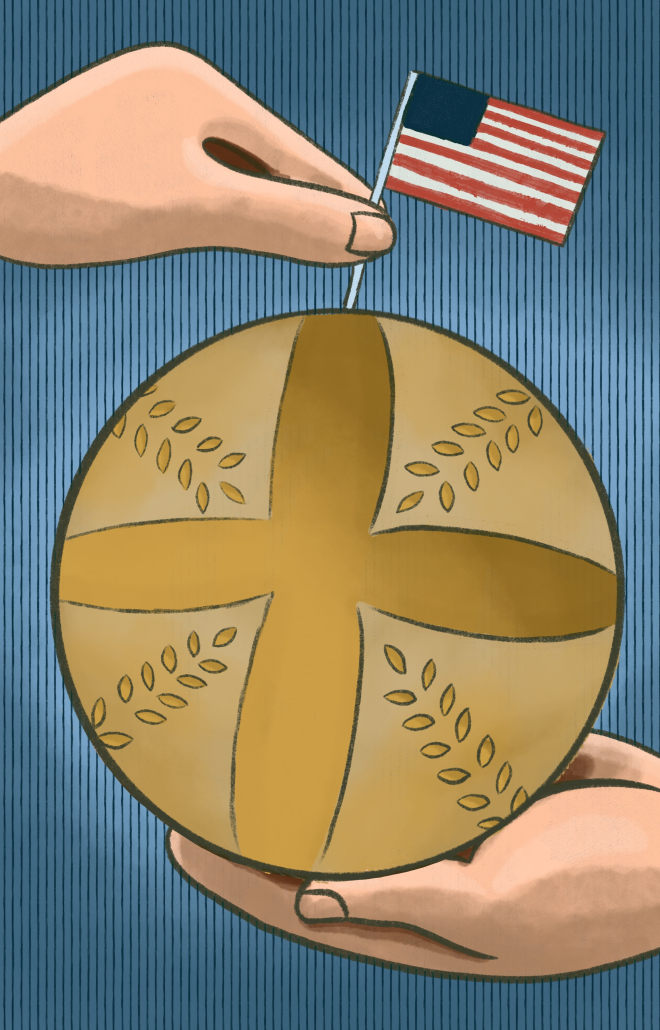

Good Taste: White people’s sourdough craze highlights colonization

June 16, 2020, 10:42 p.m. The moment I became a mother. Eleven months later, I remember the emotions that coursed through my veins the second I stirred together the rye flour and water that made me a mother to Doughby, my magnificent sourdough starter.

Like much of the internet, I spent 2020 fostering an obsession with naturally-leavened bread. As part of the sourdough community, I feel like one of the lucky few who discovered this special world of fermentation, privy to the pleasure and privilege of slicing into freshly baked sourdough loaves.

It took me months to realize fermenting dough was not the novelty I believed it was. I’ve been watching my mother make dosa batter for longer than I can remember. Soaked rice spends days developing a pungent sour flavor, eventually transforming into light, crispy crepes filled with spiced potatoes. The process might vary with sourdough bread, but my mother has performed the ancient art of fermentation for years.

This chemical process is all around us, playing an integral role in everything from Korean kimchi to Nigerian cassava. Despite fermentation’s rich history and multicultural span, Western practices predominantly informed the pandemic’s fermentation craze. Since sourdough’s pandemic-induced internet fame reinvigorated this age-old practice, we’ve ignored its ties to Black and brown communities in favor of viral crumb shots.

For many bakers, sourdough transitioned from an Instagram trend to a business model. Beyond crumb shots and scoring patterns, bakers with thousands of Instagram followers can seek out brand deals, start their own podcasts and sell their own sourdough recipe books.

For instance, Kristen Dennis, known as @foolproofbaking on Instagram, founded a company that sells products for home sourdough bakers. Similarly, many consider Maurizio Leo, creator of The Perfect Loaf blog, to be one of the most informed sourdough bakers, and his blog inspired thousands of people to begin their own fermentation journey. Through his social media presence, he landed a job as the resident baker for Food52, a well-known culinary magazine.

The sourdough community’s home-baker-to-wealthy-influencer pipeline is no different from the average person’s transformation into an Instagram personality. Despite appealing to different crowds, well-known sourdough authorities and influencers both leverage their following to earn money.

Although fermentation holds a rich history in communities of color, most profiting sourdough bakers are white. The most popular sourdough authorities on Instagram are Dennis, Matthew Duffy, Leo, Bryan Ford, Mike from Rosehill Sourdough, Gareth from Memoirs of a Baker and Hannah from Blondie and Rye. Of the “Big Seven,” six are white.

Fermentation was born in Black and brown communities, from North African yogurt to Indian dhokla. Historians date fermentation back to Ancient China in 7,000 B.C. Others speculate dairy fermentation started as early as 10,000 B.C. in Northern Africa. Although we do not exactly know when it was invented, we do know bread fermentation was first recorded in Egypt and later spread to Greece and France. In the Western world, it is this Egyptian-inspired naturally leavened bread that has since evolved into the modern day sourdough bread.

However, the more fame the practice receives, the fewer fermenters of color emerge as authorities in the space. As bakers such as Dennis and Leo turn baking sourdough bread into a financially profitable business, they forget this practice began in communities of color — a practice white bakers now leverage as a financial scheme.

Fermentation is one of the many instances in which white people have taken work from communities of color and rebranded it. For example, following the murder of George Floyd in May 2020 and the reemergence of the Black Lives Matter movement, people formed book clubs with the intention of reading anti-racism literature.

Anti-racism literature topped the non-fiction charts week after week, with one book repeatedly at the #1 spot: “White Fragility” by Robin DiAngelo, a white woman who explains race from the lens of someone with race privilege. She distills what she has been taught by people of color, but many argue she delivers the knowledge in a way that talks down to Black people.

Countless Black authors published books about anti-racism, but many Americans do not appreciate their work because they are more comfortable learning about race from the perspective of someone who has never experienced racism. Devaluing books written by authors of color reinforces the ideology that white work is more respectable and prestigious.

It may seem superfluous to critically think about social media bakers’ races, but sourdough culture is a microcosm of white people’s colonization of Black and brown work. The sourdough community reflects our society’s acceptance of white professionals profiting off people of color’s work.

Mothering Doughby has connected me to a virtual community of fermenters, but as the practice becomes more popular, voices of color are fighting for a place in the conversation they started. The prevalence of white authorities in fermentation is a reminder of the work needed to dismantle the colonization of Black and brown spaces.

There is a world in which equality and justice are not just ideas but a way of life. By amplifying Black and brown voices, we have the power to create such a world, starting both inside and outside the fermentation community.

Reena Somani is a senior writing about food and its social implications. Her column, “Good Taste,” usually runs every other Thursday.