I Reckon: West Virginia’s leaders are abandoning West Virginians

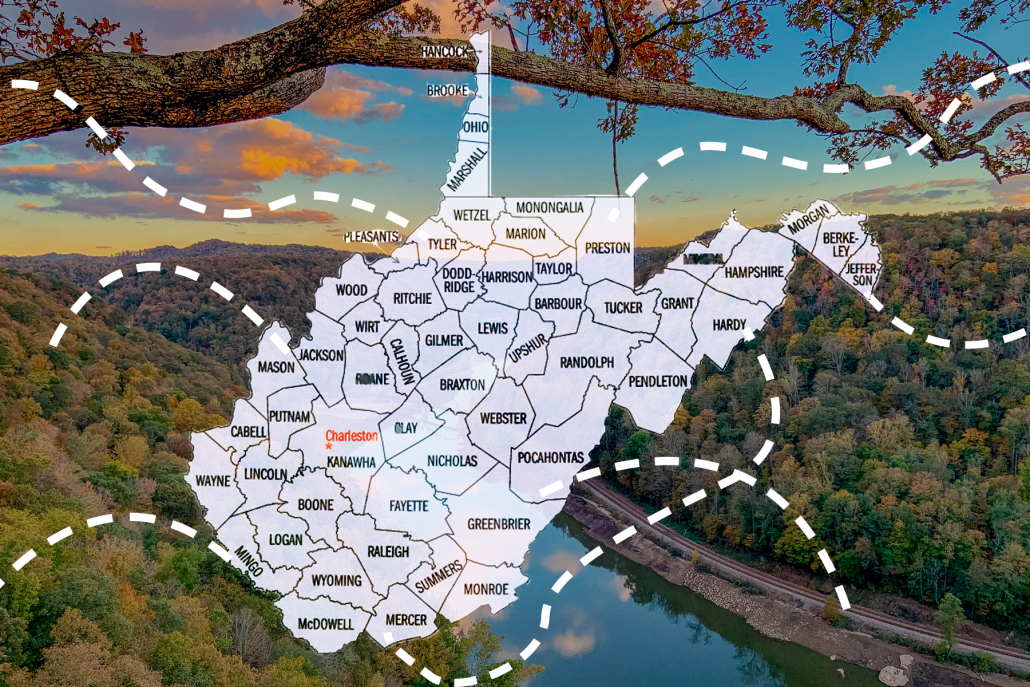

There is perhaps no state more neglected than West Virginia. The place John Denver once dubbed “almost heaven” in “Take Me Home, Country Roads” has a significant political history and is highly dependent on coal and mineral production. Now, after being lied to by former President Donald Trump who promised to bring back coal and soon-to-be neglected again by the current President’s party, West Virginia finds itself seemingly in the same old situation.

However, recent data from the 2020 United States Census warns that West Virginia could face something worse than political neglect and stagnation as a population crisis looms on its rugged horizon. West Virginian leaders’ most recent attempt to solve the problem would not only be detrimental to folks already struggling to stay, but it could also exacerbate the mass exodus out of the Mountain State.

According to the most recent U.S. Census data, West Virginia has lost more residents than any other state. The population declined 3.3% over the past 10 years, which means that roughly 60,000 West Virginians have fled. Many have left through no fault of their own: Populations decreased in counties where coal mines have shuttered, despite the promises of political leaders from the state and federal level to revive the heart of coal country.

Others have left because manufacturing jobs moved their operations overseas. As a consequence of its catastrophic population loss, the state will be losing a congressional seat, another kick in the head for a state already plagued by the specter of the opioid and HIV crises and exploitation by outside corporations.

Political leaders in West Virginia are responding to the population dip with a program called Ascend WV, a collaboration between the state’s Department of Tourism, the state’s Department of Economic Development and West Virginia University. It is bankrolled by West Virginian and former Intuit CEO Brad D. Smith with a hefty $25 million donation. With that boost of funds, Ascend WV’s website promises $12,000 in cash to remote workers willing to relocate to the state, as well as a year of free outdoor activities and access to coworking spaces. Approximately 7,500 people have applied to take one of the 50 spots in the program.

Elected officials in West Virginia, slow to realize that the coal industry was already a foot in the grave years ago, are obviously in a pinch to diversify their economy — and fast. Their solution to woo remote workers to the state means attracting those in the tech industry. Remote workers bring in big money themselves: Payscale’s research on new salary data found that remote workers earn roughly 8.3% more than non-remote workers with the same experience doing the same job.

On the surface, incentivizing high earners to come to the Mountain State to spend and bolster local economies sounds enticing for a state struggling to get itself on track. And yet, I just can’t help but think that these remote workers are harbingers of something worse: a second Silicon Valley.

Low and middle-income folks from Silicon Valley will surely understand what I’m talking about. To its credit, Silicon Valley has been an engine of creativity and innovation, driving the tech industry to new heights. Yet, so many folks who have lived in the region for decades are fleeing the area, if not the state, simply because they can’t afford to live there any longer as the prices of homes and the cost of living soar. It is a mass exodus spurred by the introduction of high-earning tech and remote workers, and it is my greatest fear that West Virginians will face the same fate as fleeing Californians if Ascend WV gains more traction.

This fear isn’t rooted in some feverish prophecy that warns that everything the tech industry touches is ruined. It is more rooted in the fear that state leaders are courting non-West Virginians while doing absolutely nothing to address the concerns of those currently living in the state.

Danielle Walker, a Democrat in the West Virginia House of Delegates, warns that the perks offered to remote workers by Ascend WV would essentially create a form of redlining in Morgantown, a city that she represents as well as one of the sites promoted by Ascend WV. Without offering a program that would offset the effects of redlining, West Virginia’s elected leaders cease to do their duty and serve their constituents.

Proponents of Ascend WV usually deflect concerns like those from Danielle Walker, arguing that the program’s remote workers won’t be competing for local jobs because they’d be working online or at home. Proponents also say that these remote workers would also be supporting local businesses and economies. However, remote workers won’t need to compete for local jobs, especially since such jobs for blue-collar workers are already disappearing.

And as optimistic as state legislators are about the altruism of the remote and tech industry, West Virginians deserve more than short-sighted transactional philanthropy. They deserve direct aid and support from the state and its elected officials. They deserve more investment in the education of their children, healthcare and infrastructure. If not, the current mass exodus out of the Mountain State will never end.

Quynh Anh Nguyen is a sophomore writing about current political events as an Asian-American Southerner and California transplant.