FINANCE: $23 billion state budget deficit could hurt colleges

Back in May, legislators in Sacramento were mulling over how to allocate California’s $97 billion budget surplus. The surplus’ size was so large that Governor Gavin Newsom, during the budget announcement, declared it as one that “no other state in American history has ever experienced.”

Less than a year later, the state is facing a deficit of $22.5 billion and, with it, the prospect of scraping through the barrel to continue funding its government programs. As the state government looks to shore up its balance sheet, higher-education institutions across California are likely to be hurt by funding cuts, creating a “huge problem,” said Christian Grose, a professor of political science and public policy at USC.

“The higher public education system is about to take a big hit, and the governor and the state [are] going to have to figure out something to do about that,” Grose said.

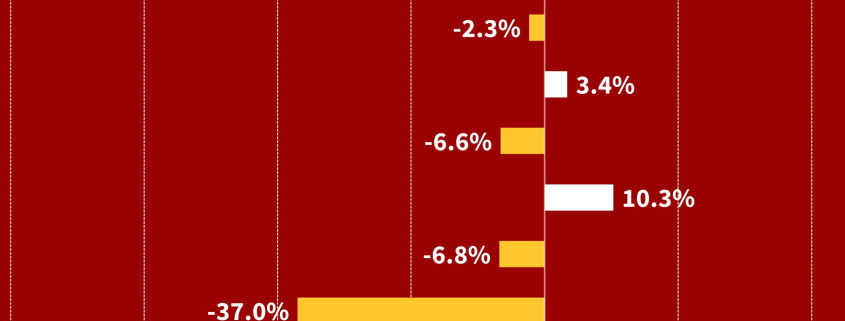

In a budget proposal earlier this month for the upcoming 2023-24 fiscal year, Newsom promised to keep up his pledge of increasing base funding to succeeding universities in the University of California and California State University systems by 5% year-on-year, despite the deficit. In the same breath, the governor also proposed a drop in overall funding for higher education by 2.1%, to $40 billion — the first decrease in 10 years. The reduction includes the delay of billion-dollar projects revolving around the creation of housing for low-income students.

Although USC itself is relatively “insulated” from the direct effect of the state’s budgetary concerns because of its private school nature, Grose said, the repercussions extend to current undergraduate students headed to graduate school in-state and to those aiming to transfer into the University.

Just weeks after the University of California system’s academic workers heralded historic wage gains in new labor contracts signed in December, California’s deficit has sparked further questions about UC’s ability to rely on state funds to help cover the costs. They are now scrambling to find ways of creating income to pay for them and are considering cutbacks in graduate student admissions.

“One of the benefits of California is that it has such a good education system, from community colleges to the UCs,” Grose said. “You don’t have to be affiliated with those institutions to see the economic benefits that come from that — and they are all facing some pretty serious budget problems.”

Funding would also be delayed for capital projects at UC schools that include the $200 million construction of an Institute for Immunology and Immunotherapy at UCLA, $83 million to support a clean energy project at UC Berkeley and another $83 million for campus expansion projects at UC Riverside and UC Merced.

Delays to housing projects are causing concern among some legislators in the state’s capacity to tackle housing insecurity and the subsequent declines in enrollment across community colleges. Community colleges have lost 18% of their enrollment since the start of the pandemic; USC especially relies on community colleges for about 47% of its transfer intake.

The deficit that has developed since the announcement of last year’s record surplus means that the state government’s spending has far exceeded its ability to bring cash in through tax. It’s a reversal of economic fortune that Frank Zerunyan, professor of the practice of governance, said was “remarkable” — a “perfect storm” that stems from the previous year’s “irresponsible” spending.

“California lined up to dole out a bunch of cash to people [who] certainly needed it, and people that did not necessarily need it,” Zerunyan said. “When you govern, every cause is a great cause … California, with that budget surplus, was not able to say ‘no’ to a bunch of projects. The spending went crazy.”

California’s residents received financial assistance through stimuli known as the Middle Class Tax Refund in 2022. Lawmakers included the aid as a bill in last year’s budget as the state took advantage of its surplus, with direct payments of $350 to $1,050 being distributed to approximately 31 million Californians — more than three-quarters of the state’s residents. The program has cost the state more than $9 billion so far.

Falling tax revenues have also been attributed by economists to spiraling inflation and a weakening stock market. To combat inflation, the Federal Reserve has consistently hiked interest rates since March 2022, in turn slowing economic growth. Big Tech firms, including Google and Amazon, have each cut tens of thousands of jobs, and the lethargy in growth has extended to other sectors, such as banking.

This has caused many wealthy individuals to make much less money through capital gains on their stock investments. In California, where the top 1% of earners account for nearly half of all the state’s income taxes due to its strongly progressive tax system, the downward effects have been huge for its revenues.

“As the downturn has spread to the technology and finance industries, that has a direct impact on the stock market, and the fact that California has such a steeply progressive income tax system creates both an economic challenge and a political challenge,” said Dan Schnur, an adjunct professor of politics, communication and leadership.

While Newsom has proposed some cuts to schools, he has mostly committed to keeping them to a minimum. His funding cuts to the fight against climate change, transportation, housing and workforce development programs are much larger.

“To his credit, one thing Newsom has done is he’s really strong-armed the legislature over these years of budget surpluses into building a budget reserve,” Schnur said. “That’s going to help protect against the worst cuts, or against the most onerous tax increases because they’ll have reserves to draw from.”

The worry for Schnur, as well as for legislators, is that continued spending, combined with uncertainty over the future state of the country’s economy and interest rates, could create a recession that would exacerbate such problems for many of the state’s sectors.

“The biggest concern in Sacramento now is not this year’s deficit, that, while difficult, will be manageable,” Schnur said. “Their concern is if an economic downturn continues in the next year, that’s where the much more painful decisions are going to come into play.”