Politics needs nonpartisanship

I am not an Independent. On the vast majority of issues, I find myself squarely to the left of center on the political spectrum. I registered to vote as a nonpartisan. I did this because being nonpartisan does not make one independent on issues of policy — it makes one independent on issues of politics.

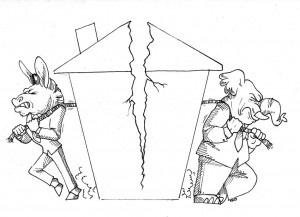

Victoria Cuthbertson | Daily Trojan

There is a difference. Such a distinction might seem small. But it makes us a house divided. And as President Lincoln warned, a house divided cannot stand.

A partisan is a staunch supporter and defender of a political party. In most other countries that have smartly strayed away from the two-party system of the United States, the term carries a horrendously negative connotation. To be partisan in the United Kingdom, for example, is to defend the party at all costs. It is to deny the ability of the opposition to enact change or offer different solutions to the challenges before the government. Partisans refuse to admit that their compatriots on the other side of the aisle might be right in some instances. Sound familiar?

The United States Congress is a house divided because we deal with issues of policy with the tools of politics. The 112th Congress had the fifth-highest number of vote counts since 1947, but passed fewer bills since any Congress since then, according to the Huffington Post. What does this tell us?

Often, debates on the Hill and State capitols are rife with extra-legislative motivations and are counterproductive to the duty of our government, which is to represent the interests of the majority. Not the rich. Not the powerful. Not the well connected. The majority.

How do we go about putting policy on a higher pedestal than politics? It begins by recognizing that the answer is not to be bipartisan. To strive for bipartisanship as the epitome of political engagement is to foolishly believe that it is possible for a group of very different people with very different ideals to somehow not choose differently on most issues. The ideal outcome is not to increase the times we agree, but rather to make the times that we disagree more productive.

The philosopher Hagel posited that intellectual advancement is facilitated through the dialectic: That is, the combination of the thesis and the antithesis. In other words, Hagel believed that taking two ideas that were in opposition to each other and reconciling them to form a solution created a synthesis better than either of them alone.

Thus, an essential starting point for bettering our politics is to understand that disagreement should be productive. The status quo of legislating is that our representatives are unwilling to reconcile disagreements in the productive fashion that Hagel envisioned. Instead, our disagreements become what Winston Churchill affectionately referred to as a “sausage factory,” where one sees and smells a lot of nasty things that induce wincing.

The next step in the process is to understand that to be non-partisan is not to be bipartisan. Bipartisanship is the rosy euphemism bestowed upon miraculous agreements between the Republicans and the Democrats. To be nonpartisan means that one refuses to engage in struggles motivated by party allegiance, special interests and personal gain, and instead utilizes disagreements to incorporate the needs of the opposition while still preserving one’s initial intent.

The problem with bipartisanship is that it mistakenly believes agreement to be a better form of politics than productive disagreement. This is wrong. Where bipartisanship would happily make purple out of red and blue, nonpartisanship would produce a marble cake that preserves the best aspects of both colors.

It is appropriate to question the above logic in instances where a clear majority is present. Why care about the opposition when their support is not needed? Several reasons. First, in most systems with more than two parties, a coalition is needed to achieve a majority with voting power. Second, in the two party system, a victory along party lines sows the seeds of discontent for political struggles later on. Furthermore, the Senate rule requiring 60 votes to end a debate means that no party can have an unbreakable majority (it has happened twice in 30 years).

By focusing on domestic political disputes through the lens of nonpartisanship, progress can be made. It is a rare day when both parties can initially come together in support of a policy, but it is an even rarer day when one party truly has a monopoly on being right. The sooner that politicians recognize this, the sooner they can get back to doing what they were elected to do.

Nathaniel Haas is a sophomore majoring in economics and political science. His column, “A House Divided,” runs Thursdays.

Follow Nathaniel on Twitter @Haas4Prez2036