I Reckon: I owe my soul to the Amazon Store

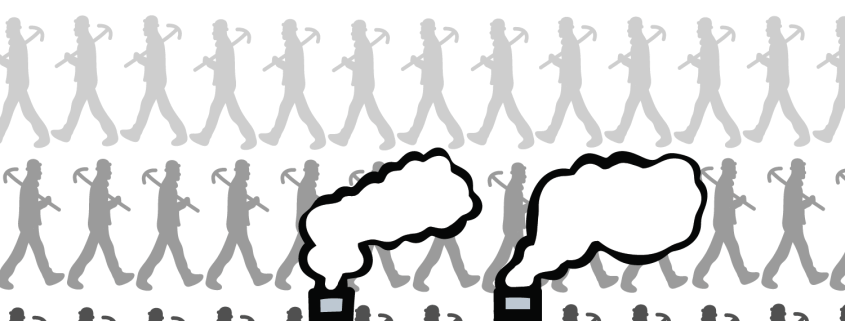

When it comes to labor practices, history is a great indicator of what works and what doesn’t work. We take a lot of things for granted nowadays, including practices in the workforce. We still have a ways to go until the working class experiences justice, but we owe shorter work days, generally safer working conditions and better benefits to the folks who came before us.

We are in a much better place now than decades ago because past laborers refused to stand by while employers subjected them to undignified conditions and starvation wages. A recent Bloomberg opinion article, however, promoted the benefits of Amazon company towns. The writer seems to have completely forgotten business-built towns’ horrible conditions.

While many may not know about company towns, we should be glad they aren’t as common anymore. Typically in rural and isolated areas, company towns center around large industries or factories that produce raw materials or products, such as coal or automobiles.

Company workers — and their families — usually live in company towns and go to nearby factories or plants for work. These towns may offer recreational activities in addition to housing, and it isn’t uncommon for a company town to pay their employees in scrip, or non-legal tender, for them to use exclusively in the towns’ stores.

Currently, Amazon doesn’t own any company towns, but it employs some of the same sleazy tactics and practices that made company towns reprehensible. First and foremost, company towns often don’t have the best working conditions. Amazon’s horrid workplace environment — including unreasonably high mandated hours, extremely short breaks and an injury rate three times the national average — are well documented. Therefore, it is doubtful Amazon would suddenly employ better workplace practices if it were to organize and run its own company town.

Additionally, the company’s sheer presence makes it an ever-expanding tenant. Amazon has a lot of influence whenever it occupies an office space or builds a fulfillment center because of the prospective positive economic impact. Recall the intense PR battle between states and local governments back in 2017 when Amazon looked to build another headquarters. If it means bringing jobs to their area, states and local governments contort themselves to appease the company while not paying any mind to the quasi-company town’s long-term effects on their communities.

The residents of Otay Mesa currently feel the effects of what could be an Amazon company town in the making. In this quiet, unbothered part of southern San Diego, Amazon plans to build a new distribution center, and resident advocates worry that Otay Mesa’s affordable housing plans will build housing in industrialized areas. A company-centered housing development might as well just be labeled a company town. In Otay Mesa’s case, however, the local government is doing most of the building.

Building housing and communities around industrialized companies — especially in a day and age when companies exploit cheaper labor — is short-sighted. If Amazon were to close its Otay Mesa facility, what would happen to the people who worked at the company and lived in the surrounding housing units? In West Virginia, a local union branch warned families they would probably have to sell their homes and relocate when a pharmaceutical plant closed and moved its operations to India and Australia. Companies can quickly pack up and move their operations, but middle and working-class families aren’t afforded that same kind of privilege.

We also shouldn’t forget about scrip: At least one Amazon facility rewarded their workers with “swag bucks,” which were only valid for purchasing Amazon products. While “swag bucks” are merely an incentive, Amazon blatantly attempts to cheat their workers out of real money through the use of non-legal tender, which makes them dependent on the company. How can Amazon workers possibly build wealth when part of their hard-earned money comes in the form of fake money?

The only thing stopping Amazon from creating full-fledged company towns is the expense of developing land, which is comparatively higher than the cost of leasing office space and facilities. One quick look at Amazon and its recent business decisions, combined with its history as an employer, doesn’t exactly paint the company as a benevolent employer. If Amazon starts to seriously consider building company towns in the near future, state and local governments ought to give the industry behemoth the cold shoulder.

Quynh Anh Nguyen is a sophomore writing about current political events as an Asian-American Southerner and California transplant. Her column, “I Reckon,” runs every other Tuesday.