At USC, not all units have same weight

The number 128 is rather unadorned. It does not have the luxury of ending in a 5 or 0, and its three digits don’t form a clever pattern such as lucky No. 111. Nonetheless, at USC, it marks the end of a fantastic four-year journey. Once a student piles up four years’ worth of credits, he can leave USC as a proud graduate of one of the most prestigious institutions in the country.

But what determines how many units a class is given?

Essentially, classes are assigned a number of units based on what the faculty calls “contact hours” or class time. In order for a course to award its students four units, it must meet a minimum three hours a week.

There are, however, certain courses offered at USC where the units do not reflect the work required of students.

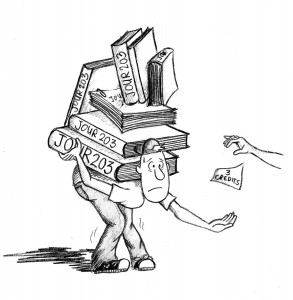

Newswriting: Print (JOUR 202) and Newswriting: Broadcast (JOUR 203), for example, are three-unit courses that meet two hours and 40 minutes a week. Just 20 minutes short of the four-unit mark, these two courses prove to be quite challenging to students — especially considering the fact that the courses require students to hold an internship during each semester.

As many Annenberg students grumble about this injustice, Patricia Dean, the associate director of the School of Journalism, argues that courses in Annenberg will inherently be difficult because they require students to acquire complex technological skills. From scrupulously editing camera footage to putting together stories on deadline, journalism students are expected to be accurate, thorough and fast.

Journalism students, whether or not they know it, sign up for a tough four years. But what about the students with other majors who want to take a journalism course to fulfill a general education requirement or simply rack up some units? They register for two-unit courses expecting an informative but laid-back experience — and often find anything but.

Imre Meszaros, the associate director of the School of Communication, said the aptitude of a given student, not units, often dictates whether the class will be difficult or not; therefore, it is “impossible to achieve exact equivalence across the classes.”

Admittedly, Meszaros has a point: Some students are smarter than others, and it is inevitable that some students will find certain two-unit classes painless and others will not.

But is student variance responsible for the discrepancy between work and units? Perhaps, but the amount of freedom professors enjoy ensures that no two classes are the same.

Unit numbers and even course numbers are almost worthless when one tries to gauge how tough a class will be. Meszaros said faculty can choose how they teach — whether that means having students read four books and write eight papers or requiring only one book and one paper for the same amount of units. Unless the class policy becomes so merciless or so gracious that the university sees the need to intervene, professors do as they please with little surveillance.

Because a class’ difficulty greatly depends on the professor’s style, students usually do not know what they are getting themselves into. This university-wide faculty freedom places serious doubt as to whether units hold any informative value at all.

In this respect, college academia is similar to high school, where the only way to get the inside story about a class is to ask its survivors. In high school, however, there were only two or three teachers who taught the same course. In college, numerous professors teach the same course and the chances that a friend had the same professor are much smaller. To make matters worse, a lot of professors don’t post their syllabi online, so course requirements are often hidden from public view.

So in the end, when faced with registration, students are without the resources they need to make educated decisions regarding what courses to take. Unit labels are unreliable, an updated syllabus is usually not accessible and there is too much inconsistency between professors in the same field. No wonder registration is such a stressful and uncertain time.

With all of these confounding factors, a course’s true difficulty is clouded until the first day of classes. Still, one thing is for sure: Not all units are created equal.

Conrad Wilton is a sophomore majoring in broadcast journalism.

I couldn’t agree more with you lawl. As an engineer, I have more than twice the hours of class per week as some of my friends who somehow get credit for the same number of units. Additionally, many senior year engineering classes are only 2 units, but I guarantee that those classes require more work than these journalism classes that people are complaining about only getting 3 units for.

I’m glad to see the Daily Trojan has started adding some articles for comic effect though!

journalism isn’t the only major with difficult 2 or 3 unit classes . ever heard of oh pretty much ALL of the engineering majors? quit complaining about your classes, ya sophomore!