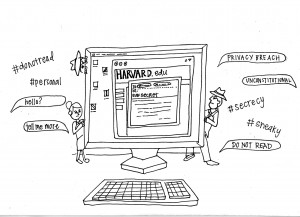

Do colleges have the right to search faculty emails?

Institutions of higher education should be allowed to monitor the potentially illegal activities of its students and staff.

In this age of technology, questions of security and privacy are in constant motion. Unfortunately, the Internet is far too vast of a wasteland to truly enforce and guarantee full privacy — and one should not expect such privacy in the first place.

This issue was clearly relevant during a cheating scandal that took place at Harvard College in 2012. Last September, the prestigious school of higher education revealed that a massive plagiarism scandal had taken place the semester before. According to CNN, more than 100 students in “Government 1310: Introduction to Congress” were asked to withdraw from the university for a period of time, suspended or faced other disciplinary actions from the university after faculty noticed similarities between many take-home final exams.

The scandal was supposed to have wrapped up with that. But this past Monday, Deans Michael D. Smith and Evelynn M. Hammonds released a statement saying that the college’s IT department had been instructed to search through the email accounts of resident deans in order to see if anyone had disclosed a confidential document regarding the cheating scandal.

According to the statement, “No one’s e-mails were opened and the contents of no one’s e-mails were searched by human or machine.”

Yes, an email search of any kind could be considered troubling to some. Yet many do not realize the implications of possible leaks of confidential information in any sort of carefully run organization.

If a resident dean were found to be at fault, then the college would be able to rid itself of a faculty member who would not be able to follow the policies the college wants to maintain. But since the search ended in administrators discovering that a resident dean had merely forwarded the confidential document unintentionally, many are up in arms over the situation.

The truth of the matter is this: Harvard has every right to search the email accounts of its faculty and students since these account addresses end with an “@harvard.edu.” These accounts are owned by Harvard University and given to its faculty and students as a privilege, not a right.

“Why not tell people you are reading their e-mail? Would it not be the honorable thing to do?” Harry Lewis, the Gordon McKay Professor of Computer Science and the Director of Undergraduate Studies in Computer Science at the university, posted on his blog.

In order to catch the possible culprit, however, secrecy was key. What was to stop a resident dean from deleting guilty emails from his or her account once he or she got wind of the search?

School email accounts can be used for personal purposes, and many are. But in the end, these accounts are owned by the institution that bestowed them upon its students and faculty.

If one feels that their rights have been infringed upon, then our expectations are widely delusional.

Sheridan Watson is a junior majoring in critical studies. She is also the Editorial Director of the Daily Trojan.

Searching through active personal university email accounts is an extreme breach of ethics and trust.

On the extent of the breach, the fact that Harvard stopped at the subject line is still frightening. This callous disregard for privacy shows the extent to which Harvard will monitor its own administrators to investigate an internal problem, according to CNN. It also begs another question: If Harvard had not found the leak based on the search of the email subject lines, would they have actually read the contents of each email? At what point was Harvard going to engage in legal and ethical investigative techniques and stop violating the privacy of its faculty?

The fact that Harvard did this to administrators is also frightening for a few other reasons. Foremost, if this is how Harvard treats the administrative faculty, then how does Harvard treat other professors? Lecturers without tenure? Staff? Students? If Harvard is willing to scan the email of its best and brightest faculty, then no email account at Harvard is safe.

This is a dangerous precedent for the school to set. Everyone pretty much wants their privacy, and Harvard’s actions are a severe breach of trust. If a school gives faculty and administrators job security through mutual trust, they can be much more effective instructors and leaders. But if professors have to start worrying about what they write in an email, then the concept of tenure is moot.

With this breach in privacy, however, faculty could feel like they have to worry about what they are saying, to whom they are speaking and how they are saying it because the administration is willing to read their emails to single them out for punishment. In this hypothetical situation, Harvard becomes unable to function as a legitimate educational institution.

Harvard should have never read the emails of deans, nor should Harvard ever endeavor to engage in such activity ever again. Hopefully Harvard can learn from its mistakes and become a respected representative of American higher education.

Dan Morgan-Russell is a freshman majoring in international relations.

Yes.