Government forms limit mixed race people

According to The New York Times, the current generation of college students is the largest group of mixed race people in America so far. The number of individuals who identified as mixed race is at 9 million. Increasingly more Americans find themselves in a gray area when it comes to defining their races. You might have heard of “Hapas” — people of partially Asian/Pacific Islander ancestry — or “Blasians,” people of mixed black and Asian ancestry. Though these types of self-identification are becoming more common in everyday language, a conflict arises when the standard “Check the box” race forms can’t properly identify a growing population of Americans. Most people do not cleanly fit into the four standard racial categories of black, white, American Indian or Pacific Islander.

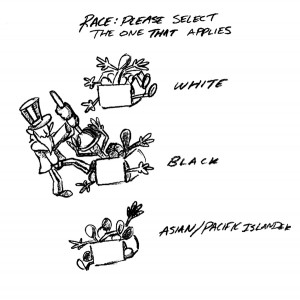

The problem with racial identification lies in faulty methods of collecting data about such groups. Questions of race in the United States have always been a particularly sensitive topic. With its peculiar mix of European colonists, American Indians and Spanish and French explorers, the U.S. has always struggled with race relations. In an effort to better resolve and address race questions in the modern era, the federal Office of Management and Budget has issued Directive No. 15. According to the official White House website, this directive “requires compilation of data for four racial categories (White, Black, American Indian or Alaskan Native, and Asian or Pacific Islander), and an ethnic category to indicate Hispanic origin, or not of Hispanic origin.” And here is the problem: A person is now forced to identify him or herself as one of only four races even though changing demographics show that there are more possibilities.

The idea that a person’s race is easily classifiable is flawed. For instance, the recent beating of Prabhjot Singh, a professor at Columbia University, shows the problems that arise from an ill-informed populace. According to the New York Daily News, Singh, who is an Indian-American Sikh, was mistaken for being Muslim due to his turban and beard. He stated that the thugs who broke his jaw “acted out of ignorance.” Clearly, a couple of boxes on a form are not responsible for racism in the United States. But race questions with such limited answers are a tangible manifestation of a failure to recognize and validate America’s growing diversity.

As an Indian-American, Singh doesn’t fit into any of the four most common answers to demographic questions. He’s certainly not white, black or American Indian. He might be considered Asian for the purposes of the geography, but in common language, “Asian” usually denotes a person of East Asian heritage.

The question is even more complicated when one considers that in the United Kingdom, an “Asian person” is one from South Asia or the Middle East, and East Asians are usually called “Oriental,” a term that is no longer in polite usage in the U.S. Even if Singh were Middle-Eastern, he runs into the same issue. Middle-Eastern Americans might not be considered “white” by most people. Yet, according to federal guidelines, people of Middle-Eastern descent are in fact “white.” But why? Undoubtedly, Middle Eastern Americans are not “white” because of their culture, skin color or religion, though they might share some of these aspects with other “white” Americans. For the most part, “white” seems a dreadfully inadequate term to describe someone from the Middle East, North Africa or Eastern Europe.

It’s important to note that in recent years, federal agencies have taken more proactive steps in identifying Americans of different racial backgrounds. Their approach, however, leaves much to be desired. According to the official Census Bureau website, the last two censuses have included more detailed options to identify a respondent’s race. The standard categories of white, black and American Indian are included, but there are further options to classify what kind of “Asian” a respondent is. These options include Asian Indian, Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Vietnamese, among others. Yet, what of Middle Eastern Americans? As of the 2010 U.S. Census, the same options exist for Asian identification, leaving some individuals to again identify as “white,” though a write-in category does exist. People from African or European countries are similarly left in the dark about how the U.S. government classifies them. Do the terms “black,” “African American” or “white” really explain their identities?

This lack of identification exacerbates the problem of racism and a lack of cultural knowledge. Perhaps an infamous Mean Girls quote best explains the situation. As Karen Smith asked, “If you’re from Africa, why are you white?” Sadly, with current controversies surrounding racism and racial identification in the U.S., it seems unfair to blame Karen for her lack of knowledge.

Though it would be a ludicrous to attempt to list every possible race, a simple addition of “Middle Eastern,” for example, does not seem an unfair request. Though such racial classifications may not seem important, they permeate many aspects of adult life. From college applications and the complicated questions of affirmative action, to the Department of Labor’s requirement that employers collect demographic data, it’s clear that race is an issue in America. It would be nice if the government made these classifications more applicable to most Americans. In an increasingly diverse society, last century’s racial classifications risk becoming obsolete as people identify themselves in different ways.

Ida Abhari is a freshman majoring in philosophy, politics and law.

All notions of racial superiority rest on the myth that the most “superior” of the alleged “races” must be “pure” and unmixed with the other “races.” Destroy the myth that “white” equals “pure” (multiracial whiteness) and you have effectively destroyed racism:

How is it useful to divide people into racial groups? It sets up an artificial competition between groups for limited government provided assistance when our nation was built to respect the rights of individuals.

I must commend the author on an extremely well written article. The author makes many good points and it truly can be argued whether or not the surveying is properly defined. It really comes down to what is the purpose of the survey discussed here. I must believe that the survey preparers were and still are overwhelmed with the possible number of boxes and the confusion it may generate with a good portion of the population. I surmise that they decided to categorize at major group levels for simplicity, perhaps over-simplified. This was likely suffice for their needs based on budget constraints or driven by other factors. More importantly, it is the relationships that we the United States carry with the rest of the world. The relationships built via our State Department is where it really counts given your concerns. This area of Government is where they spend the time to learn about the differences between our customs, religions, beliefs, etc across the globe. You may want to take a look at the State Dept website if you haven’t already and truly examine the efforts taken to work with the masses. It is very hard work and requires those most capable to do it. I would want to educate and ensure people are cognizant and not boxed in to believe the entire US Government thinks the same way. Lastly, we must remember both sides are important, which is what makes this country so great.