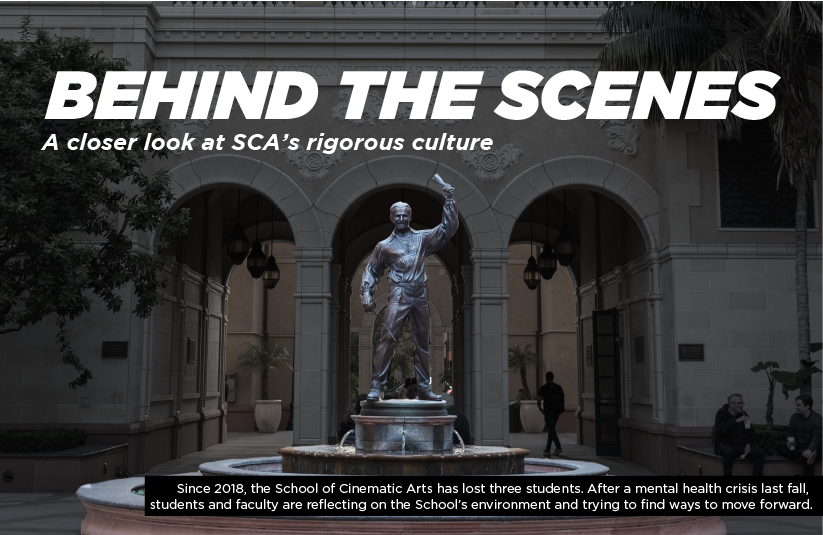

Behind the Scenes: A closer look at SCA’s rigorous culture

As some universities release their plans for the fall amid the coronavirus pandemic, students from the School of Cinematic Arts took to social media to circulate a petition April 21 calling for the School to pause production classes.

The petition asked for SCA Dean Elizabeth Daley and Division of Film and Television Production chair Mike Fink to pause the production track should USC decide to continue online in the fall until in-person classes can resume. With over 750 signatures at time of publication, the petition notes that these students will consider taking a leave of absence for the semester if this change fails to be implemented or considered.

But before the coronavirus disrupted the USC community, there was another public health crisis on campus — and more specifically at SCA.

Early November, Chief Health Officer Dr. Sarah Van Orman confirmed to the Daily Trojan that nine students died over the Fall 2019 semester. Two were SCA seniors: John Moore, who was majoring in cinematic arts, film and television production, and John Lynch, who was majoring in screenwriting. Both died from accidental overdoses.

On April 27, Van Orman confirmed to the Daily Trojan that three additional online students died over the Spring 2020 semester. According to Van Orman, these students were older than the college student demographic, and the causes of death were different from those in the fall, which she said saw a “cluster effect” in the deaths.

Moore’s and Lynch’s deaths were not isolated incidents at the School. In April 2018, SCA was rocked by the death of screenwriting student Mckenna Martin, who died by suicide. The SCA community — along with the entire USC community — was left “shell-shocked,” said Leo Allanach, a senior majoring in cinematic arts, film and television production.

In response to the deaths last semester, SCA partnered with USC Student Health to integrate an expansion of Let’s Talk, a drop-in program for students to seek guidance from mental health counselors in an informal discussion setting.

According to Dr. Kelly Greco, assistant director of outreach and prevention services at Student Health, the expansion has transitioned to one-on-one counseling with two full-time clinicians at SCA this semester. Amid the pandemic, counseling has continued online.

Aside from counseling, director of student services Marcus Anderson among other faculty and staff has held forums and meetings with students to discuss their concerns. Though most have been emotionally driven, Anderson said in December they started to brainstorm pragmatic changes that they want to make at SCA.

“Conversations now are very practical in nature of what do we need? How can we do that? What is the most effective way to implement change, and how can we do things quickly?” Anderson said. “And then what do we need to do long term? Ultimately, we’re running a long-term approach here because we want to make sure that SCA is a place where students, faculty and staff, everyone can thrive.”

Despite these efforts, Allanach said the deaths are proof of a systemic issue of failing to address the mental health of students at the School.

“Until we’re making more of a student movement and student stance, it is so easy for them to say things behind closed doors and agree to certain things and play up these niceties and not do anything,” Allanach said.

The culture of SCA production

For Allanach, and for many of his classmates, the fall semester of junior year was his most difficult.

Allanach was taking “Intermediate Production,” a required mid-curriculum course otherwise known as “310” among production students. Notorious for being mentally and emotionally taxing, 310 puts students in trios to produce three films in 15 weeks, rotating them between filmmaking roles so that each can develop skills in producing, shooting, writing and directing their own films.

The course tested Allanach’s limits. While 310 is a six-unit course, translating to six hours of instruction per week, Allanach found himself in class for 12 hours per week and spending his weekends working on the films. Even though he came into the class with the expectation that he would have to take better care of himself during the course, he said it was nearly impossible to prioritize his well-being.

“It’s tough,” Allanach said. “310 was absolutely the hardest semester for me, and it’s weird seeing almost the repercussions of that and the fallout of that a year later.”

Poor mental health among students is tightly woven into the culture at SCA, but such a culture has been perpetuated by the School itself, said Oona Wuolijoki, a senior majoring in cinematic arts, film and television production. When Wuolijoki first came to SCA in 2018, she said Daley didn’t shy away from stressing the rigor of the School when she welcomed new students.

Daley said in an interview with the Daily Trojan that through its curriculum, SCA aims to provide students with a realistic view of the entertainment industry.

“It is a rigorous curriculum,” Daley said. “This is a professional school, and the last thing on Earth we ever want to do is not to give students the education that they need in order to be successful when they leave.”

According to professor Bill Yahraus, who has been the 310 course coordinator for more than 20 years, the class is not a weeder course. The level of stress that comes with the class depends on the student and how much weight they place on it within their overall curriculum, he said.

“This is not that difficult of a course, and you have tons and tons of support,” Yahraus said. “I really try to say to everybody, these [projects] are exercises, so … it’s not designed to be that kind of a course. That doesn’t mean that some students take it very seriously.”

According to Yahraus, amid the pandemic, some work for the second films in 310 went online and has yet to be completed. Students will finish their third films next semester in “The Production and Post-Production Assistant” course, another required course.

Other students such as Dylan Mondschein, a senior majoring in cinematic arts, film and television production, found that while 310 was tough due to its tight deadlines, she expected its level of rigor. She added that her friends in the program cautioned that she’d need to give up her social life for the course.

“That was a really daunting thing for me,” Mondschein said. “But the amount I learned in that one semester is mind-boggling. I grew more in that semester than I have in any other semester in college, at least creatively.”

Moore, who died in October 2019, was in Allanach’s group but ultimately decided to take a leave of absence for health reasons before they started their second film.

Allanach recalls one weekend shoot about two weeks before Moore’s leave of absence where Moore took frequent trips to the bathroom because he was not feeling well. Allanach asked for Moore to leave and get some rest, reassuring him that he would not get in trouble, but Moore, who was the cinematographer, decided to stay, since class rules prohibit students other than the cinematographer from touching the camera. When Moore later explained the circumstances to the professors, they told the group they should have stopped shooting until Moore was physically able.

“They kind of push this thing as you have to follow every rule, but then also the most important thing is that it gets made no matter what,” Allanach said, adding that the short deadline frustrated him. “It’s like, OK, we can either have one or the other. We can either have it presented to you, and you can ignore the process, or you can emphasize the process and recognize that the finished product will not be what you want it to be.”

While the group’s professors made arrangements for them to work without Moore by letting them complete only one more film, the two were only allowed to work on their next film while other trios were completing their third films. Additionally, Allanach and his partner were instructed to split Moore’s responsibilities rather than find someone else to help. To help lessen the workload, Allanach brought a friend in to unofficially step in as the producer, but they got into trouble because the faculty wanted the two to complete the film by themselves.

“It was this whole mess of like, I don’t know what you want from us,” he said. “We’re trying to do the best that we can in the circumstances that were given.”

Dave O’Brien, Allanach’s producing professor for 310, declined an interview with the Daily Trojan, but indicated that he and other 310 faculty had been in regular contact with the students to make arrangements that would guide them toward an agreeable outcome.

There is no way to completely buffer against the realities of a trio losing one of its members, but O’Brien told the Daily Trojan that he believes the faculty responded appropriately.

“There’s just a big difference in what the faculty see and what the students see even if they try their best to communicate, unless they’re really making an effort to be empathetic of the different circumstances,” Allanach said.

After speaking at an SCA forum in 2018 regarding the school’s structural issues, Allanach said he was pulled into Anderson’s office for a meeting. There, he was advised to consider dropping out of his major.

Anderson said SCA would never recommend that a student drop a program, but if a student is not happy with their major, he talks with them about whether or not they want to continue pursuing the field. With Anderson’s help, the student can then look into other programs within and outside of SCA they may be interested in transferring into, he said.

“Our primary concern is the mental health of our students,” Anderson said. “So it’s not a recommendation that they transfer over, it’s more of a sit-down discussion to make sure that the student is comfortable with the program and actually wants to continue it.”

But for some students these forums and talks are simply not enough. Mondschein said SCA should provide more of a nurturing environment where students can feel safe having important conversations with their teachers and build deep relationships with them.

“People are really afraid to criticize anything because these are people who hold a lot of power, who could change our lives or careers, and so this is not an environment in which people feel necessarily safe to discuss the things that are plaguing them,” Mondschein said. “And I think that’s its biggest downfall.”

The issue of drug use

When it was confirmed by the Los Angeles County Medical Examiner-Coroner that both Moore and Lynch died of accidental overdoses, Nancy Forner, head of the editing track in the production division, believed it was necessary to discuss with her students the issue of using drugs, namely fentanyl, of which traces were found in Moore’s blood.

“I stopped and took time and I explained to them … there is a drug out there that you might not know about,” Forner said. “And I explained to them the dangers of that … I wanted them to know because not everyone knows these things.”

To Wuolijoki, drug use on campus has been more stigmatized than mental health issues, noting that it is “absolutely insane” that the discussion surrounding addiction has been discussed entirely separately from mental health. She explains that they are “intimately linked.”

Wuolijoki said while most professors have taken drug issues at SCA seriously, she said that during a memorial for Lynch, Daley advised people to not do drugs, which Wuolijoki likened to an attempt of former First Lady Nancy Reagan’s “Just Say No” campaign in the 1980s.

“We’re talking about addiction,” she said. “That’s not fixed by some sort of Nancy Reagan shit. Sorry.”

According to Mondschein, self-medication with drugs and alcohol is normal behavior for some students. During her time at SCA, she said she observed young artists often aspiring to embody the personas of the successful artists that came before them, but these artists are often people who have dealt with addiction and mental health issues.

When Mondschein first got to college, she decided to take a break from going to therapy, as she had done in high school. But as her mental health steadily declined her sophomore year, Mondschein sought help from the Engemann Student Health Center, which referred her to an external psychiatrist who she said prescribed her medication that caused her to develop suicidal thoughts and a poor appetite.

As a result, Mondschein found herself drinking frequently. That year, Mondschein dealt with substance abuse and developed a dependent relationship with alcohol. But when Martin passed away in April 2018, Mondschein, who was close with her, said her death was a wakeup call. She decided to go back to therapy.

“That was something that only therapy could really change for me, talking about my problems, working through them,” Mondschein said. “[Self-medication is] a valid way of protecting yourself, it’s not like coming from a place of, ‘I want to get addicted to drugs.’ It’s like ‘No, I want to take care of myself, and I don’t know how.’”

Mondschein said there needs to be more conversation surrounding drug and alcohol use — not just in the context of addiction, but rather as a mental health issue, since it is often comorbid with depression, anxiety and other mental health illnesses.

Anderson said that while there has been conversation around drug use among SCA faculty, there needs to be more of a dialogue throughout the University, since it concerns all staff.

“It’s kind of a delicate balance though because conversations around drugs can very quickly and easily steer into lecturing,” he said. “And that is not the type of conversation that needs to be occurring, and so it’s more of engaging in those individual dialogues with students and having discussions about it.”

Since Martin’s death, Mondschein has served on the board of directors for Mckenna’s Grace, a nonprofit organization in honor of Martin that aims to eliminate suicide on college campuses. The nonprofit is currently developing the Grace App, which will provide students a platform to “both give and receive support and affirmations, as well as access mental health resources,” according to its website.

“By being associated with Mckenna’s Grace, I think it also just kind of inspired me to be very open about my own issues and very candid about mental health,” Mondschein said.

Moving forward

As a 310 professor, Forner said faculty members have well discussed mental health issues, with every meeting dedicated to brainstorming ways to make improvements to SCA’s curriculum while maintaining its rigor. Forner said it’s a difficult balance to achieve.

In Spring 2019, the 310 faculty implemented a change in the way they assign “dailies,” or raw footage students gathered from the prior weekend of shooting. Instead of having students watch each other’s dailies frequently, faculty now requires only the trio whose dailies are to be shown to go to class and get feedback. With this change, Forner said other students can take the extra time to catch up on sleep or do other work.

Forner said she has been like a “mother hawk” to her students, making sure to check in with them frequently. In her years teaching 310, she has had a handful of students who have come to her to talk about their stress and mental health. Forner said she would walk students over to Engemann to meet with counselors and then check in every night to make sure they were eating and getting enough rest. In some cases, students opted to take a leave of absence as Moore did.

“We do this little thing until they’re past the hurdle, and I’ve suggested to other teachers, and other teachers do it — I know they do, I’m not the only one,” Forner said. “The faculty really cares. I mean, we think of these students as our children, and I know that sounds corny … but it’s true.”

Looking ahead, Daley said the School is working with Campus Wellbeing and Education to repurpose the “Reality Starts Here” course every SCA freshman takes to get introduced to the School’s resources into a “life skills” course focused on health and well-being, spearheaded by Anderson and Interim Assistant Dean of Diversity and Inclusion Evan Hughes.

Additionally, the School will offer a new required course on collaboration for production MFA students titled “Collaboration and Creativity,” given the amount of teamwork that is required in SCA and beyond. These courses, which will be offered Fall 2020, will help students get a more realistic and holistic view of the entertainment industry, Daley said.

“You’ll never make a film or a game or a television show not on a team, so I think we want to get some deeper understanding of what it is people really want to do and what their skillset is,” Daley said.

Additionally, Anderson helped integrate SCA Chats, biweekly sessions for students to drop in and discuss concerns. The sessions are held at different times and days of the week to accommodate students’ schedules, and SCA rotates who is leading the sessions in case some students feel more comfortable speaking to some faculty more than others, Anderson said. Due to coronavirus-related restrictions, Anderson said the School is holding SCA Chats via Zoom.

Students have also been doing their part to bring more attention to the issues they see at SCA. After Lynch’s death in November, a production major published a letter in the Daily Trojan detailing her experiences — and frustration — during her time at the School.

“We may be hurting right now, but this is an opportunity to make meaningful changes to a program that has lost too many students,” Alyssa Callahan, who graduated in December, wrote. “Cultivating a more supportive culture where students are able to make mistakes and able to step back when necessary is what so many students not only want, but need — and we need it right now.”

That same month, Wuolijoki and a few other students surveyed production students on their mental health. With the responses, Wuolijoki said they created a list of changes they want to see at SCA for Daley, including hiring full-time counselors on campus.

But due to the pandemic, Wuolijoki said the momentum they had achieved seems to have diminished. With graduation in a few weeks, she said she is afraid that future classes are not going to be as proactive with demanding change because they are more removed from the deaths.

However, students like Lauren Rothman, a junior majoring in cinematic arts, film and television production, still plan on further mobilizing the community. For her “Production III, Documentary” course this fall, Rothman is directing “Life on the Line,” a documentary investigating the student deaths at SCA. Although the coronavirus has brought some uncertainty to how production will move forward, Rothman said she and her crew are still motivated.

“We all had this sense of, ‘We can’t just let things move on after this,’” Rothman said. “The second things shifted [due to the coronavirus] … we all kind of admitted that yeah, we’ve lost focus, and I think that kind of was the driving force that everybody needed to ramp it up and come at it even stronger than before.”