Microfinancing helps with crisis

Kiva announced last week that it has passed the $400 million milestone in microloans, a landmark achievement for an organization that relies on private donors to finance loans as small as $25 in developing countries.

This field, known as “microfinance,” has recently become immensely popular, inspiring similar movements across the nation. In 2009, New York Times journalist Nicholas Kristof famously said, “Microcredit is undoubtedly the most visible innovation in anti-poverty policy in the last half century.”

For a business student, especially, it’s easy to want to believe that typically capitalistic fields like banking and finance can cause a positive social impact. But unless combined with other efforts, microfinance is unlikely to enact sustainable progress for those in developing countries.

The field of microfinance, which has benefitted more than 500 million people, has gained considerable popularity since Muhammad Yunus won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2006 for creating Grameen Bank, Forbes reported. Organizations such as Kiva, Accion and Grameen Bank have allowed people to take out small loans to support their businesses, even in areas where financial services are difficult to obtain.

The impact has been staggering. Grameen Bank alone is reported to have served seven million of the world’s poorest families, according to the Grameen Foundation website.

“Many see microcredit as much more than a financial instrument: it has been suggested that it has the potential to be entirely transformative,” Kristof wrote.

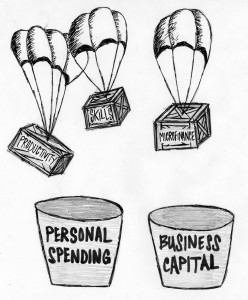

Yet, it wasn’t long until the backlash against microfinance began. Many questioned the use of the microfunds by lenders in rural areas. “Nine out of 10 microfinance loans are for consumption rather than to start or grow an enterprise,” said Hugh Sinclair, author of Confessions of a Microfinance Heretic: How Microlending Lost Its Way and Betrayed the Poor.

Although the statistic is shocking, the idea that families in poverty are likely to spend financial loans on basic survival resources instead of on burgeoning business is understandable. Nonetheless, the spending of microfinance funding on consumption goods rather than on businesses is contradictory to the message of the industry.

“There is a lot of misinformation and misunderstanding about what really is going on in microfinance,” Sinclair notes. “On the one hand, we hear of rumors of exploitation of the poor. On the other hand, good, well-meaning Americans and Europeans are donating and investing their money in this sector without really knowing what’s happening.”

In fact, reports of people in poverty caught in a circle of serious debt, as well as of people unable to repay debts with high interest rates, has drawn attention to the limitations of microfinance in a for-profit industry. While proponents of microfinance continued to defend the field, the criticism has become more and more severe. “On current evidence, the best estimate of the average impact of microcredit on the poverty of clients is zero,” said David Roodman, a fellow at the Center for Global Development.

Though it might be disheartening to hear, microfinance is most likely not the silver bullet to ending poverty. The underlying causes behind poverty are complex and based on a number of factors, not just financial stability or access to capital.

The potential of microfinance to make a difference can be severely inhibited by problems of organizational corruption, unsustainable accumulation of debt, high interest rates and other issues. Though microfinance might be a step in the right direction because it empowers people to start businesses, a multi-disciplinary approach to poverty reduction is a much better course of action.

Despite all these factors, the future of microfinance is bright. “World leaders should come together again to provide the powerful and visionary leadership to help steer microcredit back on course,” said Yunus, arguably the world’s leader in microfinance.

With the right insight and protection of microfinance institutions, such progress might be possible. They might not be the answer for impoverished nations, but socially responsible microfinance organizations like Kiva clearly have the potential to make a positive impact.

Payal Mukerji is a junior majoring in business administration. Her column “Risky Business” runs Tuesdays.

Kiva loans are not for $25, that is the amount you, the generous lender, can send to Kiva and then on-lend. The loans on the front page of Kiva today range from $1000 to $5000.

Suggesting that microfinance has “benefitted” more than 500 million is a loaded term, implying that it has had a positive impact. It has perhaps “reached” this many, but anyone with a credit card will confirm that simply spending money and paying your bill at the end of the month doesn’t necessarily make you any better off. The microfinance community is quick to point out the number of people “reached” and the % that repaid a loan. The evidence of it actually helping is largely absent. You cite Roodman’s legendary “zero” quote regarding the average impact such loans have on poverty – he is not alone is making this claim – see Chang, Stewart, Harper, Duvendack, Bateman etc. The evidence that microfinance eradicates poverty is entirely lacking other than courtesy of a few isolated claims supported by photos of women with goats, made by people whose salaries depend on microfinance.

Have you ever wondered how it is that Kiva are able to provide photos, loan details, little heart-warming stories about their borrowers, and yet cannot even state the interest rate of the loan? Think about this carefully. That Kiva even exists says more about the integrity of the US regulator than the effectiveness of microfinance.

You mentioned some of the classic criticisms of microfinance, but you missed the main concern. The vast majority of capital is chanelled through a handful of intermediary organisations such as Kiva, and the vast majority of information flowing back from the field to the ultimate investors is channelled through the very same people. These people earn often substantial returns for this churn. There is a catastrophic conflict of interest in the process. Economists call this the “principal-agent problem”. To remove the huge temptation to exaggerate the miraculous properties of microfinance genuine transparency and regulation is required. Very little of either exists, either in the developing countries where most microfinance takes place or in the developed countries where the funds largely originate. Until we resolve this problem don’t expect much improvement. And those who will most fiercely resist such regulation, or opt for a feeble self-regulatory body such as the Smart Campaign, will be precisely those with the most to gain from the current lack of any meaningful scrutiny over microfinance in practice.

Sheep need to be protected, and wolves are not good shephards. The microfinance sector is dominated by wolves. This is one of the main reasons why the results have been so poor to date. Controlling the wolves is the most pressing challenge we face if we wish to contribute to poverty eradication using microfinance.