Separate buses are not equal

When I tell people that I take public transportation, I am often met with worried stares. After all, urban centers have a pretty bad reputation when it comes to sexual harassment. I’ve bought into the warnings I’ve received about riding at night and having pepper spray on hand. If Los Angeles had introduced a women-only train car, I would’ve spent way more time in the city and much less time on public transportation worried about the length of my skirt.

Unfortunately, my fear is far from irrational. In metropolitan cities around the globe, harassment is a serious issue for female commuters. A 2014 Thomas Reuters Foundation poll revealed that 32 percent of women in London have experienced verbal harassment on public transportation. The situation is even worse in Latin American cities, where six out of 10 women have reported physical assault on public transit. Given all this abuse, it is no wonder that many countries — including Japan, Mexico and Brazil — have introduced women-only train cars in an effort to curb the abuse.

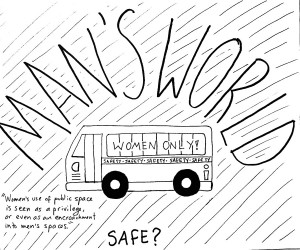

Kathmandu is the latest city to adopt gender-segregated public transport. The city launched a women-only minibus service this month, providing women commuters with a haven from verbal and physical abuse. This new initiative is due in part to a recent World Bank survey revealing that 25 percent of young Nepalese women have experienced sexual harassment on public transportation. Bearing these global statistics in mind, women-only transit seems like a rational response. This type of response, however, can only go so far; shielding women in this way shifts the blame to victims and will only further exclude women from public spaces.

In a Jan. 7 article for The Guardian, columnist Jessica Valenti responds to Kathmandu’s initiative, pointing out that “gender-segregated public transport can only help women for the length of one commute.” Valenti goes on to note that “sexual harassment isn’t limited to confined spaces and can’t be eliminated by buying an automobile, even if you can afford one.” It is unrealistic to segregate every aspect of public life, so this cannot possibly be the answer to ending this epidemic. After all, public transport is only one setting for sexual harassment, and some degree of male interaction is all but inevitable.

Moreover, this segregation further removes women from the public sphere, fueling the idea that these spaces belong to men. Global Voices discussed the continuing harassment of women on Delhi’s Metro system, despite efforts to designate women-only seats. Statistics revealed the futility of gender segregation, and the seating situation itself reeks of an underlying gender hierarchy. Indeed, the four women-only seats per train car are lumped together with the four seats reserved for the disabled and elderly, as if being female is a handicap. The article includes one blogger’s observation that “women’s use of public spaces is seen as a privilege, or even as an encroachment into men’s spaces.”

Of course, this is only one country, but male entitlement to public spaces is no isolated cultural phenomenon. One look at the Tumblr “Men Taking Up Too Much Space on the Train” is enough to demonstrate the prevalence of “public assertions of privilege” in Europe and the United States. The Huffington Post points out, “the men photographed … aren’t doing anything malicious, but it’s an interesting visual representation of the way that men feel totally empowered to take up a lot of public space — and women often do not.”

With all these displays of male privilege making headlines, the fact that women are the main users of public transport in most urban centers comes as quite a surprise. The United Nations Women website explains this phenomenon, pointing out that women and girls are more likely to move through cities in “criss-crosses and zigzags” in order to accomplish their duties as primary caregivers and members of the labor force. This misperception is a huge part of the problem; no government can adequately cater to female riders if they’re wrongly viewed as a handicapped minority. Moreover, women should not shoulder the blame for this epidemic, especially if victimized female riders outnumber the perpetrators. Women should not need to adjust their transportation routine to accommodate assailants, and they should not face victim-blaming if they reject available segregated transportation. Society needs to view women-only transit for what it is — a temporary fix, one more “You should have …” when the next victim speaks out.

Jennifer Frazin is a sophomore majoring in English and theatre. Her column, “Not That Kind of Girl,” runs Wednesdays.