Bureaucracy of college enrollment hurts students

Academic advisers across the country have become acutely aware of a phenomenon they are calling the “Summer Melt.” An increasing number of high schoolers are graduating with the intention of entering college the following fall but end up never completing the transition. More often than not, students either decide to stay home and work due to financial difficulty or do not have the time or expertise required to navigate the bureaucracy of college enrollment. We live in a time when America likes to think it has become more progressive on social issues because education reform has gained political momentum. This phenomenon, however, is a reminder that financial and bureaucratic barriers to college continue to significantly hinder low-income students from accessing higher education.

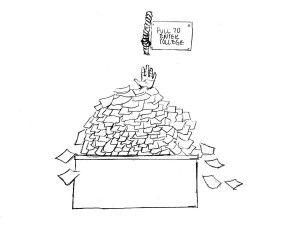

Between graduation and the first day on a college campus, there are many forms to complete, financial aid intricacies to work out and deadlines to meet. For low-income students or students responsible for their own livelihood, this obstacle course adds to a long list of hindrances. Students with college-educated parents often have an advantage in navigating bureaucracy that first-generation college students do not.

Recently, a national outreach effort has cropped up in an effort to give these students extra advisement and provide them with services like text message reminders for deadlines. Among the nonprofits that orchestrate these services is the Southern California College Advising Corps, which is run by USC. The fact that these students are not only noticed, but also helped is undoubtedly a positive thing, but the situation still calls for a long-term solution for how colleges communicate with incoming students.

One of the primary reasons that college bureaucracy can be so overwhelming and redundant can be attributed to privacy concerns. Much of the information colleges ask for — personal, social and financial — is sensitive and needs to be protected. Not to mention, the huge paradox with financial aid services, considering that low-income students who require more financial aid are less likely to have the expertise to navigate the system.

Ideally, the matriculation process would address issues of accessibility and navigability. Online platforms could certainly be given more user-friendly interfaces, and financial forms could be simplified or condensed to eliminate redundancies.

On a more general note, this trend also denotes a sentiment among students today that higher education is less of an investment in the future than a privilege for those who don’t have immediate financial concerns.

The most important thing to remember about the “Summer Melt” is that low-income students are by no means any less capable of completing college paperwork and getting themselves there. Rather, the headache of figuring it all out might lead them to think that entering the workforce right away has more tangible and readily available benefits. This has to do with how many might not see what they would learn in college to be applicable to the real world. For those who grew up during the 2001 and 2008 recessions, it wouldn’t be unreasonable to prefer starting out at a minimum wage job as opposed to entering a minimum wage job four years later with the added burden of college debt accruing interest at increasingly deplorable rates.

In the end, not only does higher education need to become less bureaucratic and more financially accessible, but education in general must also become a system students can believe in.