being heard. Maybe this looks like forgiving myself, continuing to learn and unlearn, providing support when I can, and asking for support when I need.

Maybe you’ll stumble across this piece on social media. Maybe — hopefully — it will make you feel the tiniest bit seen.